What Is Agostino di Duccio Known For

In the sun-dappled towns of 15th-century Italy, where art flourished like vines on Tuscan stone walls, a young sculptor named Agostino di Duccio emerged from the shadows of greater-known Renaissance masters. Though history may not always shine as brightly on his name as it does on Michelangelo or Donatello, Agostino carved his own remarkable path in marble, a path that would etch his legacy in the cathedrals and cloisters of Florence, Rimini, and Perugia.

The Rise of a Renaissance Sculptor

Born in 1418 in Florence, the cradle of the Italian Renaissance, Agostino di Duccio’s early life unfolded amid artistic revolution. The son of a relatively obscure Florentine family, he was swept into the orbit of the city’s thriving artistic scene. Scholars believe he may have apprenticed under Luca della Robbia, one of Florence’s revered sculptors and innovators in terracotta reliefs. Others speculate he studied the works of Donatello, absorbing lessons in form, emotion, and sacred storytelling through stone.

By the mid-15th century, Agostino had begun carving his own niche, quite literally, into the canon of Renaissance sculpture. He diverged from the austere realism of his contemporaries and instead infused his figures with lyrical elegance, decorative flourishes, and an almost ethereal lightness. His reliefs did not merely depict stories, they danced and flowed across the marble like whispered verses of poetry.

Agostino di Duccio is best known for his delicately modeled relief sculptures, often imbued with a unique linear rhythm and almost weightless grace. Unlike the grounded, muscular humanism seen in the works of Michelangelo or Verrocchio, Agostino’s figures are elongated, dreamy, and full of stylized motion, less flesh and more spirit.

His signature works often feature religious and mythological themes, captured in marble with an ornamental touch that reflects the Gothic tradition merging with Renaissance ideals. He preferred shallow reliefs, using incised lines, subtle variations in depth, and fluid drapery to evoke form rather than relying solely on deep carving. His ability to suggest movement and emotion through such minimal intervention with the marble set him apart.

The Making of a Marble Masterpiece

Agostino di Duccio’s approach to sculpture was methodical and expressive. Working primarily in marble, he began each project with preparatory drawings and clay models. These allowed him to study composition and the interplay of light and shadow, elements that would become crucial in his reliefs.

He used a variety of tools, chisels, rasps, drills, to achieve a range of textures. But it was his precision and restraint that impressed patrons. Agostino had a knack for crafting figures that seemed to hover above the stone, dancing delicately across the surface. His style often involved incised lines, creating a sort of pictorial depth that made his sculptures appear like frescoes in stone.

It is also worth noting that Agostino often collaborated with architects and other artists. His ability to adapt his sculptures to architectural settings, like façades, doorways, and altars, was another strength that made him a sought-after artist in both civic and religious projects.

The Dream of Florence: The Unfinished David

Among the most intriguing episodes in Agostino di Duccio’s career is his involvement with a colossal block of Carrara marble that would one day become the David, not by him, but by Michelangelo.

In 1464, the Opera del Duomo of Florence commissioned Agostino to create a giant statue of David for the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore. He began roughing out the figure and carving basic outlines. But by 1466, the project was abandoned, whether due to technical difficulties, disagreements, or political factors remains unclear. The marble remained untouched for decades until, in 1501, a young Michelangelo took over and sculpted his iconic David from the same block. Today, art historians regard Agostino’s initial work on the David as a fascinating “ghost” beneath Michelangelo’s masterpiece, a symbol of ambition and unrealized vision.

Agostino’s Masterwork: The Tempio Malatestiano

Though he left the David incomplete, Agostino di Duccio found enduring glory in another monumental project: the Tempio Malatestiano in Rimini, commissioned by the powerful and controversial Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta, lord of Rimini.

Originally a modest Franciscan church, the Tempio was transformed into a lavish personal mausoleum and statement of power. Between 1449 and 1457, Agostino undertook the creation of a series of stucco and marble reliefs to adorn the chapels inside the temple. These include allegorical figures, angels, musical putti, and scenes celebrating both Christian and classical virtues.

