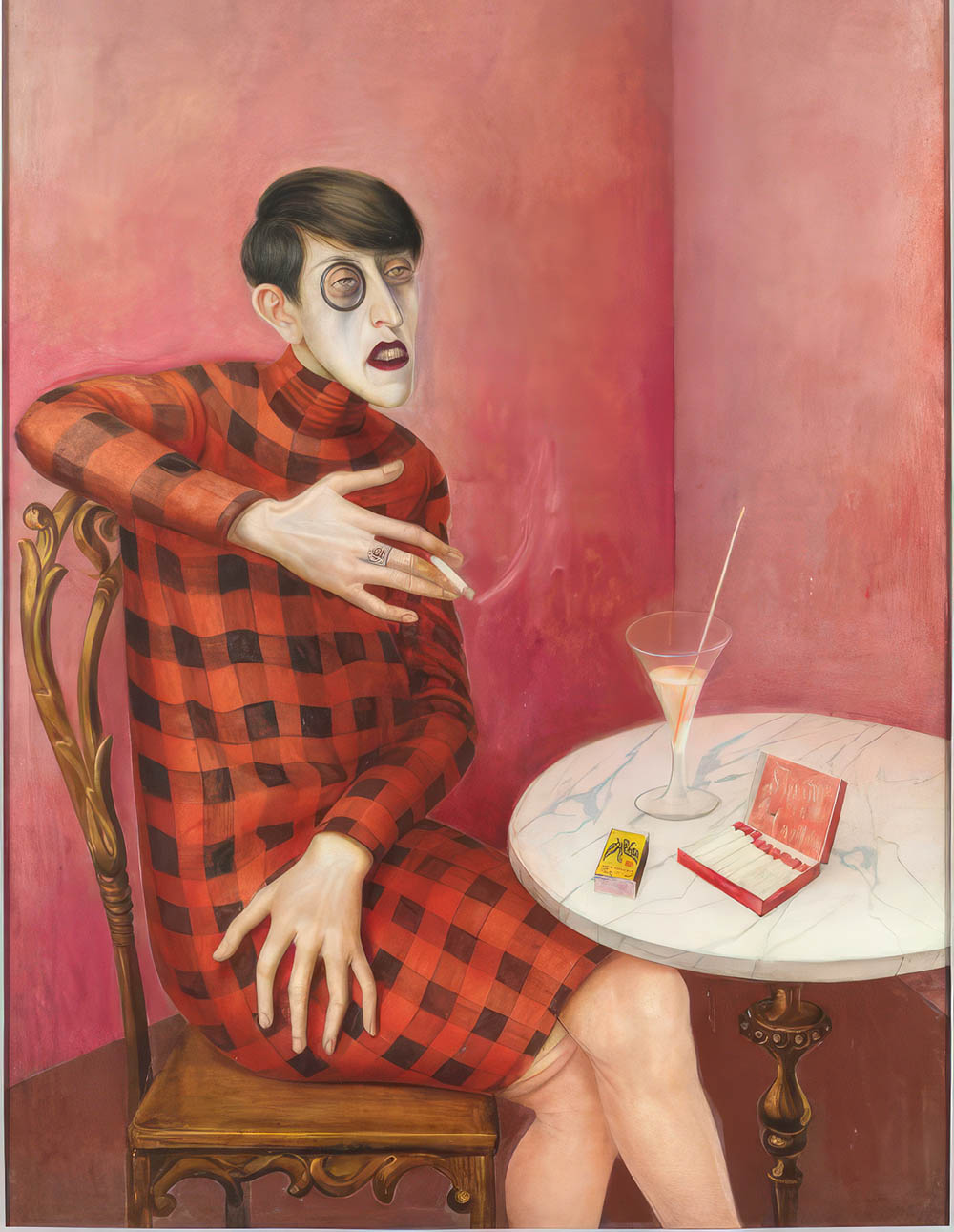

The Meaning of Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden

In 1926, in a smoky Berlin café, Otto Dix, a master of Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), locked eyes with a woman who would soon become immortalized in one of the most iconic portraits of the Weimar Republic. That woman was Sylvia von Harden: journalist, poet, and embodiment of the new German woman. With her cropped bob, monocle, cigarette, and aloof air, she was the quintessential symbol of a shifting world where femininity, intellect, and rebellion were being redefined. The painting Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden is more than a likeness; it is a psychological, social, and cultural document frozen in oil on canvas.

