Art Spiegelman: A Story of Comics and Memory

In the realm of visual storytelling, few names resonate as deeply and lastingly as Art Spiegelman. His art isn’t confined to galleries or auction houses, it’s imprinted in the collective memory of generations who discovered that comics could carry the weight of history, trauma, and cultural critique. A creator, provocateur, and historian in his own right, Spiegelman didn’t just draw; he deconstructed narratives, peeled back the layers of time, and reshaped how we view comics as an art form. But what exactly is the nature of his art, how much does it cost, and what makes it so enduringly significant?

Born Itzhak Avraham ben Zeev Spiegelman in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1948, Art Spiegelman moved to the United States with his Holocaust-survivor parents at a young age. The trauma and history his family carried would later form the bedrock of his most famous work, but his journey into art began like many American boys of his era: through comic books.

From early on, Spiegelman was drawn to the irreverence and raw energy of underground comics. In the 1960s and ’70s, he became a key figure in the underground comix movement, working alongside legends like Robert Crumb. His work in this period was bold, controversial, and always pushing against the boundaries of what comics could be. But it was in the 1980s that Spiegelman began the project that would etch his name into the annals of literary and artistic history.

MAUS: The Masterpiece That Changed Everything

When people think of Art Spiegelman, they almost invariably think of “MAUS”, his groundbreaking two-volume graphic novel. Published in two parts, “Maus I: My Father Bleeds History” (1986) and “Maus II: And Here My Troubles Began” (1991), the work is a memoir, a biography, and a historical account all in one. Using comics as the medium, Spiegelman tells the story of his father, Vladek Spiegelman, a Polish Jew and Holocaust survivor.

In a stroke of symbolic genius, Spiegelman depicted Jews as mice, Germans as cats, Poles as pigs, and Americans as dogs. The anthropomorphic imagery, rather than simplifying the horrors of the Holocaust, heightened the sense of displacement and dehumanization that defined the era.

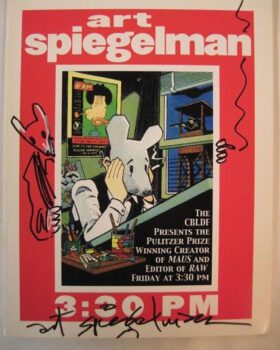

“MAUS” was the first graphic novel to win a Pulitzer Prize (in 1992), signaling a turning point for comics in the literary and academic worlds. It proved that the medium could carry the gravitas of history and trauma, that it could be as potent and artful as any traditional novel or film.

How Does Art Spiegelman Make His Artwork?

Spiegelman’s process is as cerebral as it is visual. His artwork is the result of meticulous research, narrative construction, and draftsmanship. Unlike many modern comic artists who rely heavily on digital tools, Spiegelman works predominantly by hand, valuing the tactile engagement of ink on paper.

He begins with detailed scripts and storyboards, mapping out the emotional cadence and visual composition of each page. From there, he moves to pencil sketches, which he refines obsessively before inking. His panels are designed with a deep understanding of rhythm, where the eye will land, how it will move across the page, how one image transitions into the next.

In “MAUS”, for instance, Spiegelman adopted a stark black-and-white style, both for its simplicity and its emotional weight. There are no flashy colors or digital gradients, just the raw contrast of ink, echoing the moral binaries and existential weight of the Holocaust.

The Art Style of Spiegelman: Expression Meets Realism

Art Spiegelman is best described as a comics formalist, he is deeply invested in the mechanics of the medium. His style borrows from expressionism, surrealism, and modernist illustration, but remains grounded in the storytelling traditions of sequential art.

He does not chase beauty in a traditional sense; rather, his drawings are functional, emotional, and narrative-driven. He uses juxtaposition, repetition, visual metaphors, and unconventional panel structures to immerse the reader in complex emotional states. In “MAUS”, this manifests in haunting symbolism, non-linear time shifts, and visual parallels that deepen the emotional resonance of the story.

In later works, such as “In the Shadow of No Towers” (2004), his style becomes more chaotic and layered, reflecting the psychological trauma of 9/11. Here, he blends early American comic strip references with modern surrealism, layering panels and images to recreate the disorientation of post-attack New York.

