Sacred Stories, Human Emotions: Inside Masaccio’s Art

In history of art, few figures loom as influential yet as enigmatic as Masaccio. Though his career was tragically brief, lasting only about six years, his revolutionary approach to painting changed the trajectory of Western art forever. Masaccio’s pioneering use of perspective, naturalism, and emotional expression marked the true beginning of Renaissance painting, laying the foundation upon which future giants like Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and Raphael would build.

Masaccio (born Tommaso di Ser Giovanni di Mone Cassai, 1401–1428) stands as one of the most important and influential artists in the history of Western art. Though his life was tragically short, his impact on painting was immense and lasting. Masaccio is widely regarded as a founding figure of the Italian Renaissance because he broke decisively from the decorative and symbolic style of medieval art and introduced a new visual language based on realism, scientific perspective, and the truthful depiction of human emotion.

Masaccio was born in the small Tuscan town of San Giovanni Valdarno, near Florence. Little is known about his early life, but he moved to Florence as a young man, where he joined the painters’ guild in 1422. Florence at this time was a center of intellectual, artistic, and scientific innovation. Thinkers such as Brunelleschi and Donatello were redefining architecture and sculpture through mathematical proportion and classical inspiration. Masaccio absorbed these ideas and applied them to painting with unprecedented boldness.

Before Masaccio, painting in Italy was dominated by the International Gothic style. Figures appeared elegant but flat, set against gold backgrounds with little sense of real space. Masaccio rejected this approach. He painted solid, weighty human bodies that occupied believable three-dimensional environments. His figures cast shadows, stand firmly on the ground, and express genuine psychological depth. This radical realism made his work shocking to contemporaries and foundational for future generations.

One of Masaccio’s earliest surviving works, The Madonna and Child with St. Anne (c. 1424), already demonstrates his innovation. The Virgin Mary is not an idealized, floating figure but a monumental, grounded presence. Her body has mass, her face shows quiet seriousness, and the Christ Child appears as a real infant rather than a symbolic miniature adult. The painting marks a clear departure from Gothic delicacy toward Renaissance naturalism.

Masaccio’s most influential achievement is undoubtedly the fresco cycle in the Brancacci Chapel at Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence, painted between 1425 and 1427 in collaboration with Masolino da Panicale. These frescoes depict scenes from the life of Saint Peter and are considered a turning point in the history of painting. In works such as The Tribute Money, Masaccio used linear perspective to organize space with mathematical precision. Architecture and landscape recede convincingly into the distance, guiding the viewer’s eye and creating a coherent visual world.

The Tribute Money also reveals Masaccio’s narrative genius. The same figure of Saint Peter appears three times within a single scene, each moment unified by consistent lighting and spatial logic. The apostles are portrayed as ordinary men, their faces marked by confusion, concern, and authority. Light falls from a single, consistent source, modeling the figures as if they were sculptures. This integration of perspective, light, anatomy, and emotion was revolutionary.

Another masterpiece from the Brancacci Chapel, The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, is one of the most emotionally powerful images of the early Renaissance. Adam and Eve are shown nude, devastated by shame and grief as they are cast out of paradise. Eve’s anguished cry and Adam’s bowed head convey raw human suffering. Unlike earlier representations, there is no attempt to beautify or soften their pain. Masaccio’s honesty gave sacred stories a new psychological intensity, making them more relatable and profound.

Masaccio’s use of perspective reached its peak in The Holy Trinity fresco (c. 1427–1428) in Santa Maria Novella. This work is a landmark in the history of illusionistic space. Using precise linear perspective, Masaccio created the illusion of a chapel receding into the wall. The architectural setting is mathematically constructed, reflecting the influence of Brunelleschi. Below the divine scene, a skeleton lies in a tomb with an inscription reminding viewers of mortality. The fresco unites theology, mathematics, and humanist philosophy into a single, coherent visual statement.

Despite his brilliance, Masaccio died suddenly in 1428 at the age of just 26 or 27, possibly while in Rome. The cause of his death remains unknown. His early death cut short a career that might have transformed art even further, yet his existing works were enough to secure his legacy. Later masters such as Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and Raphael studied his frescoes closely, learning from his use of anatomy, perspective, and expressive realism.

Historically, Masaccio represents a decisive break between medieval and modern art. He treated painting as a rational, intellectual discipline grounded in observation, mathematics, and human experience. His figures inhabit a world governed by the same physical laws as the viewer’s own, making sacred stories feel immediate and real. This shift reflected the broader Renaissance movement toward humanism and the rediscovery of classical knowledge.

