The Last Supper and the Number Thirteen: Secrets and Mysteries

Shopping Ads: Antique Oil Paintings On Canvas For Sale. Limited Originals Available 💰😊

Authentic hidden masterpieces, Explore old master antique oil paintings from the Renaissance and Baroque eras. From 15th-century to 18th-century Antique Paintings. Bring the Renaissance and Baroque in your home. Shop Now!

🎨 Antique Oil Paintings On Canvas Renaissance, Baroque Art Antique Oil Paintings, Make Offer 16th to 18th Century Portrait Paintings

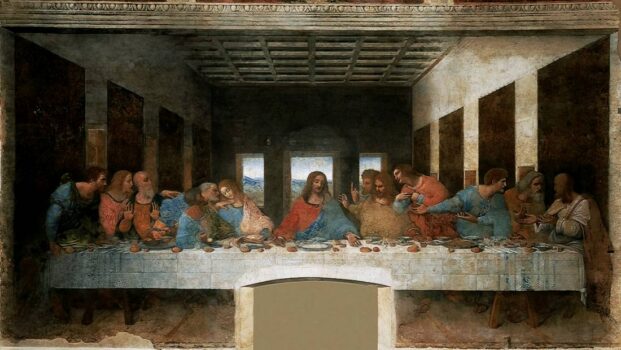

Few paintings in history have attracted as much speculation, reverence, and controversy as The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci. More than five centuries after it was painted on the walls of the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, it continues to inspire questions about hidden meanings, secret codes, and spiritual mysteries. At the center of this fascination lies a curious superstition: the number thirteen. The idea that thirteen people sitting at a table spells doom has become one of the most enduring superstitions of the Western world, and it is rooted deeply in the story of Christ’s last meal with his apostles. But how much of this fear comes from biblical history, and how much has been fueled by Da Vinci’s daring artistic choices?

This is not just a story about art, it is a story about religion, myth, psychology, and society. To understand the secrets of The Last Supper, one must peel back layers of symbolism, historical context, and human imagination.

The Superstition of Thirteen at a Table

The belief that it is unlucky for thirteen people to sit down together at a table is so widespread that even today many avoid it. Some hotels do not have a “thirteenth floor,” and some families refuse to set thirteen places for a meal. This superstition has roots in several traditions, but its most famous origin story is the Last Supper of Jesus Christ.

According to the New Testament, Christ gathered his twelve apostles on the night before his crucifixion to share bread and wine. It was here that he announced that one of them would betray him. Judas Iscariot, seated among the group, was the thirteenth person at the table. By the end of that night, Jesus would be arrested, and the events of his passion would begin.

This connection of betrayal and tragedy with the number thirteen burned into Christian culture. The Norse myths add another eerie parallel: in one story, twelve gods were feasting in Valhalla when Loki, the trickster, arrived as the thirteenth guest and chaos followed. Across cultures, then, thirteen became a symbol of disruption and danger, especially when tied to communal meals.

When Leonardo da Vinci chose to immortalize this fateful supper, he wasn’t simply painting a religious scene, he was capturing the very moment when this superstition was born.

Leonardo’s Bold Experiment

Leonardo da Vinci painted The Last Supper between 1495 and 1498 under commission from Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan. Rather than use traditional fresco techniques, Leonardo experimented with tempera and oil on dry plaster, hoping for greater detail and luminosity. This choice, unfortunately, led to early deterioration, but it also allowed him to imbue the work with unmatched psychological intensity.

Unlike earlier depictions, Leonardo did not portray the apostles in stiff, saintly stillness. Instead, he froze them in the exact moment after Christ’s shocking revelation: “One of you will betray me.” The table explodes with emotion, shock, anger, denial, whispers, and gestures ripple through the group. Each apostle reacts differently, as if Leonardo wanted to reveal not only the drama of the moment but also the inner personalities of the men themselves.

And there, at the center, sits Jesus. Calm, resigned, yet majestic, his hands stretch outward, symbolically toward the bread and wine that will become the Eucharist.

But hidden within this famous composition are details that have sparked centuries of debate.

The Secrets Hidden in The Last Supper

1. The Mystery of Judas

In earlier medieval art, Judas was often isolated, sometimes placed on the opposite side of the table, visually separated from the apostles. Leonardo broke this tradition. He seats Judas with the others, but subtly marks him out: he is shadowed, clutching a small bag (perhaps the silver he was paid for betrayal), and he knocks over a salt cellar with his elbow, a gesture long associated with bad luck.

To Renaissance viewers, the spilled salt would have been a clear symbol of corruption and treachery. Was Leonardo trying to say that Judas was not entirely alien, but human like the others, capable of weakness, greed, and poor choices?

2. The Sacred Geometry

Many have argued that Leonardo embedded mathematical harmony within the composition. The apostles are arranged in four groups of three, reinforcing the number three, symbolic of the Trinity. Christ forms a perfect triangular shape, the most stable of geometric forms, at the center of the painting.

Some researchers suggest that Leonardo, obsessed with mathematics and sacred proportion, built the painting on the principles of the “golden ratio.” Whether intentional or not, the painting’s geometry conveys balance even amid emotional chaos.

