Nastagio degli Onesti, Part One by Sandro Botticelli

Summary:

The Story of Nastagio degli Onesti, Part One is a narrative panel painting executed by the Italian Renaissance master Sandro Botticelli around 1483. It forms the first scene in a four-panel cycle illustrating an episode from Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron (Day Five, Novel Eight). Commissioned by the Florentine merchant Antonio Pucci, likely as a wedding gift for his son Giannozzo Pucci, the series reflects both moral instruction and social aspiration. Botticelli’s painting combines literary storytelling, courtly culture, and innovative Renaissance pictorial techniques to convey a dramatic tale of love, cruelty, and supernatural justice.

The story centers on Nastagio degli Onesti, a young nobleman from Ravenna who is deeply in love with a woman of higher social standing. Despite his wealth and devotion, his love is unreciprocated; the woman treats him with disdain and cruelty. In despair, Nastagio retreats into a pine forest near the sea, contemplating suicide and the futility of love. It is within this liminal, natural space that the supernatural elements of the story unfold. Botticelli’s first panel captures this pivotal moment, introducing the psychological state of the protagonist and the violent apparition that will alter the narrative’s course.

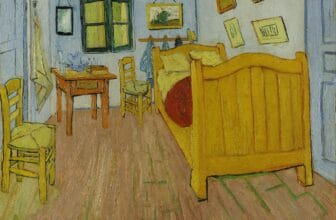

Visually, the composition is structured as a continuous narrative, a common Renaissance device in which multiple moments of a story are depicted within a single unified space. Botticelli situates the scene in a stylized coastal pine forest, inspired by the landscape near Ravenna. The forest is orderly and rhythmic, with evenly spaced trees that create depth and guide the viewer’s eye across the panel. This controlled natural environment reflects Renaissance ideals of harmony and proportion, even as it becomes the setting for a disturbing and violent event.

On the left side of the painting, Nastagio is shown walking alone, dressed in fashionable contemporary Florentine attire. His posture and gesture convey agitation and emotional distress; he appears caught mid-step, turning toward the terrifying vision unfolding before him. Botticelli deliberately dresses Nastagio in 15th-century clothing rather than medieval costume, collapsing historical distance and allowing contemporary viewers to identify more closely with the protagonist. This anachronism underscores the moral relevance of the story for Botticelli’s audience.

The central and right portions of the painting depict the supernatural punishment that Nastagio witnesses. A naked young woman runs desperately through the forest, pursued by a knight on horseback and a pack of fierce dogs. The knight, identified in the story as Guido degli Anastagi, is a nobleman who committed suicide after being rejected by the same cruel woman he loved in life. As punishment for their sins, his suicide and her merciless rejection, the two are condemned to reenact this violent chase every Friday. The dogs repeatedly tear the woman’s flesh, and the knight kills her, only for her body to be restored so the punishment can begin again.

Botticelli renders this gruesome subject with striking clarity but controlled restraint. Blood is visible, and the violence is unmistakable, yet the figures maintain an elegant linearity characteristic of Botticelli’s style. The woman’s body, though subjected to brutality, is idealized according to Renaissance standards of beauty. This aesthetic tension between beauty and cruelty heightens the emotional impact of the scene and reflects the moral ambiguity of the narrative itself.

The knight’s posture is rigid and authoritative, emphasizing the inevitability of divine justice. His raised sword and commanding presence contrast with the woman’s vulnerability and terror. The dogs, animated and aggressive, serve as instruments of punishment rather than mere animals. Nastagio, as witness, occupies a crucial narrative role: he bridges the human and supernatural realms and becomes the recipient of the moral lesson embedded in the vision.

The painting’s function extends beyond mere illustration. As a wedding commission, the Nastagio panels carried a didactic message aimed at the bride. The story ultimately concludes with Nastagio using this terrifying vision to persuade his beloved to marry him, thereby restoring social and emotional order. In this context, the first panel establishes the consequences of cruelty in love, reinforcing contemporary expectations of female obedience and marital duty. While modern viewers may find the moral troubling, it reflects the gender norms and social structures of Renaissance Florence.