Who Was Sylvia von Harden?

Sylvia von Harden was the pen name of Sylvia von Halle, a German journalist and poet associated with Berlin’s literary avant-garde during the Weimar period. She was known for her incisive intellect, nonconformity, and bohemian lifestyle. Von Harden, like many of her contemporaries, embraced the “Neue Frau” (New Woman) identity, a movement among women who rejected traditional roles in favor of independence, intellectual pursuits, and visual modernity.

To Dix, she was a muse not in the romantic sense, but in the ideological one. He once recalled:

“I must paint you! I simply must! You are representative of an entire epoch, an epoch that is falling apart.”

It was not her beauty but her persona, her radical modernity, that made her an icon worthy of depiction.

The Moment of Creation: Painting Sylvia von Harden

Otto Dix painted the portrait in 1926, during a volatile period in Germany’s history. The aftermath of World War I had left the country in economic and social disarray. Weimar Berlin was both a playground of decadence and a ground zero of artistic experimentation. Dix, a veteran of the war, had turned to art not for escapism but to dissect the trauma, instability, and contradictions of the times.

The portrait was done in Dix’s characteristic style of Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), which emphasized unsentimental, hyper-realistic, and often harsh depictions of contemporary life. With this piece, Dix employed oil and tempera on wood panel, melding classical techniques with modern themes. The color palette is cold, dominated by reds, browns, and grays, creating a sterile atmosphere that echoes the alienation of modern existence.

Sylvia sits at a café table, surrounded by objects, cigarette, matchbox, cocktail, handbag, that define her but also isolate her. Her elongated fingers, red lipstick, short hair, and monocle do not seduce but deflect. The composition and execution signal a woman apart: untouchable, indifferent, perhaps even weary.

What Is Happening in the Painting?

In the portrait, Sylvia von Harden sits alone at a small café table. She is depicted in profile, though her eyes meet ours directly, challenging us. Her left leg is crossed elegantly over the right, and her angular arms rest on the table, one hand lightly grasping a cigarette. Her pose is self-assured but not inviting. She seems simultaneously present and removed.

The space around her is sparse, nearly clinical. There’s a half-full cocktail glass, perhaps a martini, next to a lit match, suggesting a moment mid-smoke. Her lipstick is severe; her eyebrows are plucked and penciled. The background, a red-checkered floor stretching to a dull pink wall, evokes a sense of spatial dislocation, neither cozy nor quite real. There is no one else in the scene. She exists in her own world, one of intellect, solitude, and subtle defiance.

Symbolism in the Portrait

1. The Monocle

The monocle perched in her right eye is perhaps the most jarring detail. Typically associated with aristocratic men, it appears almost absurd on Sylvia. But this is intentional. The monocle becomes a symbol of intellectual scrutiny, androgyny, and defiance. It mocks traditional femininity while asserting authority.

2. The Cigarette and Cocktail

The cigarette, partially smoked, and the cocktail, half-finished, are artifacts of a liberated yet weary culture. They suggest urbanity and detachment, pleasure and decay. These are tools of both sophistication and self-destruction, a dichotomy central to the Weimar zeitgeist.

3. Her Attire and Hair

Her red dress, modest yet modern, and her bobbed hair align her with the New Woman movement. This style signaled independence, sexual liberation, and a rejection of traditional female roles. Yet, Dix paints it all with a clinical precision that removes glamour and imbues everything with existential fatigue.

4. The Setting

The café setting is emblematic of Berlin life, an urban realm where ideas, politics, and decadence mixed. But the isolation in the scene, no crowd, no clamor, turns the lively café into a metaphorical cage. The floor’s perspective leads nowhere. The table, too small for comfort, becomes a stage, and Sylvia its reluctant performer.

