Why Michelangelo’s Last Judgment Was Almost Destroyed

Few works of Renaissance art have stirred as much admiration, awe, and heated debate as Michelangelo Buonarroti’s The Last Judgment. Painted between 1536 and 1541 on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City, this monumental fresco has loomed over visitors for nearly five centuries, commanding their attention with its epic scale, muscular figures, and striking vision of divine judgment. Yet from the moment it was unveiled, The Last Judgment sparked intense controversy. Admirers praised Michelangelo’s genius, but critics accused him of sacrilege, indecency, and arrogance.

Why did this painting cause such uproar? The controversy surrounding The Last Judgment stems from a combination of religious, artistic, and political factors. Michelangelo’s daring artistic choices challenged tradition, clashed with theological expectations, and provoked censors in an era when the Catholic Church was under immense pressure from the Protestant Reformation. To understand the firestorm around this masterpiece, we need to look at its historical context, the painting itself, and the ways it upset both its contemporaries and later generations.

A Church Under Siege

When Michelangelo was commissioned to paint The Last Judgment, the Catholic Church was at a crossroads. The Sistine Chapel had already been decorated by him earlier (the famous ceiling fresco completed in 1512), but by the late 1530s, Europe had changed dramatically.

The Protestant Reformation: Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses (1517) had unleashed a movement that challenged the authority of the papacy, condemned indulgences, and criticized the Church’s excesses. By the 1530s, Protestantism had spread widely, creating deep divisions in Christendom.

The Sack of Rome (1527): The Eternal City had been brutally sacked by imperial troops under Charles V, traumatizing the Church and its citizens. Rome’s grandeur was humbled, and the Church’s spiritual and political power was shaken.

The Council of Trent (1545–1563): Although it began after Michelangelo finished The Last Judgment, this council reflected the Church’s desire to regulate religious art. Art was to be didactic, uplifting, and in line with scripture, not shocking, confusing, or sensually distracting.

Michelangelo’s fresco, created in the tense period between the Reformation’s rise and the Counter-Reformation’s codification, therefore emerged in a world where every image, every artistic choice, could be scrutinized for orthodoxy.

The Painting Itself: A Radical Vision of Judgment Day

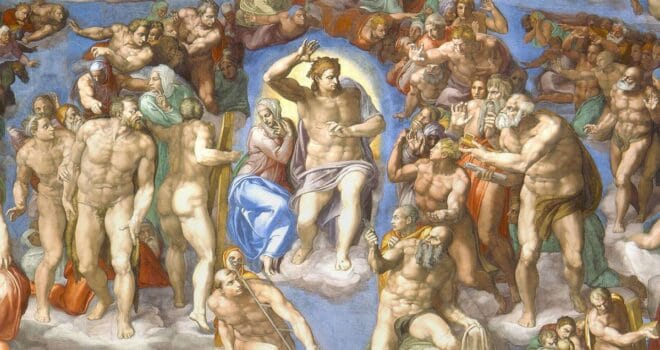

Covering the entire altar wall of the Sistine Chapel, The Last Judgment measures roughly 44 feet high by 40 feet wide. It depicts the Second Coming of Christ and the final judgment of souls, a theme traditionally represented with clear order: Christ enthroned, angels with trumpets, the saved rising to heaven, the damned cast into hell.

Michelangelo kept the broad theme but radically reinterpreted its presentation:

The Central Christ: Instead of the serene, enthroned Christ of medieval tradition, Michelangelo painted a muscular, commanding Christ, raising his arm in a gesture of both condemnation and salvation. His figure recalls classical gods like Apollo or Hercules, blurring the line between Christian iconography and pagan antiquity.

Dynamic Movement: The fresco is filled with swirling, turbulent figures, angels, saints, and resurrected souls. Rather than neat rows or hierarchies, chaos reigns. Bodies twist, strain, and spiral, suggesting an almost apocalyptic energy.

Nudity Everywhere: Most figures are nude or nearly nude, their bodies painted with Michelangelo’s signature sculptural precision. For Michelangelo, the human body was a divine creation worthy of celebration. But for many clergy, the abundance of flesh was scandalous and inappropriate for a sacred space.

Saints with Instruments of Martyrdom: Surrounding Christ are saints holding symbols of their suffering, St. Bartholomew with his flayed skin, St. Catherine with her broken wheel, St. Sebastian with arrows. The realism of these tools added a grotesque quality that unsettled some viewers.

Inclusion of Hell: At the bottom right, the damned are dragged into hell by demons, ferried by Charon (a figure borrowed from Greek mythology), and judged by Minos, another pagan reference. This blending of Christian and classical imagery fueled accusations of blasphemy.

The Immediate Backlash: Nudity, Paganism, and Power

When unveiled in 1541, the fresco provoked immediate debate. While many admired Michelangelo’s virtuosity, others were outraged. Several specific criticisms stand out:

1. Indecency of Nudity

The most famous objection was to the widespread nudity of the figures. Critics argued that such displays were unbecoming of a papal chapel, a place of worship. They worried that worshippers would be distracted by sensuality instead of spiritual reflection.