From an artistic standpoint, The Story of Nastagio degli Onesti, Part One demonstrates Botticelli’s mastery of narrative clarity and spatial organization. The landscape is both decorative and functional, guiding the story’s progression across the panel. The figures are defined by clean contours and expressive gestures rather than heavy modeling, consistent with Botticelli’s preference for line over volume. Color is used sparingly but effectively, with earthy tones dominating the landscape and brighter hues highlighting the figures to ensure narrative legibility.

The painting also reveals the influence of humanist culture, which valued classical literature, moral exempla, and the fusion of art and text. By translating Boccaccio’s literary narrative into visual form, Botticelli participates in a broader Renaissance project of elevating vernacular literature and integrating it into elite visual culture.

In summary, The Story of Nastagio degli Onesti, Part One is a richly layered work that combines literary narrative, moral instruction, and aesthetic refinement. Through its depiction of despair, supernatural justice, and the power of witnessed violence, the painting sets the foundation for the unfolding story across the remaining panels. It exemplifies Botticelli’s ability to balance beauty with narrative intensity and offers valuable insight into the social values, artistic practices, and storytelling traditions of the Italian Renaissance.

The Story of Nastagio degli Onesti

Few Renaissance artworks blend romance, cruelty, moral instruction, and political symbolism as vividly as Sandro Botticelli’s The Story of Nastagio degli Onesti. Painted in 1483 as a lavish wedding gift commissioned by the powerful Medici family, this series transforms a tale from Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron into four extraordinary visual narratives, each panel a window into love, vengeance, wealth, and the dark side of social pressure in Renaissance Florence.

Today, the panels survive as some of the most fascinating, and sometimes controversial, examples of Italian Renaissance storytelling. They are prized not only for their beauty but also for what they reveal about gender dynamics, power, and social expectations in 15th-century Florence.

This in-depth article explores every dimension of Botticelli’s series:

What the story is about

Who commissioned it and how Botticelli painted it

Its symbolism and deeper meaning

What is happening in each painting

Its art-historical importance

Controversies and modern criticism

Public opinion then and now

Where the paintings are located today

Let’s journey through this haunting Renaissance narrative.

What Is “The Story of Nastagio degli Onesti” About?

The story originates from Boccaccio’s Decameron, Day V, Novel 8, a medieval masterpiece filled with tales of love, tragedy, and morality. Nastagio’s tale blends horror and romance, a combination that captivated Renaissance patrons.

The Narrative in Brief

Nastagio degli Onesti, a wealthy young nobleman of Ravenna, is hopelessly in love with a woman who rejects him coldly. Consumed by heartbreak and humiliation, he retreats into a forest to consider his fate. There, he witnesses a terrifying supernatural hunt:

A knight, once a lover rejected by a cruel woman, eternally hunts the woman who spurned him.

Each week, he catches her, kills her, and tears out her heart, only for her to be resurrected to repeat the punishment.

Nastagio realizes this hellish scene is a punishment for cruelty, a divine warning to women who mock sincere love. He cleverly uses it to his advantage, arranging for the woman he loves, and the whole town, to witness the gruesome spectacle. Terrified, she agrees to marry him out of fear of sharing the same fate.

Thus, the medieval tale becomes a moral:

Cruelty in love brings divine punishment; compassion is rewarded.

It is a story about:

Unrequited love

Power and persuasion

Fear used as social coercion

Justice vs. brutality

The fragility of love in hierarchical societies

Who Painted The Story of Nastagio degli Onesti, And Why?

Artist: Sandro Botticelli (1445–1510)

One of the great masters of the Early Renaissance, Botticelli produced these panels during a peak moment in his career. Just a few years earlier, he had completed Primavera and The Birth of Venus.

