Craquelure in Art: Meaning, Value, and Science Behind the Cracks

Craquelure, those delicate, web-like patterns of fine cracks that lace the surface of old artworks, has fascinated art lovers for centuries. At first glance, it may look like nothing more than signs of aging, but in reality, craquelure is rich with information. It reveals an artwork’s history, confirms authenticity, exposes environmental conditions, and can even increase the monetary value of a painting.

Craquelure in antique oil paintings refers to the intricate network of cracks that form on the painted surface as a result of aging, material behavior, and environmental exposure over long periods of time. These cracks are among the most recognizable visual characteristics of historical oil paintings and are often perceived by viewers as signs of authenticity and venerable age. Far from being merely cosmetic defects, craquelure embodies a complex intersection of chemistry, physics, artistic technique, and history. For conservators, art historians, and collectors, the study of these cracks provides critical insights into how an antique oil painting was made, how it has survived, and whether it is truly what it claims to be.

At the core of craquelure formation is the layered structure of an oil painting. Traditional antique oil paintings typically consist of a support, commonly a wooden panel in earlier periods or a stretched canvas in later ones, covered with a preparatory ground layer, followed by multiple layers of oil-based paint and often a final varnish. Each of these layers has distinct mechanical and chemical properties. Oil paint, for example, hardens through oxidation rather than evaporation, becoming increasingly brittle over decades and centuries. Meanwhile, supports such as wood and canvas continuously respond to changes in humidity and temperature by expanding and contracting. When these movements occur at different rates across layers, internal stress accumulates and is eventually released in the form of cracking.

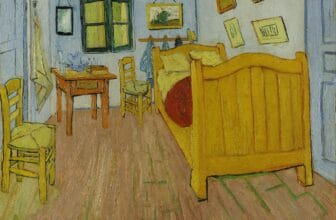

The patterns of craquelure in antique oil paintings are highly informative. On wooden panels, which were common in Northern European painting until the sixteenth century, cracks often appear as long, linear fissures aligned with the wood grain. These reflect the natural tendency of wood to expand and contract across, rather than along, the grain. Canvas paintings, more prevalent from the Renaissance onward, typically exhibit a more irregular, web-like craquelure pattern. The elasticity of the fabric support allows for multidirectional movement, producing a complex crack network that differs markedly from panel paintings. Such distinctions help specialists identify the original support even when it is no longer visible.

Craquelure also reveals much about an artist’s technique. One of the most important traditional principles of oil painting is “fat over lean,” which dictates that each successive paint layer should contain more oil than the one beneath it. When this rule is violated, such as when a lean, fast-drying layer is placed over a richer, slower-drying one, the upper layer may dry and harden first, leading to tension and cracking as the lower layer continues to move. This type of drying craquelure can appear relatively early in a painting’s life and is often characterized by sharp-edged, irregular cracks. In antique paintings, the presence and nature of such cracks can indicate whether the artist worked hastily, experimented with materials, or deviated from established workshop practices.

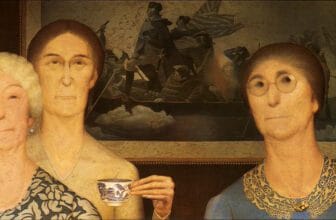

Beyond technique, craquelure carries significant meaning in the cultural understanding of antique oil paintings. For many audiences, cracks are inseparable from the aura of historical art. They signal endurance and survival, suggesting that the painting has witnessed centuries of human history. This perception is so deeply ingrained that paintings lacking craquelure are sometimes viewed with suspicion, even when they are genuinely old but exceptionally well preserved. Conversely, the desire for the appearance of age has led to the deliberate creation of artificial craquelure in later works and forgeries, underscoring how strongly cracks are associated with authenticity.

Because of this, craquelure plays a crucial role in art authentication. Conservators and technical art historians carefully examine crack patterns using magnification, raking light, and imaging technologies such as X-radiography and infrared reflectography. Natural age craquelure tends to be integrated with the paint structure, penetrating through multiple layers and exhibiting rounded edges softened by time. Artificially induced cracks, by contrast, often appear too regular, too superficial, or inconsistent with the materials claimed. The study of craquelure can therefore expose attempts at deception and help differentiate genuine antiques from later imitations.