Materials and Mediums: What Does He Use?

Spiegelman’s tools are classic but powerful. He often uses Bristol board, India ink, and traditional dip pens or technical pens for inking. His lettering is mostly hand-drawn, which adds a raw authenticity to the page. Unlike modern comics that are heavily colored or digitally enhanced, Spiegelman’s works emphasize the graphic power of black and white.

In “In the Shadow of No Towers”, however, he experimented more with digital collage, color, and mixed media, incorporating elements from newspaper clippings and early comics to mirror the fragmented psyche of a traumatized nation.

How Many Artworks Has Art Spiegelman Created?

While there is no definitive catalog listing every piece Spiegelman has ever drawn, his major body of published work includes dozens of short comics, editorial pieces, cover illustrations (notably for The New Yorker), and a few full-length graphic works.

Beyond “MAUS” and “In the Shadow of No Towers”, Spiegelman has published:

Breakdowns (1977, reissued in 2008), a collection of experimental comic strips.

MetaMaus (2011), an annotated behind-the-scenes look at “MAUS” with interviews and sketches.

Numerous covers for The New Yorker, particularly in the wake of 9/11 and during politically turbulent times.

Collaborative projects with his wife, Françoise Mouly, such as the children’s comic series TOON Books.

If one includes all of his covers, unpublished works, sketchbooks, editorial illustrations, and comics, his total artwork count likely numbers in the hundreds, though only a portion are commercially available or publicly cataloged.

How Much Does Art Spiegelman’s Art Cost?

Unlike many contemporary artists whose original canvases sell for millions, Spiegelman’s work is not primarily sold in the fine art market. His original pages from “MAUS” and other works are rarely available, and when they are, they fetch high prices due to their historical significance.

In private auctions, original pages from “MAUS” have sold for $50,000 to over $100,000, depending on their importance.

Limited edition prints and signed pieces might range from $2,000 to $20,000.

His works for The New Yorker are typically held in the magazine’s archives, but some have appeared in gallery exhibitions and print sales.

That said, Spiegelman is less driven by the commercial art world than many of his contemporaries. He views himself more as a storyteller and commentator than a fine artist. Much of his work is housed in museums, libraries, and university collections rather than private collections.

How Famous Is Art Spiegelman?

In the world of comics, Spiegelman is not just famous, he’s legendary. But his fame extends far beyond comic fandom. He has been:

A Pulitzer Prize winner

A recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship

An inductee into the Will Eisner Hall of Fame

A guest lecturer and fellow at institutions like Columbia University and Harvard

The subject of museum retrospectives, such as the one at the Centre Pompidou in Paris

In 2022, “MAUS” re-entered public discourse when it was banned by a Tennessee school board for its depiction of violence and nudity. Ironically, this only renewed interest in Spiegelman’s work, making “MAUS” a bestseller decades after its original publication.

His cultural impact is on par with literary figures like Toni Morrison or Elie Wiesel, artists who transformed personal and historical trauma into enduring cultural works.

Art Spiegelman Today: A Living Legend

Now in his seventies, Spiegelman remains an active voice in cultural and political discourse. He continues to write, draw, and speak about the evolving role of comics in society, the commodification of trauma, and the political responsibility of artists.

He lives in New York City with his wife, Françoise Mouly, who herself is a pioneering editor and publisher. Together, they have shaped not just the aesthetic of modern comics but their educational and cultural importance.

Through RAW, the avant-garde comics magazine they co-founded in the 1980s, they introduced American readers to global comic artists and elevated the standards of comic storytelling. Spiegelman’s influence, then, is not only in what he created, but in what he nurtured.

Art Spiegelman’s legacy isn’t built on aesthetic flash or mass production. It’s built on depth, risk, honesty, and innovation. He took a medium often dismissed as childish and showed that it could carry the weight of genocide, grief, identity, and memory. He showed that a mouse could speak louder than a historian, and that ink on paper could change how we remember the past.

For those who ask, is comics art?, Spiegelman’s work is the final word: yes, profoundly, unforgettably, yes.