Aurora of Guido Reni: Story, Symbolism and Meaning

Few works of Baroque art capture the poetic spirit of mythology, beauty, and celestial radiance quite like Guido Reni’s Aurora. Painted in 1614, this masterpiece has long been admired not only for its technical perfection but also for the mythological narrative it conveys. Even centuries later, Aurora continues to inspire fascination, scholarly analysis, and debate. To truly understand the painting, one must look beyond its immediate beauty and explore the story it tells, the circumstances of its creation, the symbolism embedded within, and the way it has been received through time.

The Story Behind Aurora

The painting was commissioned in 1614 by Cardinal Scipione Borghese, the powerful nephew of Pope Paul V and one of the greatest art patrons of his age. At the time, Rome was the epicenter of the Catholic Counter-Reformation, and wealthy church officials often sought to express their prestige and sophistication through art. Borghese wanted a fresco that would decorate the ceiling of the Casino dell’Aurora, a small garden pavilion adjacent to the Palazzo Pallavicini-Rospigliosi in Rome.

Guido Reni, already celebrated for his refinement and grace, was chosen for this important commission. Unlike Caravaggio, who painted with dramatic shadows and gritty realism, Reni’s style was more ethereal, harmonious, and influenced by classical ideals. The Aurora fresco would become one of his most celebrated achievements and a testament to his ability to combine mythological storytelling with technical brilliance.

The Aurora Mythological Subject

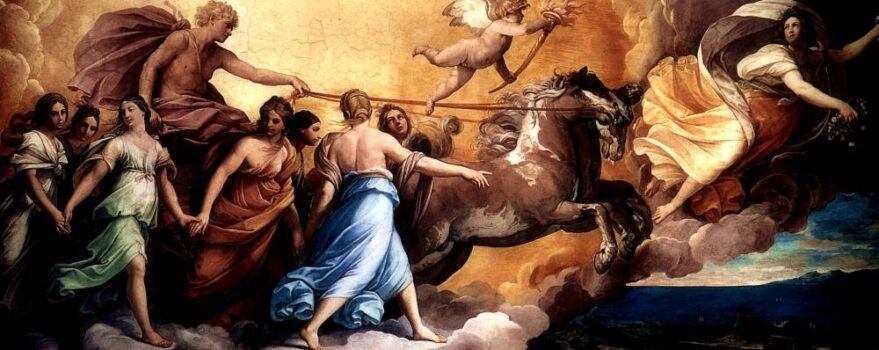

The painting illustrates the daily journey of Apollo, the sun god, across the heavens. According to Greco-Roman mythology, Apollo drove a radiant chariot pulled by fiery horses to bring daylight to the world. Preceding him is Aurora, the goddess of dawn, who heralds his arrival. Aurora is often associated with freshness, renewal, and the promise of a new beginning.

The fresco captures this eternal cycle: Aurora spreads flowers to announce the morning, Apollo rides in his golden chariot, and a group of maidens, known as the Hours (Horae), dance gracefully around him, symbolizing the passage of time. Above, a winged cherub personifies the Morning Star, guiding Apollo’s path.

The narrative is not just about myth; it is about the cosmic order, the triumph of light over darkness, and the cyclical renewal of life itself.

How Aurora Was Painted

Unlike oil paintings on canvas, Aurora is a fresco, painted directly onto the ceiling plaster while it was still wet. This method required meticulous planning, as the artist had to apply pigments quickly before the plaster dried. Fresco painting was considered one of the most demanding forms of art, leaving little room for error.

Reni used luminous colors, refined contours, and an almost sculptural clarity to give the figures a sense of weightlessness. His composition is framed within a painted architectural border, giving the illusion of a framed canvas hanging above the viewer rather than a ceiling fresco. This innovative choice distinguished Reni’s work from other grand ceiling frescoes of the Baroque period, such as those by Pietro da Cortona or Andrea Pozzo, which sought to dissolve boundaries and create overwhelming illusionistic spaces.

Instead, Reni offered restraint, harmony, and a sense of classical balance, qualities that made Aurora unique in its time.

At the time of Aurora’s creation, artistic taste was divided between the dramatic naturalism of Caravaggio and the idealized classicism of the Carracci school, from which Reni emerged. Aurora reflects Reni’s allegiance to the latter: an art rooted in clarity, balance, and beauty rather than violence and shadow.

This stylistic choice was not accidental. For Borghese and his circle, the painting’s serenity and elegance reflected the sophistication of their intellectual and cultural ideals. It projected order, refinement, and a connection to classical antiquity, values that matched the grandeur of their social standing.

What Aurora Represents

Symbolism of the Figures

Aurora (Dawn): Aurora leads the procession, scattering flowers in her wake. She symbolizes renewal, freshness, and the promise of a new day. Her role as a bringer of light reflects spiritual awakening and the hope of enlightenment.

Apollo (the Sun God): Riding in a golden chariot, Apollo represents light, truth, and divine order. His radiant halo and commanding presence make him the central figure of the scene, embodying the unstoppable force of time and cosmic balance.

The Hours (Horae): These graceful maidens dance around Apollo’s chariot. They symbolize the cyclical nature of time, spring, summer, autumn, winter, and the eternal passage of day into night, night into day.

The Cherub (Morning Star): The winged figure flying above is the Morning Star, also called Phosphorus or Lucifer in classical mythology. This star heralds Apollo’s coming, marking the transition from darkness to light.

