The Untold Story Behind the World’s Most Valuable Antique Art

Why the Greatest Antique Art Is Never Just About Beauty

The most valuable antique artworks in the world are often described in terms of price, provenance, and prestige. Auction headlines focus on numbers, museums emphasize authorship and condition, and collectors speak in the language of rarity. Yet beneath these surface narratives lies a deeper truth that seasoned collectors come to understand over time: value in antique art is inseparable from story. Paintings, sculptures, manuscripts, and decorative masterpieces that command extraordinary sums do so not merely because they are old or beautiful, but because they have endured extraordinary journeys through history.

Antique artworks survive wars, religious upheaval, regime changes, inheritance disputes, fires, neglect, theft, and deliberate destruction. Many were nearly lost forever. Others were misunderstood for centuries, dismissed as workshop copies or decorative objects before scholarship restored their true identity. Some were instruments of political power, others intimate possessions never meant for public display. These hidden narratives shape how collectors, institutions, and markets assign meaning and value today.

For art collectors, understanding these untold stories is not an academic luxury. It is a practical advantage. Knowledge of an object’s deeper history sharpens judgment, informs acquisition strategy, and provides context that protects against inflated claims or incomplete narratives. This guide explores ten of the world’s most valuable antique artworks through the lens of their lesser-known histories, revealing how myth, scholarship, chance, and human ambition transformed fragile objects into cultural icons.

1. Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi: From Overpainted Ruin to Global Obsession

Few artworks illustrate the power of narrative more vividly than Salvator Mundi. Painted around 1500, the image of Christ blessing the world was long considered a workshop piece or later copy. For centuries it passed quietly through royal collections, was damaged, heavily overpainted, and eventually sold in the twentieth century for a modest sum, stripped of any connection to Leonardo da Vinci.

Its transformation into the most expensive painting ever sold was not the result of sudden discovery, but of painstaking restoration, controversial scholarship, and strategic storytelling. Layers of later paint concealed subtle features associated with Leonardo’s hand, including the enigmatic treatment of the orb and the soft modeling of Christ’s face. As conservators removed centuries of alteration, scholars debated fiercely whether the surviving passages justified full attribution.

It’s not about authorship, but about how uncertainty itself fueled value. The ambiguity surrounding Salvator Mundi created a perfect storm of intrigue, allowing collectors, dealers, and institutions to project meaning onto the work. Its price reflected not consensus, but the extraordinary cultural capital of owning the most debated painting in the world. For collectors, it stands as a reminder that in the uppermost tier of antique art, narrative tension can be as powerful as historical certainty.

2. The Mona Lisa: A Private Portrait That Became a Political Icon

Today the Mona Lisa is synonymous with artistic greatness, yet its ascent to global fame was neither immediate nor inevitable. For centuries after Leonardo’s death, the painting remained a relatively modest court treasure, admired by connoisseurs but unknown to the wider public. Its true transformation began not in a studio or salon, but with theft.

In 1911, the painting was stolen from the Louvre by an Italian handyman who believed it should be returned to Italy. The ensuing international scandal turned the Mona Lisa into front-page news across continents. Reproductions circulated widely, public fascination exploded, and the painting’s identity shifted from Renaissance portrait to global symbol.

It is often overlook how modern fame reshaped historical value retroactively. The Mona Lisa was not created as a masterpiece destined for universal recognition. It became one through modern media, nationalism, and spectacle. Its story reveals how external forces beyond artistic merit can elevate an antique artwork into a cultural monument whose value transcends market calculation.

3. The Ghent Altarpiece: Survival Through Iconoclasm and War

The Ghent Altarpiece by Jan and Hubert van Eyck is one of the most valuable and influential works of Northern Renaissance art, not only for its technical brilliance, but for its improbable survival. Completed in 1432, the altarpiece has been stolen, dismembered, hidden, looted, and targeted repeatedly across centuries.

