What Caused the Dancing Plague of 1518

Europe’s Epidemic of Unstoppable Motion

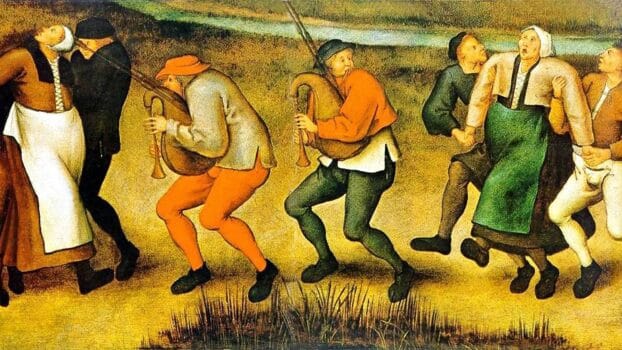

Strasbourg, July 1518. The sun blazed over the cobbled streets as townsfolk went about their lives in the shadow of a crumbling Holy Roman Empire, struggling harvests, and looming war. Nothing seemed extraordinary that summer morning, until one woman began to dance.

Her name was Frau Troffea, and her feet wouldn’t stop moving.

The Woman Who Couldn’t Stop

It began innocently, or so the chronicles say. Frau Troffea stepped into the middle of the street in Strasbourg (modern-day France) and began to dance. There was no music. No festivities. No wedding or celebration. Just her jerking, rhythmic movements, odd and unsettling. Her face, witnesses claimed, was not joyous but strained. Her body contorted and twisted as though caught between pleasure and pain.

At first, neighbors laughed. Then they watched. Then they panicked.

By the end of the first day, Frau Troffea had not stopped dancing. She collapsed from exhaustion only to rise again and keep moving, as if possessed. Within a week, over 30 others had joined her, men, women, even children, caught in a relentless compulsion to dance. By the month’s end, the number of dancers reached a staggering 400.

People danced in the streets day and night, heedless of hunger, sleep, or injury. Many collapsed, limbs trembling and swollen, some reportedly foaming at the mouth. According to historical accounts, dozens died from heart attacks, strokes, or sheer exhaustion.

No one could explain what was happening. Was it disease? Madness? Heresy? Or something even darker?

Historians have long debated the origins of this bizarre event. Was the Dancing Plague a real medical condition? A social phenomenon? Or simply a legend that spun out of control?

The most compelling theories fall into three major categories:

1. Ergot Poisoning

One popular explanation involves ergot, a psychoactive mold that grows on damp rye and can induce hallucinations, convulsions, and muscle spasms, similar to symptoms seen in victims of the dancing mania. The same fungus was later implicated in theories around the Salem Witch Trials.

However, critics argue that ergot poisoning tends to cause violent convulsions and delirium, not coordinated, prolonged dancing. Moreover, if tainted bread were to blame, more people would likely have been affected over a broader region.

2. Mass Psychogenic Illness (Mass Hysteria)

This theory suggests that the Dancing Plague was a case of mass psychogenic illness, where extreme stress and societal pressure manifest physically in groups. In 1518, Strasbourg’s residents were suffering: recent famines, disease outbreaks, and religious upheaval had left them desperate and afraid.

In such an environment, one person’s trauma could easily trigger a chain reaction. Frau Troffea’s dance may have acted as a psychological contagion, spreading anxiety like a wildfire in a forest already soaked in fear.

3. Religious Ecstasy or Superstition

Another theory suggests the dancers were experiencing a form of religious trance or spiritual possession. The 16th century was steeped in superstition. Many believed in saints who could both curse and cure. In particular, St. Vitus, patron saint of dancers and epileptics, was thought to have the power to curse people with uncontrollable dancing.

Some believed that those affected were trying to dance themselves into a trance in hopes that St. Vitus would forgive them and grant relief. In this context, dancing was both a punishment and a desperate form of worship.

Could the Dancing Plague Happen Again?