What Is Masaccio Known For

Born as Tommaso di Ser Giovanni di Simone in San Giovanni Valdarno, near Florence, on December 21, 1401, Masaccio adopted a nickname that roughly translates to “Big Clumsy Tom”, a moniker likely reflecting his disdain for superficial elegance and social graces. Instead of chasing fame or fortune, Masaccio immersed himself in the world of visual storytelling, pouring his soul into pigments and plaster.

Tragically, Masaccio’s life was cut short when he died under mysterious circumstances in Rome in 1428, at the tender age of 26 or 27. Despite his brief life, the innovations he introduced would ripple through the centuries.

Masaccio emerged during a transformative period in Italian art. The 14th-century Gothic style, characterized by stylized forms and ornamental details, was giving way to a more grounded, human-centered vision of the world. Alongside contemporaries like Filippo Brunelleschi and Donatello, Masaccio embraced humanism, realism, and the revival of Classical antiquity, thereby helping to usher in the Early Renaissance.

Masaccio is celebrated for several groundbreaking contributions:

1. Linear Perspective

Masaccio was one of the first painters to incorporate scientific perspective into his compositions. With help from his friend, the architect Brunelleschi, he mastered the geometric technique of vanishing points and horizon lines to create the illusion of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface.

2. Chiaroscuro (Light and Shadow)

Unlike his predecessors who used flat, decorative color schemes, Masaccio employed chiaroscuro, a technique that uses strong contrasts between light and dark, to give volume and solidity to figures.

3. Naturalism and Emotion

Masaccio’s characters are not ethereal beings but real, breathing individuals. He infused his subjects with human emotion, psychological depth, and physical realism, helping to move away from medieval stylization.

4. Religious Humanism

While deeply spiritual, Masaccio’s work emphasized the human aspect of Biblical stories, showing saints and sinners alike as part of the same emotional and physical world.

Masaccio’s Most Famous Paintings

Despite the brevity of his career, Masaccio’s oeuvre includes several masterpieces that have become icons of Western art. Here are his most significant works:

1. The Tribute Money (c. 1425)

Location: Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence

This fresco narrates a story from the Gospel of Matthew in which Jesus instructs Peter to find a coin in the mouth of a fish to pay the temple tax. The scene is revolutionary in its use of continuous narrative, where different moments in time are depicted within the same frame. The use of perspective draws the viewer into the painted space, while the figures possess real weight and emotion. The fresco is also a political commentary on civic duty and taxation, reflecting the realities of Florence at the time.

2. Expulsion from the Garden of Eden (c. 1425)

Location: Brancacci Chapel, Florence

This emotionally charged fresco shows Adam and Eve being cast out of Paradise. Masaccio’s depiction is raw and unflinching: Adam covers his face in shame, while Eve wails in despair. The anatomical precision and emotional intensity were groundbreaking and deeply moving for contemporary viewers, and remain so today.

3. The Holy Trinity (c. 1427–1428)

Location: Santa Maria Novella, Florence

One of Masaccio’s most celebrated frescoes, The Holy Trinity demonstrates his full command of perspective and architectural illusionism. Painted in a side chapel, the fresco creates the illusion of a receding chapel within the wall. At its apex is God the Father supporting the crucified Christ, with the dove of the Holy Spirit hovering between them. Below are the Virgin Mary, Saint John, and two donors. At the base is a painted tomb with a skeleton and the inscription: “I was what you are; what I am, you will become.” The memento mori theme reminds viewers of mortality and the promise of salvation.

4. The Pisa Altarpiece (Madonna and Child with Saints) (c. 1426)

Location: National Gallery, London (some panels)

Commissioned for the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Pisa, this polyptych is one of Masaccio’s few surviving panel paintings. The Madonna and Child Enthroned reflects Masaccio’s evolving style, with a naturalistic rendering of space and weighty, expressive figures.

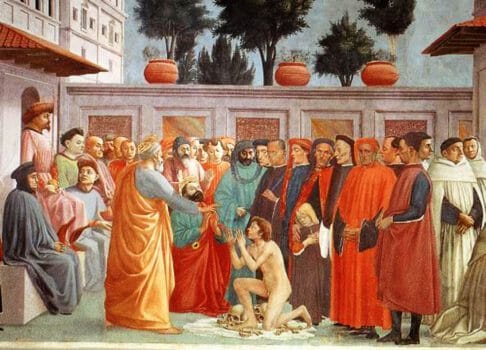

5. Saint Peter Baptizing the Neophytes (c. 1425)

Location: Brancacci Chapel, Florence

This fresco captures the moment Saint Peter baptizes new Christian converts. The attention to water dripping from the neophyte’s head, the chill of the figures shivering in the background, and the emotional gravity all testify to Masaccio’s commitment to realism.