During periods of religious iconoclasm, panels were hidden to prevent destruction. Napoleon’s armies seized sections for the Louvre. Nazi forces later targeted the altarpiece as part of a larger campaign to appropriate European cultural heritage. Its recovery after World War II, hidden deep within an Austrian salt mine, cemented its status as a symbol of cultural resilience.

A story of trauma. Each historical crisis added layers of meaning, turning the altarpiece into a witness to European conflict. For collectors, this illustrates how survival itself becomes a form of provenance, imbuing antique artworks with moral and historical authority that extends far beyond aesthetics.

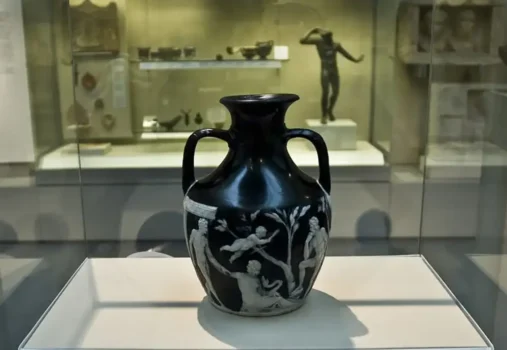

4. The Portland Vase: Fragility, Fame, and the Birth of Museum Security

The Portland Vase, a Roman cameo glass masterpiece from the first century BCE, is one of the most valuable objects of classical antiquity. Its beauty lies in its delicate white figures floating against deep blue glass, a technical feat never fully replicated. Yet its modern story is defined by destruction.

In 1845, while on display at the British Museum, the vase was smashed into hundreds of pieces by a disturbed visitor. The act shocked Victorian society and exposed the vulnerability of public collections. Its painstaking reconstruction, followed by later restorations using modern technology, transformed the vase into a symbol of both loss and recovery.

Collectors often focus on ancient origin, but the Portland Vase’s value is inseparable from its modern history. It reshaped museum practices, influenced glassmakers for generations, and demonstrated that damage, when documented and addressed responsibly, can become part of an object’s enduring narrative rather than a fatal flaw.

5. Michelangelo’s David: A Political Statement Disguised as Sculpture

Michelangelo’s David is celebrated as an idealized nude and technical triumph, but its original meaning was deeply political. Carved from a flawed block of marble rejected by other sculptors, the statue was commissioned by the Florentine Republic as a symbol of defiance against tyranny.

Placed outside the Palazzo della Signoria, David represented civic virtue and resistance, not biblical piety. Its gaze and posture were intended to confront political enemies, both internal and external. Over time, this charged symbolism softened as the sculpture was absorbed into the canon of universal beauty.

A story of how political intent fades while form endures. Antique artworks often outlive their original purpose, allowing later generations to reinterpret them. Understanding those original contexts adds depth to appreciation and guards against simplistic readings based solely on aesthetics.

6. The Arnolfini Portrait: A Legal Document in Paint

Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait is frequently admired for its realism and symbolic detail, but its deeper function remains underappreciated. Many scholars believe the painting served as a visual legal record, possibly documenting a marriage or contractual agreement.

In an era when written contracts were less standardized, paintings could serve as witnesses. The artist’s signature, boldly stating that van Eyck was present, suggests a role beyond mere depiction. Objects within the room reinforce themes of fidelity, wealth, and legitimacy.

This reveals how antique artworks often operated within social systems now unfamiliar to modern viewers. Paintings were not always decorative luxuries; they could function as legal instruments, moral statements, or political tools. Such multifunctionality adds layers of value that transcend visual appeal.

7. The Bayeux Tapestry: Propaganda Woven in Thread

The Bayeux Tapestry, though technically an embroidery, ranks among the most valuable narrative artworks of the medieval world. Stretching nearly seventy meters, it recounts the Norman Conquest of England with remarkable detail and bias.

Its untold story lies in its function as propaganda. The tapestry presents a carefully curated version of events that legitimized Norman rule. Scenes are omitted, emphasized, or framed to shape historical memory. For centuries, viewers accepted its narrative as fact, demonstrating the power of visual storytelling.