What Is the Painting Really About?

At its core, Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden is not just about Sylvia. It is about modernity itself. Otto Dix uses Sylvia as a vessel to explore the alienation, contradictions, and tensions of Weimar-era Germany. This is a portrait of a woman, but also of a cultural moment.

The New Woman

In the 1920s, the “New Woman” emerged as a symbol of progress and anxiety. She worked, smoked, voted, remained unmarried, and rejected conventional domesticity. Sylvia von Harden was such a woman, not only in appearance but in ideology. Dix captures both her freedom and her isolation. She is liberated, yes, but also alone. Her androgynous presentation blurs lines of gender and sexual identity, suggesting that liberation comes with its own burdens.

The Psychological Undercurrent

Dix paints not the inner warmth of the subject but her psychological armor. Sylvia is closed off. Her hands, expressive yet tense, indicate a certain brittleness. Her gaze, direct but cold, resists interpretation. The viewer is not invited in but confronted, judged even. The portrait captures a mind in its own realm, locked in contemplation or perhaps disillusionment.

Decay Beneath the Surface

Dix often painted the rot beneath the surface of society, and here too, there is a hint of existential erosion. The glassy floor, the asymmetrical perspective, the unreal lighting, all subtly suggest that the world around Sylvia is fragile, about to crack. Modern life, for all its promises, seems fraught with instability and spiritual exhaustion.

Artistic Style: Neue Sachlichkeit

Otto Dix was a leading figure of Neue Sachlichkeit, or New Objectivity, a movement that emerged in Germany in the 1920s as a reaction against Expressionism’s emotionalism and abstraction. This new style emphasized realism, detail, and a cool, often cynical detachment.

Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden is a textbook example of the movement. Dix’s hyperrealism, harsh lighting, and emotionally neutral tone strip away sentimentality. The painting becomes not just a portrait, but an x-ray of the age’s psyche. It’s documentary and allegorical at once, offering not just appearance but meaning.

Dix’s training in Renaissance techniques, layering glazes, tempera, and underpainting, enabled him to give his subjects a hyperclarity that almost feels unnatural. His method was slow, methodical, and intentional, every brushstroke imbued with analysis, not emotion.

Where Is the Painting Now?

Today, Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden resides in the Centre Pompidou, Paris. It remains one of Otto Dix’s most recognized works and is frequently exhibited as a key piece in discussions of interwar European art, feminism, and the psychological dimensions of portraiture.

The painting is often juxtaposed with works by contemporaries like George Grosz and Christian Schad, fellow New Objectivity artists, as well as with portraits of women by Expressionists and Surrealists to show the divergence in representing femininity and identity in 20th-century art.

Legacy and Relevance Today

Nearly a century after it was painted, Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden continues to resonate. It is studied not only in art history but also in feminist theory, cultural studies, and psychology. Sylvia von Harden’s image, once considered unfeminine, even grotesque, has become iconic.

Her unapologetic stare has found new meaning in contemporary discourse. In an age still grappling with gender norms, societal roles, and media representation, Sylvia’s image serves as a reminder that the struggle for identity, autonomy, and dignity is both timeless and ever-evolving.

Otto Dix’s work, often grim and clinical, shows us how deeply art can dissect the world around us. In this single painting, he manages to capture not only a woman’s likeness but the zeitgeist of an entire epoch.

Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden by Otto Dix is not merely a portrait, it is a cultural landmark. Painted with piercing realism and laden with symbolism, it captures the fragmented soul of Weimar Germany and the enigmatic identity of the New Woman. Through clinical detail and emotional detachment, Otto Dix presents Sylvia as both icon and individual, muse and mirror.

Her red dress, the monocle, the cocktail glass, each element is a glyph in a visual poem about alienation, independence, and modern life. The painting reminds us that art does not simply represent; it interrogates. And through this interrogation, we are offered not just a glimpse into the past, but a reflection of our own ongoing questions about identity, society, and the cost of freedom.