Commissioner: Lorenzo de’ Medici

The works were commissioned as part of a wedding gift for Giannozzo Pucci and Lucrezia Bini, members of influential Florentine families connected to the Medici circle.

Purpose: Marriage Propaganda and Social Messaging

These paintings were not merely decorative. They served a didactic purpose, a visual reminder that:

Harmony in marriage is essential

Women must be obedient

Men’s desires should be honored

Wealth and marital unity strengthen social networks

In Renaissance Florence, art was a political tool. Botticelli’s panels were intended to emphasize the ideals of marriage (from a very male-dominated viewpoint) and to remind the bride of her social and emotional duties.

How Botticelli Painted the Series: Techniques and Style

Botticelli worked in tempera on panel, a medium typical of the time. His process involved:

A detailed underdrawing

Layered pigments with egg tempera

Careful modeling of figures with almost sculptural precision

Key Stylistic Features

Delicate linework typical of Botticelli

Graceful but elongated bodies

Rhythmic, decorative movement in clothing and landscape

Narrative sequencing, with multiple time moments depicted in one scene

Bright, festive colors, because the panels were meant for a nuptial bedroom

Even the violent scenes are painted with Botticelli’s characteristic elegance, creating a powerful contrast between horror and beauty.

What Is Happening in the Paintings? (Panel-by-Panel Breakdown)

The cycle consists of four panels, each depicting a stage of the tale.

Panel I – Nastagio Encounters the Ghostly Hunt

The first scene shows the lovesick Nastagio wandering in the pine forest near Ravenna. Suddenly he witnesses:

A nude young woman, terrified, running through the trees

A violent knight on horseback chasing her

Black hunting dogs tearing at her flesh

This is the moment when the supernatural intersects the earthly world. The knight explains that they are trapped in eternal punishment for the woman’s cruelty.

Symbolism

Forest: chaos, danger, transformation

Nude woman: vulnerability, exposure of guilt

Knight: vengeance and male authority

Hounds: divine justice, relentless fate

The message is clear: cruelty has consequences beyond death.

Panel II – The Killing of the Woman

In the second panel, the dramatic climax unfolds. The knight kills the woman in front of Nastagio, removes her heart, and feeds it to the dogs.

Symbolism

Heart: the seat of emotions, being “torn out” because she withheld love

Dogs: instruments of fate and judgment

Nastagio’s witnessing: he becomes a participant in the moral spectacle

This panel is the most graphically intense, yet painted with remarkable serenity.

Panel III – The Banquet and the Horror as Spectacle

Nastagio uses the event to persuade the woman he loves. He invites guests, including her family, to a grand feast in the forest at the exact time the ghostly hunt reappears.

As the horrified nobility watches the ghost woman’s weekly punishment, Nastagio’s beloved and her relatives receive a chilling message.

Symbolism

Banquet: social life interrupted by divine justice

Audience reaction: fear as a tool of persuasion

Aristocratic clothing: the continuity between myth and real Florence

Panel IV – The Marriage

The final panel is calm and celebratory. Nastagio marries the once-unwilling woman, now convinced that refusing him might doom her to the same fate as the punished ghost.

Symbolism

Wedding procession: social harmony restored

Jewelry and finery: union of wealthy families

Flower garlands: marital fertility

Domestic architecture: stability in married life

The narrative arc ends with triumph for the groom and compliance for the bride.

What Type of Art Is The Story of Nastagio degli Onesti?

This series belongs to three overlapping art categories:

1. Renaissance Narrative Painting

A popular form where artists visualized stories from literature, mythology, or legend.

2. Cassone Painting (Marriage Chest Art)

These panels were likely intended for a bridal bedroom or the decorative cassoni (marriage chests). Such artworks often taught moral lessons.

3. Secular Mythological/Literary Painting

Though rooted in a moral message, the imagery is not religious; instead, it comes from Boccaccio’s secular literature.

This mixture made the panels highly appealing to wealthy Renaissance families who used art to express education, wealth, and cultural sophistication.

