Decoding the Stars and Stripes: Jasper Johns

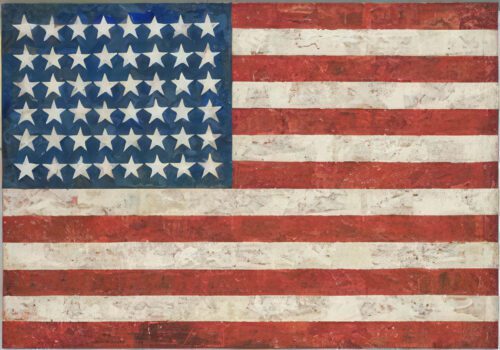

In the pantheon of 20th-century American art, few images are as instantly recognizable yet intellectually provocative as Jasper Johns’ Flag. At first glance, it appears to be a straightforward representation of the American flag, a familiar motif sewn into the national consciousness. But beneath its stars and stripes lies a labyrinth of meaning, rebellion, innovation, and introspection. Painted in 1954–55, Flag is not just a depiction of a national symbol; it is a masterstroke that marked a turning point in postwar American art. Through its complex layers of wax, newspaper, and pigment, Johns challenged prevailing artistic norms, blurred boundaries between abstraction and representation, and redefined what a painting could be.

Who Was Jasper Johns, and Why Did He Paint Flag?

To understand Flag, we must first understand the man behind the brush. Jasper Johns, born in 1930 in Augusta, Georgia, grew up in the South during a period of profound social and political change. He moved to New York City in the early 1950s, where he became a central figure in the post-Abstract Expressionist movement. At that time, Abstract Expressionism, championed by figures like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, dominated the art world. This movement emphasized gestural brushwork, emotional expression, and non-representational forms. Johns, however, found himself disillusioned with its self-seriousness and internal logic.

One night in 1954, Johns claimed he had a dream about the American flag. The next day, he began work on what would become one of the most important paintings of the 20th century. He later explained, “One night I dreamed that I painted a large American flag, and the next morning I got up and I went out and bought the materials to begin it.”

That decision, to paint something as common, as omnipresent, and as emotionally loaded as the American flag, was nothing short of revolutionary.

How Flag Was Created: Wax, Newspaper, and Subversion

Flag was created using a technique known as encaustic, in which pigment is mixed with hot wax and then applied to the surface. This method, rarely used in the modern era, allowed Johns to preserve texture and embedded material while creating a luminous, textured finish. In the case of Flag, Johns layered the surface with newspaper clippings, which can still be partially discerned beneath the wax and pigment. This process was labor-intensive and meticulous, taking weeks to complete.

The use of newspaper was especially significant. These bits of journalistic fragments not only added visual complexity but also tied the piece to contemporary time and place. The headlines and text, though largely obscured, hint at the everyday nature of media and its influence on American identity.

Flag measures approximately 42.5 x 60 inches, a little larger than the standard size of a flag used in official settings. This size further contributes to its uncanny quality: it feels both like a real flag and a painting, yet fully functions as neither.

What Kind of Art Is Flag?

Flag defies simple classification, but it is often associated with Neo-Dada, a movement that emerged as a reaction to the rigid doctrines of modernist abstraction. Neo-Dada artists, like Johns and his contemporaries Robert Rauschenberg and Marcel Duchamp (an earlier influence), blurred the lines between art and everyday life. They used found objects, familiar imagery, and unconventional materials to challenge the distinction between “high” and “low” art.

At the same time, Flag is considered a precursor to Pop Art. Artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein would later explore popular imagery, branding, and consumer culture, but Johns’ use of a widely recognized symbol, the flag, laid the groundwork for that aesthetic shift.

Crucially, Flag walks the tightrope between representation and abstraction. While it is clearly a recognizable flag, Johns’ execution, his brushwork, layering, and texture, forces the viewer to focus on its materiality, its form as a painting, not just what it represents. In this sense, Flag occupies a unique place in art history: it is both a symbol and a subject, both an object of patriotism and a meditation on representation itself.

What Does Flag Represent?

On the surface, Flag depicts the American flag, thirteen red and white stripes and fifty white stars on a blue field. But in Johns’ hands, this symbol becomes destabilized.