Surprisingly, the Dancing Plague of 1518 wasn’t an isolated incident. Similar outbreaks had occurred throughout medieval Europe, particularly between the 14th and 17th centuries. In 1374, hundreds in Aachen (modern-day Germany) danced uncontrollably through the streets, crying for mercy. In Italy, it was called tarantism, allegedly triggered by the bite of a tarantula.

These occurrences suggest that under the right (or wrong) conditions, high stress, poor nutrition, spiritual fear, mass psychogenic illness can manifest in ways that appear supernatural.

Today, we might not see hundreds of people dancing to death in the street, but mass psychological phenomena still occur. Think of panic-buying during crises, contagious behaviors on social media, or mass fainting spells in schools. While modern science and communication act as buffers, the potential for widespread psychosomatic episodes remains.

So yes, in some form, the “Dancing Plague” could happen again, just not quite as it did in 1518.

How Did It End?

As the plague wore on, authorities in Strasbourg tried everything. At first, doctors encouraged more dancing. They believed the victims were suffering from “hot blood” and that the best cure was to let them dance it out.

They even built a special stage and hired musicians to accompany the dancers, an act of good faith that may have worsened the crisis. More people joined in. Injuries escalated. Deaths followed.

Eventually, realizing that the epidemic wasn’t abating, civic and religious leaders reversed their approach. The afflicted were loaded onto carts and taken away, many to a shrine of St. Vitus in the Vosges Mountains. There, they underwent spiritual rituals: baths in holy water, the sign of the cross painted on their foreheads, and offerings made to the saint.

Slowly, the dancing stopped.

Whether it was the spiritual intervention, the isolation from the town, or simply the breaking of a psychological cycle, the plague came to an end. By late summer, peace returned to Strasbourg’s cobbled streets.

Was the Dancing Plague of 1518 Real?

With its surreal elements, people dancing to death, mass hysteria, spiritual pilgrimages, it’s no wonder that some have questioned whether the Dancing Plague ever happened at all. Could it be a hoax or exaggerated myth?

The evidence, however, suggests otherwise.

Multiple historical sources describe the event, including medical records, council notes, and church writings. The Strasbourg City Council logged its responses. Physicians documented symptoms. Religious leaders debated causes and treatments.

While embellishments are likely, such as the exact number of deaths or the dancers’ supernatural stamina, the core incident appears well-documented. It wasn’t fabricated. The dancing happened.

What remains a mystery is exactly why.

Was There a Cure?

Strictly speaking, there was no “cure” for the Dancing Plague, at least not in the conventional sense. There was no medication, no antidote, no medical protocol. The afflicted had to dance until their bodies gave out or until the psychological grip was broken.

The most effective “treatment,” if one could call it that, was spiritual intervention and removal from the environment. The journey to St. Vitus’s shrine, paired with ritual purification, helped many sufferers recover.

In a broader sense, it was belief itself that became the medicine, belief in a higher power, in forgiveness, in healing. Whether psychological or spiritual, it worked. And that, perhaps, is what mattered most.

Echoes of the Dance

Today, the Dancing Plague of 1518 remains one of the most bizarre and unsettling medical mysteries in history. It’s a chilling reminder of how little we sometimes understand the mind, and how easily fear, faith, and frenzy can intertwine.

In a world that increasingly seeks rational answers, the story of Strasbourg is both alien and familiar. We may not dance ourselves to death anymore, but we still fall prey to waves of collective emotion, panic, joy, outrage, fear.

The dancing has stopped, but the rhythm lingers.

The Legacy of 1518

The Dancing Plague of 1518 wasn’t a single event. It was a symptom, of a time, a people, and a fragile human psyche pushed to its limits. Whether it was ergot, hysteria, spiritual possession, or something stranger still, it serves as a profound lesson in the power of belief, community, and the mind’s mysterious depths.

Was it real? Yes.

Was it a mystery? Absolutely.

Could it happen again?

In some ways, perhaps it already has. image/CP Media Pte Ltd / Alamy)