Autograph Works vs. Workshop Paintings

The High Stakes of Authorship in the Old Master Market

In the world of Old Master painting, two works can appear almost identical to the untrained eye yet exist in wildly different financial and cultural realities. A composition repeated by a master’s studio may hang side-by-side with the artist’s fully autograph version, sharing nearly the same outlines, colors, and iconographic elements, and yet the market treats them as entirely separate species. One might draw museum curators, private foundations, and elite collectors into fierce competition, ultimately selling for tens of millions. The other may circulate at modest auction levels, valued at a fraction of its near-twin.

The reason for this stark divide is not merely appearance or subject matter but authorship. The Old Master market is built on a hierarchy of authorship unlike anything in contemporary collecting. An autograph painting, created entirely by the artist’s own hand, stands at the top of this hierarchy and defines the true pinnacle of value. All other versions, whether produced with the master’s guidance, partially executed by his assistants, or entirely crafted by his workshop, occupy lower tiers that dramatically alter the financial and scholarly meaning of the work.

The Essence of an Autograph Painting

An autograph work is far more than a painting in the master’s style. It is the purest record of the artist’s creative intellect and technical command. Every stroke in an autograph painting bears evidence of the artist’s direct decisions. Every adjustment, whether dramatic or subtle, represents a moment of reconsideration or experimentation. These touches embody the artist’s own search for form, emotion, and light.

Collectors prize autograph paintings, not merely because they are rare or prestigious, but because they contain the profound human trace of creativity. There is no intermediary in an autograph work; the painting is a direct transmission from the artist’s mind to the viewer’s experience. Many Old Masters produced astonishingly few paintings entirely by their own hand. Vermeer is believed to have left no more than thirty-five works. Raphael’s fully autograph pieces number perhaps under one hundred. Caravaggio’s surviving oeuvre is similarly limited. Scarcity magnifies desirability, and desirability fuels bidding. This is why autograph works routinely achieve prices that seem to exist in another universe compared to even the finest studio versions.

What Workshop Paintings Really Represent

Workshop paintings occupy a more ambiguous territory. They are not forgeries, nor are they modern attempts to imitate. Rather, they are legitimate products of the artist’s studio, created in the environment where the master taught, designed compositions, supervised technique, and approved finished works. During the Renaissance and Baroque periods, studios functioned as highly organized enterprises. Apprentices trained under strict systems, learning to emulate the master’s style with remarkable fidelity. Senior assistants could execute large portions of a composition, while the master reserved the crucial figure or the final touches for himself.

These practices were not only accepted but expected. Patrons understood that the prestige of a workshop carried value, even if the master himself did not paint every inch. Yet in today’s collecting world, where connoisseurship and authorship are paramount, workshop paintings occupy a secondary tier. They can be beautiful, historically important, and sometimes astonishingly skilled, but the absence of full authorship inevitably affects price.

The disparity can be breathtaking. A Rubens mythological autograph painting may command tens of millions, while a workshop version or variant might change hands for under two million. A Titian Venus executed with his personal touch draws museum-level bidding, whereas a similar composition repeated by his studio may find buyers in the mid-six-figure range. Even a highly accomplished workshop Rembrandt portrait seldom approaches the value of a fully autograph example. The divide between these categories, millions versus thousands, demonstrates the enormous premium placed on the master’s personal involvement.

The Hidden Economics of Autograph Versus Workshop Works

The market’s valuation is grounded in a simple but powerful economic principle: the closer a painting comes to the artist’s actual hand, the more valuable it becomes. Autograph paintings represent direct creative origin. Workshop pieces represent proximity to that origin. Both possess historical significance, but one embodies authorship, while the other represents production.

This hierarchy creates exponential shifts in price, not incremental ones. The presence of the master’s hand in key passages, especially the face, hands, or final highlights, may elevate a painting dramatically, even if most of it was executed in the studio. Conversely, a painting executed entirely by assistants but following the master’s cartoon or drawing may fall sharply in value despite its visual beauty. The art market is fundamentally an attribution market. Beauty matters. Condition matters. Rarity matters. But authorship is the gravitational force around which everything else revolves.

This is also why reattributions can cause seismic effects. A painting once considered a studio work may suddenly surge in value if new evidence reveals it to be autograph. Likewise, a painting long believed to be autograph may fall out of favor if scholars determine that the studio played a more dominant role. These shifts are not merely academic. They can alter values by millions of dollars in an instant.

How Experts Identify Autograph Works

Determining authorship is a delicate dance between science, scholarship, and connoisseurial intuition. Experts begin by examining the brushwork, which often reveals minute characteristics of the artist’s personal style. A master’s brushwork tends to show a unique rhythm, sensitivity, and confidence that cannot be easily mimicked. Rembrandt’s handling of shadowed flesh has a depth and softness that assistants rarely achieved. Rubens’s energetic, sweeping strokes possess a muscularity that his studio could echo but seldom replicate. Titian’s late technique, with its shimmering layers of broken color, reflects an artistic freedom that assistants could follow in theory but not in spirit.

Underdrawing plays a central role in attribution. Infrared reflectography often reveals hidden lines, sketches, and alterations beneath the paint. Masters frequently revised their compositions during the creative process, adjusting the tilt of a head, reshaping a hand, or modifying the direction of light. These revisions, known as pentimenti, offer compelling evidence of the master’s personal involvement because assistants rarely modified a composition they were instructed to follow. Their task was to replicate, not to reimagine.