How Many Paintings Did Masaccio Create?

Masaccio’s career was short, and only a handful of works are securely attributed to him, some art historians count about a dozen paintings and fresco cycles, though there are debates about attribution.

His Brancacci Chapel frescoes, done in collaboration with Masolino, represent the most substantial body of his work. While Masaccio painted parts of the cycle, Masolino and Filippino Lippi later completed others. Masaccio’s contribution, however, stands out for its technical and emotional brilliance.

What Is Masaccio’s Most Expensive Painting?

Since most of Masaccio’s works are frescoes embedded in church walls, they have never been sold, and thus do not have auction prices. However, the panels from the Pisa Altarpiece, which were disassembled and sold off over time, are the closest to market-appreciable artworks.

One of the panels, “The Crucifixion,” was acquired by the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples. Another panel, “The Adoration of the Magi,” is housed in the Staatliche Museen in Berlin. If any of these pieces were hypothetically sold today, their value would be in the tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars, given their historical significance and rarity.

But again, no Masaccio painting has ever been sold in a modern art market, and their true value is considered priceless from a cultural heritage perspective.

Where Are Masaccio’s Paintings Located Today?

Masaccio’s surviving works are scattered across several prominent European museums and churches:

Florence

Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine: Home to “The Tribute Money,” “Expulsion from the Garden of Eden,” and more.

Santa Maria Novella: Hosts The Holy Trinity fresco.

London

The National Gallery: Several panels from the Pisa Altarpiece, including The Virgin and Child, are housed here.

Berlin

Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen: Hosts The Adoration of the Magi from the Pisa Altarpiece.

Naples

Museo di Capodimonte: Holds The Crucifixion panel.

Pisa

Originally commissioned for the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine, though the altarpiece was dismantled and distributed to other locations.

Many of his frescoes are still in situ in Florence and are part of Italy’s national heritage. These frescoes are protected and maintained by art conservators, allowing modern viewers to witness firsthand the beginnings of Renaissance art.

Masaccio’s Legacy: The Father of Renaissance Painting

Masaccio’s influence is difficult to overstate. Though he died young, his innovations laid the groundwork for centuries of Western art. Here’s how his legacy endures:

1. Influence on Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci

Both Michelangelo and Leonardo studied Masaccio’s frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel. Michelangelo in particular was deeply influenced by Masaccio’s anatomical precision and emotional intensity, qualities that would define his own masterpieces like the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

2. Revolution in Perspective and Space

Masaccio was the first to master mathematical perspective in a way that not only created realistic space but also served the narrative. Artists from Piero della Francesca to Raphael built on his innovations.

3. Narrative Realism

He redefined how stories were told through painting, emphasizing emotional resonance, physical presence, and human drama. His characters do not just act, they feel, grieve, hope, and fear.

4. Bridge Between Gothic and Renaissance

Masaccio is often regarded as the first true Renaissance painter. He moved beyond the ornate symbolism of the Gothic tradition and forged a path toward the humanist ideals of the High Renaissance.

5. Modern Art Education

To this day, art students from around the world study Masaccio’s works to understand the principles of form, light, anatomy, and perspective. His paintings are part of the canon of classical training.

Masaccio’s Art Is a Dialogue with Eternity

Masaccio’s life was fleeting, but his impact endures like a stone dropped in still water, its ripples touching every shore of Western art. From the sacred walls of the Brancacci Chapel to the museum halls of London and Berlin, his works speak of a moment in history when art broke free from flat icons and came alive with depth, emotion, and intellect.

He was not merely a talented painter but a revolutionary force. In less than a decade of work, he redefined what painting could achieve. Through his mastery of perspective, light, form, and emotion, he laid the foundation for Renaissance art and permanently altered the course of Western visual culture. His legacy endures as a reminder that even a short life can leave an extraordinary and lasting mark on history.

He painted not just bodies but souls, not just stories but truths. In doing so, Masaccio transformed painting from a decorative craft into a window to human experience.

More than six centuries later, the questions he posed about faith, mortality, and the human condition still echo. And his legacy, as the artist who painted like no one before him, remains as fresh and revolutionary as ever.