What Does The Story of Nastagio degli Onesti Represent?

Botticelli’s panels are packed with symbolic meaning. Their themes resonate with Renaissance society but also provoke modern discussions.

Love and Cruelty

At its core, the story explores:

The pain of unrequited love

The consequences of emotional coldness

How love can transform into punishment or violence

Control and Persuasion

The tale suggests that persuasion through fear, even terror, can lead to desired outcomes. Nastagio’s use of the supernatural spectacle reflects:

The male dominance of Renaissance marriage

The idea that women should be “guided” into obedience

Marriage as a social contract, not a romantic ideal

Social Expectations

Marriage was essential for political alliances. The panels remind viewers, especially brides, of their social duties.

Divine Justice

The supernatural punishment is framed as “fair” justice for unkindness, echoing medieval beliefs.

Spectacle and Morality

Botticelli paints horror with beauty, making the viewer both drawn to and repulsed by the scenes. This duality invites reflection on how society uses fear to enforce norms.

Symbolism and Deeper Interpretations

1. The Forest as Transformation

Forests in medieval literature represent:

Places of moral testing

Encounters with fate

Internal struggle and revelation

Nastagio’s journey is both literal and personal.

2. Clothing and Nudity

The contrast between:

The richly dressed noblewomen

The nude punished woman

signals moral exposure and vulnerability.

3. Dogs as Agents of Justice

The black dogs symbolize relentless punishment and the inescapability of judgment.

4. The Marriage Scene

The final panel symbolizes:

The restoration of order

Family unity

The triumph of societal expectations over individual desires

Controversies Surrounding The Painting

Although admired for centuries, the series has sparked modern controversies.

A. Gender Dynamics and Violence Against Women

Today’s viewers often criticize:

The glorification of using terror and violence to coerce a woman into marriage

The depiction of the woman’s suffering as a moral “lesson”

The message that a woman’s refusal of love is punishable

Scholars debate whether Botticelli intended critique or simply illustrated a popular tale.

B. Wedding Gift Controversy

Modern audiences question why such violent scenes were considered appropriate wedding gifts. Historians explain that the paintings emphasized obedience and social order, ideas normalized at the time but unsettling now.

C. The Use of Female Nudity

Some find the nude, tortured woman objectifying or voyeuristic. Others argue the nudity symbolizes vulnerability and moral exposure.

What Do People Think About the Paintings Today?

Historical Opinion (15th–19th Century)

The series was admired for:

Storytelling skill

Beauty and elegance

Moral significance

Connection to Boccaccio, a beloved Florentine writer

The violent elements were rarely criticized.

Modern Opinion (20th–21st Century)

Public and scholarly opinion is more divided.

Admiration

Outstanding example of narrative Renaissance painting

Masterful technique and composition

Insight into Medici culture and marriage customs

Important literary adaptation

Criticism

Reinforcement of patriarchal values

Graphic violence against a woman

Use of fear to force marriage

Yet this debate has increased the series’ cultural relevance, making it a prime case study in discussions of art, power, gender, and ethics.

Where Are The Story of Nastagio degli Onesti Panels Located Today?

The four original panels are now separated:

Panel I – Prado Museum, Madrid

Panel II – Prado Museum, Madrid

Panel III – Museo del Prado (on loan or displayed separately)

Panel IV – Pucci Palace, Florence (privately owned but occasionally exhibited)

The first three belong to the Museo del Prado, which houses one of the world’s best Botticelli collections.

The fourth panel remains in Florence, connecting the painting to its original context.

Why This Painting Still Matters

The Story of Nastagio degli Onesti stands as one of the Renaissance’s greatest narrative cycles, beautiful, shocking, morally complex, and deeply revealing of its time.

It represents a world where art served not only aesthetic purposes but also social education, political messaging, and the reinforcement of cultural norms.

Whether admired for its craftsmanship or critiqued for its themes, Botticelli’s series continues to inspire conversation, reflection, and fascination over 500 years after it was painted.