Scientific analysis contributes additional layers of insight. X-rays can reveal earlier compositions beneath the surface, shedding light on the artist’s working habits. Pigment samples may show mixtures consistent with the master’s known palette. Dendrochronology can confirm whether a wooden panel dates to the correct period. Even the ground layers, foundations of the painting, may correspond to known practices in the master’s workshop, helping scholars identify whether the work is autograph, partially autograph, or entirely studio-made.

Provenance research is equally crucial. Paintings with clear, early ownership histories often hold more weight in attribution discussions. Works recorded in seventeenth- or eighteenth-century inventories, letters, or travelogues offer a stronger claim to authenticity. Conversely, paintings that appear only in modern documentation require more rigorous technical scrutiny. Experts often compare a suspect work with confirmed autograph examples, looking for consistent patterns in anatomy, drapery, lighting, and psychological expression.

Yet, even with an arsenal of scientific tools and scholarly insight, the connoisseur’s eye remains indispensable. Experienced scholars develop an intimate awareness of an artist’s hand, gained through decades of studying originals. They notice nuances invisible to casual viewers: the softness of a shadow, the boldness of a contour, the expressive tension of a gesture. The emotional resonance of a master’s touch is difficult to quantify, but unmistakable when encountered.

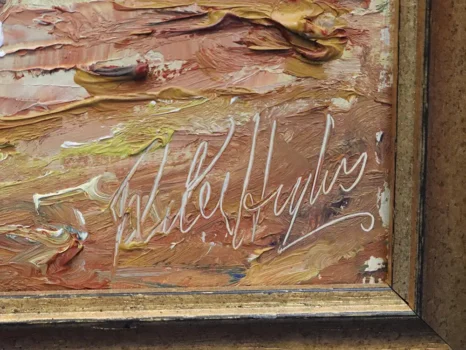

Why Signatures and Artist Proofs Do Not Determine Value in Paintings

Collectors often assume that signatures guarantee authenticity, but in the Old Master field, signatures are not the definitive markers they are in modern or contemporary art. Many artists did not sign their works consistently. Some signed only commissions, while others rarely signed at all. Workshop assistants sometimes added signatures to studio paintings, and later owners occasionally introduced signatures to elevate a work’s status. As a result, a signature can be authentic, misleading, or entirely irrelevant. Scholars rely on technical and stylistic evidence rather than painted signatures to establish authorship.

The topic of artist proofs arises frequently among new collectors, especially those familiar with modern printmaking. In the world of prints, artist proofs are indeed special. They represent impressions reserved for the artist’s private use and may exhibit subtle differences in tone or paper. They usually command a modest premium because they are scarcer and have a closer conceptual link to the artist. However, this concept does not translate to Old Master painting. Paintings do not have editions, and the idea of an artist proof simply does not apply. What matters in painting is the extent of the master’s physical involvement, not the presence of a signature or proof mark.

Why Workshop Paintings Are Becoming Increasingly Desirable

Despite their secondary position relative to autograph works, workshop paintings have experienced renewed collector interest. The price gap between autograph and workshop works has widened so dramatically that workshop paintings now offer exceptional value. They bring the beauty, history, and cultural prestige of Old Master art into a far more accessible price range. Many workshops produced works of astonishing quality, particularly those led by Rubens, whose studio was renowned for excellence. Scholars often regard his workshop pieces as among the finest collaborative artworks of the Baroque era.

Collectors also appreciate the narrative dimension of workshop paintings. To own a work produced in the same studio, under the same master, within the same artistic environment is to hold a fragment of art history itself. These paintings serve as living witnesses to the master’s influence, teaching methods, and artistic legacy. They offer collectors an intimate connection to the world of the artist without the financial demands of autograph ownership.

Building a Collection with Authorship in Mind

Collectors navigating the Old Master market must understand that every acquisition represents a layered decision involving authorship, quality, condition, provenance, and scholarly consensus. Autograph paintings are the crown jewels of any collection and provide unmatched investment potential. Yet even within the autograph category, collectors must evaluate the quality of execution. A fully autograph but relatively uninspired painting may hold less long-term appeal than a partially autograph work of remarkable beauty and emotional resonance.

Workshop paintings also deserve careful consideration. The most compelling examples, particularly those with evidence of the master’s final touches, can be both aesthetically rewarding and financially sound. Their value tends to remain stable because they fill a desirable middle tier between the stratospheric price levels of autograph works and the more modest levels of later copies and imitations.

Collectors must also understand the fluid nature of attribution. Changes in scholarly opinion can elevate or diminish a painting’s status. These decisions are not arbitrary. They result from new research, fresh technical analysis, or discoveries about the artist’s working habits. The possibility of future reattribution introduces both excitement and risk, and this dynamic is one of the elements that makes Old Master collecting uniquely rewarding.

Why Authorship Remains the Ultimate Measure of Value

The Old Master market revolves around one fundamental truth: authorship is the most powerful determinant of value. It is the reason two nearly identical paintings can sell for radically different sums. It is the reason collectors pursue autograph works with such intensity and why museums build their collections around verifiable masterpieces. Authorship embodies creativity, rarity, prestige, and artistic legacy. It allows collectors not only to own a beautiful object but to hold a direct piece of cultural history.

Workshop paintings, while not autograph, remain precious links to the creative world of the master, offering collectors a chance to engage with the past in visually and historically meaningful ways. Yet nothing replaces the thrill of standing before a canvas shaped entirely by the artist’s hand. In that moment, the centuries collapse, and the viewer encounters the artist’s mind in its purest form.

This is why millions are spent on autograph masterpieces, and why workshop versions, however beautiful, remain far more accessible. In the world of Old Masters, the value of a painting is not determined solely by what it shows, but by who touched it, who shaped it, and who, ultimately, brought it into existence. image/ invaluable