Aurora Philosophical and Religious Meaning

Though mythological on the surface, Aurora can be read as an allegory for spiritual illumination. In the Counter-Reformation context, the triumph of light over darkness symbolized the victory of divine truth over sin. Apollo, the bringer of light, could also be interpreted as a Christ-like figure, with Aurora symbolizing the Church that prepares the way.

At the same time, the painting celebrated the patron’s power and refinement. By decorating his villa with an image of divine order and celestial beauty, Cardinal Borghese aligned himself with both the grandeur of antiquity and the eternal harmony of the cosmos.

What Is Happening in the Aurora Painting

At first glance, the viewer sees a radiant procession across the sky. Aurora, dressed in flowing robes, moves ahead of Apollo, casting flowers into the air. Apollo follows in his gilded chariot, drawn by spirited horses that gallop forward energetically. Surrounding him are the dancing Horae, holding hands in a circular rhythm. Above, the cherub of the Morning Star hovers, illuminating the path.

The entire composition seems to glide horizontally across the canvas-like frame, suggesting motion and continuity. Unlike chaotic Baroque frescoes that tumble with dramatic foreshortening, Reni’s Aurora is measured, controlled, and balanced. It is not a violent burst of energy but a harmonious dance of cosmic order.

The Type of Art Aurora Represents

Aurora is a quintessential example of Baroque classicism. While it belongs to the Baroque period, it avoids theatrical excess and instead emphasizes clarity, elegance, and classical restraint. Its influences trace back to Raphael, whom Reni deeply admired, particularly in the fresco’s graceful lines and harmonious proportions.

It is also a mythological fresco, a genre that allowed artists to explore allegory, beauty, and universal themes through ancient stories. Unlike religious frescoes meant to inspire devotion, mythological works like Aurora were intended to impress, delight, and provoke intellectual reflection.

Where is the Location of Aurora Today

The fresco remains in situ, meaning it is still in its original location: the Casino dell’Aurora Pallavicini in Rome, near the Quirinal Hill. The villa is privately owned by the Pallavicini family, descendants of the Borghese patrons.

Because of its private ownership, Aurora is not as easily accessible as works in public museums. However, the villa occasionally opens for guided visits, making it a rare treasure for art lovers who wish to experience it in person. This exclusivity has only added to the painting’s mystique.

Mysterious Aspects of Aurora

Though not associated with curses or supernatural legends, Aurora carries its own mysteries.

The Morning Star’s Ambiguity: The winged cherub above Apollo is sometimes identified as Lucifer, the light-bringer. This duality, Lucifer as both the herald of light and the fallen angel, adds a layer of ambiguity to the painting. Some scholars wonder whether Reni intentionally played on this double meaning.

The “Framed Canvas Illusion”: Unlike typical ceiling frescoes that dissolve architectural space, Reni chose to frame Aurora within a painted border. This unusual choice has puzzled historians. Was it a nod to Raphael’s classical balance? Or a subtle critique of Baroque illusionism? The answer remains debated.

Reni’s Character: Reni himself was known to be a deeply superstitious man, often consulting astrologers and horoscopes. Some suggest that his personal beliefs may have influenced the celestial subject matter of Aurora.

These small mysteries add intrigue, inviting endless reinterpretation.

Reception

Since its unveiling in the early 17th century, Aurora has been admired as one of Reni’s greatest masterpieces.

Praise

Artistic Harmony: Visitors and critics have long praised the fresco for its elegance, balance, and clarity. Johann Joachim Winckelmann, the great art historian, admired Reni for reviving the classical spirit of antiquity.

Technical Perfection: The fresco’s smooth contours and radiant palette were often seen as evidence of Reni’s mastery, contrasting with the raw intensity of Caravaggio.

Symbolic Richness: Scholars and viewers appreciate its allegorical depth, which resonates on mythological, philosophical, and religious levels.

Criticism

Not all have been equally impressed.

Some critics argue that Reni’s style, while beautiful, can appear too cold or idealized compared to the emotional power of Caravaggio or Rubens.

In later centuries, Romantic-era viewers found Reni’s restraint lacking in passion, dismissing him as overly academic.

Today, most art historians view Aurora as a pivotal work of Baroque classicism. Tourists who manage to see the fresco in Rome often describe the experience as breathtaking, praising its vibrant colors and serene grace. Some, however, find it less dramatic compared to the overwhelming illusionism of later Baroque ceilings.

In short, Aurora continues to spark admiration and debate, embodying the enduring complexity of Reni’s art.

Guido Reni’s Aurora is far more than a mythological ceiling decoration, it is a meditation on time, renewal, and the triumph of light. Painted in 1614 for Cardinal Scipione Borghese, it represents the height of Baroque classicism, balancing mythological narrative with philosophical symbolism. Aurora heralds Apollo, the Horae dance, and the Morning Star guides, a cosmic procession that reflects both the harmony of the universe and the sophistication of its patron.

Its mysteries, from the identity of the Morning Star to the unusual framed composition, invite endless interpretation. Its reception, ranging from enthusiastic praise to critiques of coldness, shows the painting’s enduring power to provoke thought. And its continued presence in the Casino dell’Aurora makes it not only a masterpiece of art but also a rare treasure of cultural heritage.

Ultimately, Aurora is a work about renewal: the eternal cycle of dawn, the rebirth of light, and the promise of a new day. Over four centuries later, it still awakens in viewers the same sense of awe it was meant to inspire, an immortal dawn painted upon a ceiling.