Craquelure also functions as a historical record of a painting’s life beyond the studio. Environmental conditions such as fluctuating humidity, exposure to heat, or past restoration efforts can all influence crack formation. For example, paintings that have been rolled, relined, or subjected to excessive cleaning may display disrupted or widened cracks. In this sense, craquelure documents not only the moment of creation but also centuries of handling, display, neglect, and care. Each crack is a trace of interaction between the object and its environment.

From a conservation perspective, craquelure presents a delicate balance between preservation and respect for historical integrity. While stable craquelure is often left untreated, unstable cracks that lead to flaking or paint loss require intervention. Consolidation treatments may be used to secure lifting paint, but conservators generally avoid filling or disguising cracks unless absolutely necessary. The prevailing ethical view is that craquelure is part of the painting’s historical identity and should not be erased in pursuit of a falsely pristine appearance. In antique oil paintings, the cracks themselves have become integral to how the work is understood and valued.

The “secrets” behind the cracks extend to hidden artistic decisions. Craquelure patterns sometimes align with underlying compositional changes, known as pentimenti, where an artist altered figures or objects during the painting process. As paint layers age and crack, these hidden revisions can become more legible, offering insight into the artist’s creative process. In this way, craquelure acts as an unintentional revealer, bringing to light aspects of the painting that were once concealed.

Craquelure in Paintings: Causes, Consequences, and Connoisseurship

Craquelure, the network of fine cracks that develops on the surface of paintings, is one of the most recognizable signs of age in fine art. To the untrained eye, craquelure may appear to be simple damage. To conservators, historians, and collectors, however, it is a complex physical phenomenon that can reveal a painting’s materials, history, and authenticity. Whether craquelure detracts from or enhances a painting’s value depends on context, quality, and provenance. Understanding why craquelure occurs, how it is influenced by environmental factors, and how experts distinguish genuine aging from artificial cracking is essential for anyone engaged with historic or investment-grade artworks.

Why Craquelure Happens in Paintings

Craquelure occurs due to the natural aging and mechanical stresses within a painting’s layered structure. Most traditional paintings consist of several layers: a support (canvas, wood panel, or board), a ground or priming layer, paint layers, and often a varnish. Each of these materials responds differently to environmental conditions and the passage of time.

Oil paint, the most common medium in Western easel painting from the Renaissance onward, dries through oxidation rather than evaporation. This slow chemical process continues for decades, causing the paint film to become increasingly brittle. As the paint loses flexibility, it becomes less able to accommodate movement in the support beneath it.

Canvas expands and contracts with changes in humidity and temperature. Wooden panels may warp or split as they age. When the support moves and the paint layer cannot move with it, stress is released in the form of cracks. These cracks tend to follow characteristic patterns influenced by the artist’s technique, the thickness of the paint, the composition of pigments, and the preparation of the surface.

Does Craquelure Devalue a Painting or Increase Its Price?

Craquelure does not have a universal impact on value; its effect depends on context. In many cases, particularly for Old Master and early modern paintings, craquelure is expected and even desirable. A fine, stable craquelure pattern can serve as visual evidence of age and authenticity. Collectors and institutions often view it as part of the painting’s historical integrity.

However, excessive or unstable craquelure, especially when accompanied by flaking or paint loss, can negatively affect value. Structural instability increases conservation risk and future maintenance costs. In modern and contemporary works, where pristine surfaces are often integral to artistic intent, craquelure may significantly reduce market value.

In summary, craquelure can enhance value when it is consistent with the painting’s age, style, and condition expectations, but it can diminish value when it compromises structural integrity or contradicts the artist’s original intent.

Do Collectors Like Paintings With Craquelure?

Collector attitudes toward craquelure vary widely. Traditional collectors and institutions often accept craquelure as an inherent feature of historic paintings. For these buyers, the presence of authentic craquelure may reinforce confidence in the work’s age and originality.

Some collectors even find craquelure aesthetically appealing. The subtle web of cracks can add visual depth and texture, lending a sense of gravitas and historical presence that smooth, modern surfaces lack.

Conversely, collectors focused on contemporary art or decorative appeal may view craquelure as damage. In these markets, condition sensitivity is high, and even minor surface cracking can be a deterrent. Ultimately, collector preference aligns closely with the genre, period, and intended use of the artwork.

How Does Humidity Affect Craquelure?

Humidity is one of the most critical environmental factors influencing craquelure. Fluctuations in relative humidity cause organic materials, such as canvas, wood, and animal-glue grounds, to expand and contract. Repeated cycles of swelling and shrinking place mechanical stress on the paint layers.