Collectors of antique art benefit from recognizing how art shapes history rather than merely recording it. Objects like the Bayeux Tapestry remind us that value can arise from influence as much as from craftsmanship.

8. Raphael’s School of Athens: Philosophy as Power

Raphael’s School of Athens is often celebrated as a harmonious gathering of ancient philosophers, yet its creation was embedded in Vatican politics. Commissioned by Pope Julius II, the fresco asserted the Church’s intellectual authority by aligning Christian leadership with classical wisdom.

The identities of figures within the fresco subtly reference contemporary artists and thinkers, embedding Renaissance rivalries and alliances within an idealized past. The painting thus operates on multiple levels: philosophical, political, and personal.

9. Caravaggio’s Judith Beheading Holofernes

Caravaggio’s Judith Beheading Holofernes and the Sutton Hoo helmet belong to radically different worlds, one born in the violent streets and candlelit studios of Baroque Rome, the other unearthed from the soil of early medieval England, yet both objects share an untold story shaped by power, fear, and the deliberate construction of meaning. Each is more than an artwork or artifact; each is a calculated statement about authority, violence, and memory.

Caravaggio painted Judith Beheading Holofernes around 1598–1599, at a moment when his own life was already entangled with danger. Rome was a city of duels, tavern brawls, and judicial executions carried out in public squares. Caravaggio moved within this volatile environment, absorbing its brutality and reflecting it back with unprecedented realism. The untold story of Judith lies not only in its biblical subject, but in how closely it mirrors the painter’s psychological state. Unlike earlier Renaissance depictions, which often idealized Judith as a serene heroine, Caravaggio presents the act of violence as awkward, tense, and disturbingly intimate. Judith’s arm is not confidently raised; it hesitates. Her face shows revulsion rather than triumph. The blood does not flow symbolically, it spurts, real and unavoidable.

Many scholars believe Caravaggio used live models drawn from Rome’s margins: prostitutes, laborers, criminals. The severed head of Holofernes has long been suspected to resemble Caravaggio himself, a grim act of self-insertion that turns the painting into a form of confession. At the time, Caravaggio was increasingly at odds with authority, accumulating charges for assault and illegal weapon possession. The painting may reflect an obsession with justice and punishment, a subconscious rehearsal of his own violent fate. Within a decade, he would kill a man and flee Rome as a fugitive. In this light, Judith Beheading Holofernes becomes less a moral lesson and more a meditation on the thin line between righteous violence and criminal bloodshed, a line Caravaggio himself was already crossing.

10. The Sutton Hoo Helmet

The Sutton Hoo helmet, by contrast, tells its untold story through silence rather than shock. Buried in the early seventh century within an Anglo-Saxon ship burial in Suffolk, the helmet was shattered into hundreds of fragments before its discovery in 1939. For decades, its true appearance and meaning had to be reconstructed through patient scholarship. What emerged was not merely a piece of armor, but a carefully designed political object. The helmet’s face mask, eyebrows, and nose combine to form the image of a dragon in flight, a visual riddle meant to transform the wearer into something more than human. When worn, the king’s face disappeared, replaced by a mythic creature associated with protection, terror, and divine authority.

The untold story lies in how the helmet functioned not primarily in battle, but in ritual. Its delicate construction suggests it was too precious for constant warfare. Instead, it likely appeared during ceremonies, assemblies, and diplomatic encounters, where visual dominance mattered more than physical combat. In a largely illiterate society, power was communicated through spectacle. The Sutton Hoo helmet turned kingship into theater, projecting the ruler as both warrior and supernatural guardian. Its burial within a ship, a symbol of journey and transition, suggests an understanding of death not as an end, but as a continuation of status beyond the grave.

Together, Caravaggio’s Judith and the Sutton Hoo helmet reveal how art and objects serve as instruments of power shaped by fear. One confronts violence directly, forcing the viewer to witness its cost. The other conceals violence behind symbolism, transforming force into authority. Their untold stories remind us that great works do not merely reflect their time; they encode the anxieties, ambitions, and inner conflicts of the societies, and individuals, that created them. image/ sylcreate