The charge of obscenity grew so intense that one critic, Biagio da Cesena (the Pope’s Master of Ceremonies), denounced the fresco as more suitable for a public bathhouse than a chapel. In retaliation, Michelangelo painted Cesena’s portrait as Minos, judge of the underworld, with donkey ears and a snake biting his genitals, a humiliating caricature that immortalized their feud.

2. Pagan Influences

Michelangelo’s inclusion of mythological figures like Charon and Minos scandalized theologians. Why, they asked, should a Christian depiction of Judgment Day borrow imagery from ancient pagan mythology? To them, this diluted the sacred message and polluted Christian doctrine with “heathen” elements.

3. Christ as Judge

Instead of a majestic, distant ruler, Michelangelo’s Christ was muscular, almost aggressive, more reminiscent of a classical hero than the traditional compassionate Savior. This departure from iconography was seen by some as heretical, undermining Christ’s spiritual authority.

4. Power and Politics

Because Michelangelo was given enormous freedom by Pope Paul III, some saw the fresco as a symbol of papal overreach, an extravagant, self-indulgent project at a time when the Church was under attack for its excesses. Others accused Michelangelo of arrogance, claiming he had imposed his own vision of judgment rather than adhering to theological guidance.

The Counter-Reformation and Censorship

The controversy did not end in Michelangelo’s lifetime. In 1563, during the Council of Trent, the Catholic Church decreed that religious art must avoid “lasciviousness” and indecency. This directive was widely interpreted as a direct response to The Last Judgment.

In 1565, under Pope Pius IV, artist Daniele da Volterra was commissioned to cover the most explicit nudes with painted draperies and cloths. These alterations earned him the mocking nickname “Il Braghettone” (“the breeches-maker”). Though some of Michelangelo’s original figures remained uncovered, the overall impact was blunted.

Later popes considered removing or destroying the fresco altogether, but its fame as a masterpiece preserved it. Restoration in the 20th century removed some later additions, though the “breeches” remain in certain areas, reminding viewers of the painting’s fraught history.

The Artistic Legacy of the Controversy

Ironically, the very elements that scandalized critics, nudity, dynamism, pagan references, also made The Last Judgment one of the most influential works of Renaissance art. Artists across Europe studied its composition, anatomy, and energy. The fresco became a symbol of artistic freedom, even defiance, against rigid religious norms.

Yet the controversy also reshaped the role of art in the Church. After The Last Judgment, religious authorities exercised stricter control over artistic commissions. The baroque art of the Counter-Reformation, exemplified by artists like Caravaggio, still embraced drama and realism but avoided overt nudity or ambiguity.

Broader Themes Behind the Controversy

Looking deeper, the controversy around Michelangelo’s Last Judgment reveals broader tensions between art, religion, and power:

Body vs. Spirit: For Michelangelo, the human body was divine beauty made visible. For critics, it was a source of temptation that distracted from spiritual truths. This tension still resonates today in debates about censorship and representation.

Tradition vs. Innovation: Michelangelo broke from medieval iconography to create a bold new vision. His critics wanted adherence to tradition and clarity in religious teaching. The clash reflected larger struggles between Renaissance humanism and conservative theology.

Individual Genius vs. Institutional Authority: Michelangelo asserted his personal vision, while the Church insisted on art serving doctrine. The conflict highlighted the uneasy relationship between individual creativity and institutional control.

Modern Reception: From Scandal to Masterpiece

Today, most visitors to the Sistine Chapel marvel at The Last Judgment without feeling scandalized. What once seemed indecent now appears as high art. Scholars interpret the nudity as symbolic of the soul stripped bare before divine judgment, and the pagan elements as evidence of Renaissance humanism’s blending of classical and Christian traditions.

Restoration projects in the 1980s and 1990s cleaned centuries of grime from the fresco, revealing its original vibrancy. While some debate continues over whether the restoration went too far, the work’s brilliance is undeniable.

Yet the historical controversies remain part of the fresco’s identity. They remind us that art does not exist in a vacuum; it provokes, challenges, and reflects the anxieties of its time.

Why the Last Judgment Was, and Still Is, Controversial

Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment was controversial because it shattered expectations. It filled a sacred space with turbulent bodies, borrowed from pagan myth, depicted Christ as a muscular avenger, and exposed humanity’s nakedness before divine power. At a moment when the Catholic Church was under siege, such boldness was both admired and condemned.

The controversy reveals the power of art to unsettle as much as inspire. It shows how questions of decency, doctrine, and artistic freedom have long been contested. And it proves that Michelangelo’s genius lay not only in his technical mastery but in his willingness to push boundaries, even in the holiest chapel of Christendom.

Nearly 500 years later, the fresco continues to awe, provoke, and spark debate. That enduring capacity for controversy may, in the end, be Michelangelo’s greatest triumph.