High humidity can soften certain paint films and promote mold growth, weakening adhesion between layers. Low humidity, on the other hand, can cause materials to dry out and become brittle, increasing the likelihood of cracking.

Rapid or frequent humidity changes are particularly damaging. Museums and professional storage facilities therefore maintain strict climate control, typically aiming for a stable relative humidity around 45–55 percent. Poor environmental control is one of the most common causes of accelerated craquelure in privately held artworks.

Can Craquelure Be Fake?

Yes, craquelure can be artificially induced, and it has been used historically as a tool of forgery. Because genuine craquelure is often associated with age and authenticity, forgers attempt to replicate it to make newer paintings appear older.

Artificial craquelure can be created using a variety of methods, including the deliberate manipulation of paint drying times, the application of incompatible layers, mechanical stressing, or chemical treatments. Some modern commercial products are even designed to produce a “crackle” effect for decorative purposes.

While these techniques can create convincing surface patterns, fake craquelure often lacks the structural coherence and material logic of naturally aged paint films.

How Experts Detect Fake Craquelure

Art conservators and forensic specialists use a combination of visual analysis, scientific testing, and historical knowledge to distinguish genuine craquelure from artificial cracking.

Under magnification, authentic craquelure typically penetrates multiple layers in a consistent manner, whereas fake craquelure may be superficial or unnaturally uniform. The pattern of cracks should correspond logically to the support, paint thickness, and known practices of the purported period.

Advanced imaging techniques such as X-radiography, infrared reflectography, and ultraviolet fluorescence can reveal discrepancies between surface cracking and underlying layers. Chemical analysis of pigments and binders may also expose anachronistic materials incompatible with the claimed age of the work.

In short, while fake craquelure may deceive casual observers, it is difficult to sustain under rigorous expert examination.

Can Craquelure Be Repaired or Removed?

Craquelure itself cannot be truly “removed” without destroying the original paint layer. Because it is the result of structural aging, eliminating cracks would require replacing or fundamentally altering the paint film, an unacceptable intervention under modern conservation ethics.

What conservators can do is stabilize craquelure. Flaking or lifting paint can be re-adhered to prevent further loss. Surface coatings may be consolidated to improve cohesion, and environmental conditions can be optimized to slow future deterioration.

In some cases, minor visual compensation, such as retouching losses or reducing the visual impact of cracks, may be undertaken. These interventions are typically reversible and carefully documented. The goal of conservation is preservation and stabilization, not cosmetic perfection.

Craquelure is neither inherently a flaw nor an automatic asset. It is a natural consequence of time, materials, and environment, offering valuable insight into a painting’s history and condition. For collectors, conservators, and scholars, understanding craquelure is essential to informed judgment about authenticity, value, and care.

When stable and consistent with age, craquelure can enhance a painting’s credibility and character. When excessive or artificially induced, it raises red flags and conservation concerns. Ultimately, craquelure serves as a visible reminder that paintings are physical objects, subject to the laws of chemistry and physics as much as to the intentions of the artist.

Craquelure is far more than a network of cracks, it is a historical fingerprint, a scientific clue, a sign of authenticity, and often an aesthetic enhancement to a work of art. It forms naturally as materials age, expand, contract, and respond to the environment, and it varies widely depending on the artist’s methods, regional traditions, and the painting’s journey through time.

Collectors frequently appreciate natural craquelure because it confirms the artwork’s authenticity and age. In many cases, it increases a painting’s value. Only when craquelure becomes unstable or severe does it reduce the artwork’s desirability.

Craquelure is not limited to paintings; it appears on ceramics, lacquerware, furniture, and many other objects. It can be artificially created, but skilled analysis usually exposes such forgeries. Different types of craquelure, age, drying, varnish, panel, and regional patterns, tell experts a great deal about a painting’s origin, materials, and history.

Craquelure in antique oil paintings is a symptom of aging or deterioration. It is a rich source of information about materials, techniques, authenticity, and historical experience. The cracks that traverse these surfaces are the visible outcome of centuries of chemical reactions, mechanical stresses, and human interaction. They shape how we perceive antique oil paintings, influencing judgments of beauty, value, and truth. By studying craquelure closely, we gain access to the hidden narratives embedded within these works, narratives that speak of artistic intention, material vulnerability, and the enduring passage of time.