Johns once said, “Things the mind already knows” was his subject matter. By choosing a symbol as deeply ingrained in American consciousness as the flag, he invited viewers to question their assumptions. What does it mean to paint a flag? Is it an act of reverence? Subversion? Indifference?

The brilliance of Flag lies in its ambiguity. It doesn’t dictate a specific interpretation. Instead, it holds a mirror to the viewer’s beliefs and biases. For some, it might represent national pride. For others, particularly in the politically charged 1950s during the Cold War and McCarthy era, it might evoke a more critical stance, especially considering the embedded newspaper texts, possibly reflecting on media, war, and propaganda.

The flag also resonates with themes of identity, memory, and perception. Is it a flag or a painting of a flag? If it’s a painting of a flag, can we separate its symbolism from its status as an art object?

Symbolism and Deconstruction: What Is Happening in Flag?

On a formal level, Flag is a meditation on symbols. By reproducing a national emblem with painstaking craft, Johns forces the viewer to pause and reconsider something they usually take for granted. He deconstructs the symbol through material and context.

There’s also an undercurrent of detachment and irony in the work. Unlike the emotional tumult of Abstract Expressionism, Johns’ painting is calm, restrained, and enigmatic. It doesn’t scream, it hums. It invites rather than commands.

Moreover, the decision to paint the American flag in the mid-1950s, during a time of political conformity, anti-communist hysteria, and rigid definitions of patriotism, was a subtle act of defiance. Rather than attacking or glorifying the flag, Johns presented it as an object of contemplation, thereby removing it from its ideological pedestal.

Some scholars suggest that the flag’s fragmentation and layering echo the fractured nature of American identity. The newspaper fragments, traces of the mundane and the political, embedded beneath the surface point to the interplay between public symbols and private lives, between national myths and personal truths.

The Flag as an Object vs. The Flag as a Symbol

Another powerful element of Johns’ Flag is its emphasis on objecthood. He was famously interested in things that are “seen but not looked at.” By painting a flag, Johns made an object we rarely question into a focal point. He didn’t just depict it, he constructed it, layered it, transformed it.

In doing so, Johns collapses the divide between image and object. The flag is no longer something that flutters above a schoolhouse or hangs on a porch; it becomes a tangible surface, textured with wax, imbued with time, and weighted with meaning.

Reception

When Johns first exhibited Flag in 1958 at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York, it caused a sensation. The painting attracted the attention of influential artists and critics, including Alfred H. Barr Jr., the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), who later acquired the piece for the museum’s permanent collection.

Some critics were unsure how to interpret it. Was Johns mocking American ideals? Was he celebrating them? The ambiguity unsettled many, and fascinated others. Over time, Flag came to be seen as a watershed moment in modern art, signaling a departure from Abstract Expressionism and paving the way for the rise of Pop Art, Minimalism, and Conceptual Art.

Johns’ work influenced generations of artists, from Andy Warhol’s repetitive screen prints to Barbara Kruger’s text-and-image critiques. His emphasis on everyday imagery, his use of unconventional materials, and his intellectual rigor made Flag a cornerstone of contemporary art.

Where Is Jasper Johns’ Flag Painting Today?

The original Flag (1954–55), the first and arguably most famous version Johns created, is housed in the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City. It was acquired in 1958 and remains one of the museum’s most iconic holdings.

Johns would go on to produce multiple versions of the Flag over the years, each slightly different in execution and scale. Some are held in private collections, while others are displayed in institutions like the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Art Institute of Chicago.

Today, the painting continues to draw thousands of visitors annually. It remains a powerful, enigmatic icon, still capable of sparking conversation, challenging preconceptions, and offering new meanings in an ever-evolving political landscape.

Why Flag Still Matters

More than 70 years after its creation, Jasper Johns’ Flag remains as relevant and thought-provoking as ever. In an age when symbols are fiercely contested and identity is continuously renegotiated, Johns’ painting reminds us of the power of imagery, and the importance of questioning what we think we already know.

By choosing to paint the American flag, Johns didn’t offer easy answers. Instead, he gave us something better: a space for reflection, for interrogation, and for aesthetic wonder. Flag is a mirror and a window, reflecting who we are, what we believe, and how we see the world.

It challenges us to look beyond the obvious, to find meaning in layers, to see the familiar as strange, and the strange as familiar. In doing so, it remains not just a painting, but a living, breathing question.

And that is what makes Flag a masterpiece.