His work in the Chapel of the Planets and the Liberal Arts is especially breathtaking: carved panels filled with elegant female figures personifying celestial bodies and human knowledge. Here, Agostino’s figures take on a dreamlike quality, limbs swaying, drapery billowing, eyes gazing heavenward. The lines are so subtle and the carving so fine that it appears more like drawing in stone than conventional sculpture.

The Tempio Malatestiano remains Agostino di Duccio’s most famous and celebrated work, a unique fusion of Renaissance idealism, Gothic elegance, and humanist symbolism.

Where Are Agostino di Duccio’s Sculptures Today?

Agostino’s works are dispersed across several Italian cities, with key pieces found in:

Rimini: His most iconic and extensive work is housed in the Tempio Malatestiano, including the reliefs of the Liberal Arts, Virtues, and celestial allegories.

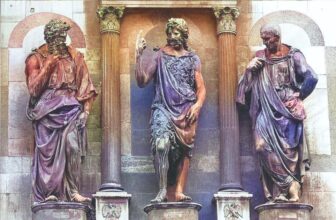

Perugia: In the Oratorio di San Bernardino, Agostino executed a splendid façade featuring saints, angels, and decorative floral motifs. It is a masterpiece of late Gothic-Renaissance synthesis, completed between 1457 and 1461.

Florence: Though he spent much of his early career here and started the David project, few finished works remain in Florence. However, documents and unfinished pieces in Florence’s Opera del Duomo archives confirm his role in the aborted David sculpture.

Modena and Lucca: Lesser-known fragments and minor works attributed to his studio or influence can be found in regional churches and museums.

How Much Are Agostino di Duccio’s Art Sculptures Worth?

Putting a price on a Renaissance masterpiece is no simple matter. Most of Agostino di Duccio’s major sculptures are immovable, embedded in architecture or owned by religious institutions and state museums, and therefore not for sale. However, if a work definitively attributed to him were to come to auction, say, a freestanding marble relief or fragment, it could easily command millions of dollars in today’s art market.

While there have been few, if any, public auction sales of major works by Agostino, comparable pieces by lesser-known Renaissance artists have sold in the range of $500,000 to $5 million, depending on provenance, condition, and subject matter. Agostino’s unique blend of early Renaissance style and decorative linearity would make any verified work a prized acquisition for collectors, institutions, or museums specializing in Quattrocento art.

That said, scholars and curators value Agostino di Duccio’s contributions more for their art historical importance than commercial potential. His influence on relief sculpture, his integration of Gothic and Renaissance idioms, and his role in significant architectural programs make him a cornerstone of 15th-century art.

The Enduring Mystery of Agostino’s Legacy

Agostino di Duccio’s life is shrouded in partial mystery. After his work in Perugia around 1470, little is known of his later years. Some believe he continued producing minor works for churches; others suggest he may have died in relative obscurity.

And yet, his name endures, carved into friezes, chapels, and scholarly treatises. Modern art historians have rediscovered his importance, reevaluating his work as a critical link between the graceful spiritualism of the Gothic era and the human-centered naturalism of the Renaissance.

In many ways, Agostino di Duccio was a sculptor caught between two worlds: not quite medieval, not quite modern. His art occupies a liminal space, where figures float rather than stand, where form suggests rather than declares. He was a poet in marble, a dreamer who sculpted with elegance rather than force.

Agostino di Duccio may never have achieved the monumental fame of his Florentine peers, but his artistry left a permanent impression on the tapestry of Renaissance art. He dared to see sculpture not just as form, but as rhythm, emotion, and grace, a medium for poetry rather than monumentality.

Whether in the hushed chapels of Rimini or the stone-carved portals of Perugia, his works continue to whisper across centuries. They invite us to step closer, to trace the delicate lines of a drapery fold or the curve of a saint’s gaze. In that silent dialogue between stone and soul, the legacy of Agostino di Duccio lives on.