3. The Figure Beside Christ

Perhaps the most controversial debate of all: who sits immediately to Christ’s right (the viewer’s left)? Traditionally identified as the apostle John, this figure appears strikingly feminine, flowing hair, delicate features, and a youthful softness that has led some to speculate it is not John at all, but Mary Magdalene.

This theory gained worldwide fame after Dan Brown’s novel The Da Vinci Code, which suggested that Leonardo deliberately placed Magdalene beside Christ to hint at a secret relationship between them. While most art historians insist it is John, known in medieval tradition as “the beloved disciple” often depicted as youthful and gentle, the ambiguity continues to fuel popular imagination.

4. The Missing Cup

Curiously, there is no chalice, no grand cup of the Holy Grail, in Leonardo’s depiction. Earlier paintings often highlighted the Grail, central to medieval legends. Leonardo leaves only simple glasses of wine on the table, as though stripping away myth to emphasize the humanity of the moment. Some theorists argue that Leonardo was deliberately rejecting the Grail legend, while others claim he hid it in plain sight, in the very body and presence of Christ himself.

5. The Music Hidden in the Painting

In 2007, a researcher suggested that the positions of hands and loaves of bread across the painting resemble musical notes. When transcribed onto a staff, they form a short melody that some interpret as sacred music. Whether coincidence or intention, the idea that Leonardo embedded a secret song into The Last Supper only adds to its aura of mystery.

The Controversies Surrounding Da Vinci’s Masterpiece

The Decay and Restoration

Almost immediately after its completion, The Last Supper began to deteriorate due to Leonardo’s experimental technique. By the 16th century, viewers reported large areas were already flaking away. Over the centuries, misguided restorations further damaged it. By the 20th century, it was barely recognizable.

A major restoration from 1978 to 1999 attempted to recover Leonardo’s original vision, using microscopes and careful cleaning to strip away centuries of repainting. The result remains controversial: some praise its delicacy, others claim too little of Leonardo’s true brushwork survives.

The “Heretical” Interpretations

From the suggestion that Mary Magdalene is present to claims of secret codes hidden in geometry, Da Vinci’s painting has often been accused of heresy or esoteric symbolism. Did Leonardo intend to challenge the Church’s narrative, or was he simply a master of psychological realism misunderstood by later generations?

The Catholic Church, though wary of wild theories, has never officially condemned the work. Still, the tension between sacred orthodoxy and speculative interpretation continues to swirl around the mural.

The Cultural Storm of The Da Vinci Code

The release of Dan Brown’s 2003 novel catapulted The Last Supper into pop culture in unprecedented ways. Millions of readers came to believe that Leonardo had encoded a suppressed history, that Jesus married Mary Magdalene, that the Church covered up their descendants, and that The Last Supper was the visual proof.

Historians widely dismiss these claims as fiction, but the controversy sparked global debates about the role of women in Christianity, the history of the Church, and the ways art can be reinterpreted in different eras.

The Deeper Meaning of the Thirteenth Seat

At its heart, the superstition of thirteen at the table is not just about numbers. It is about fear of betrayal, mortality, and the fragile bonds of human community. Da Vinci’s painting immortalizes this very fear: the anxiety that among friends and family, there may lurk disloyalty, weakness, or tragedy.

Yet Leonardo also offers balance. The composition radiates harmony, and Christ at the center embodies serenity amid turmoil. The thirteenth guest may be unlucky, but the thirteenth presence also fulfills destiny, leading to sacrifice, redemption, and renewal.

Perhaps this is the ultimate secret of The Last Supper: that within betrayal lies the seed of salvation, and within superstition lies the human need to find meaning in chaos.

Why The Last Supper Still Captivates

Five hundred years later, millions still travel to Milan to gaze upon the fragile remnants of The Last Supper. They come not only to admire Leonardo’s genius but also to touch a mystery that continues to evade final explanation.

Is the figure beside Jesus John or Mary Magdalene?

Did Leonardo embed codes, songs, or symbols meant only for the initiated?

Was he challenging the Church, or simply elevating art to a new psychological realism?

The answers may never be certain. But perhaps that is precisely why the painting endures. Each generation finds new secrets in its shadows, new meanings in its silence.

Between Faith and Imagination

The superstition of thirteen at the table, the secrets hidden in Leonardo’s masterpiece, and the controversies it has inspired all point to the same truth: The Last Supper is more than a painting. It is a mirror of humanity’s deepest fears and hopes.

Leonardo da Vinci transformed a familiar biblical story into a timeless meditation on loyalty, betrayal, fate, and the search for hidden truth. He left us not with answers, but with questions, questions that keep the painting alive in the collective imagination.

So when we sit at a table of thirteen and feel a shiver, or when we stand before Leonardo’s fading mural in Milan, we are touching the same mystery: that art, superstition, and faith are woven together in ways that defy time.

And perhaps that is Leonardo’s greatest secret, not a code hidden in paint, but the reminder that the deepest mysteries are those that cannot be solved, only contemplated.