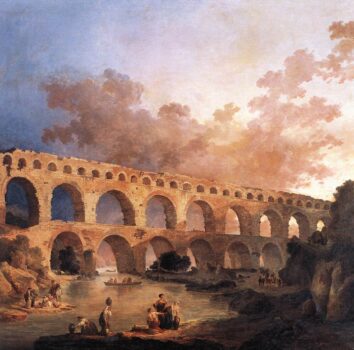

The Pont du Gard Painting by Hubert Robert

Hubert Robert, a master of 18th-century French landscape painting, is celebrated for his romanticized views of ruins and his ability to breathe life into antiquity through brush and imagination. Among his many revered works, The Pont du Gard stands as a sublime blend of natural beauty, architectural majesty, and contemplative ruin. This painting is more than a picturesque portrayal of a Roman aqueduct, it is a layered meditation on time, decay, and the enduring power of human ingenuity. This essay explores the full scope of The Pont du Gard painting by Hubert Robert: its visual elements, symbolism, artistic style, and enduring relevance, while uncovering the story it tells about civilization, history, and artistic vision.

Before diving into the painting itself, it is crucial to understand the subject that captivated Hubert Robert, the actual Pont du Gard. Located in the South of France, near Nîmes, the Pont du Gard is a Roman aqueduct bridge built in the first century AD. Standing nearly 50 meters tall and extending over 275 meters across the Gardon River, this UNESCO World Heritage Site is an extraordinary example of Roman engineering.

Its purpose was utilitarian: to transport water across a valley, supplying the Roman city of Nemausus (modern-day Nîmes). However, its aesthetic and architectural grandeur have long elevated it beyond mere function, turning it into a symbol of Roman imperial power, technological prowess, and harmonious design. By the 18th century, the structure was already a revered ruin, drawing artists, poets, and thinkers, including Hubert Robert.

Hubert Robert and the Romance of Ruins

Hubert Robert (1733–1808), often referred to as “Robert des Ruines,” was a master at combining real architectural forms with imaginative settings. After studying in Rome and absorbing the grandeur of classical antiquity, Robert returned to France with a deep appreciation for the interplay between civilization and decay.

He did not merely paint what he saw; he painted what he imagined the ruins might become, or what they had been. This poetic license allowed him to transform actual sites like the Pont du Gard into timeless reflections on human ambition, transience, and nature’s slow reclamation of man-made wonders.

What Is Happening in The Pont du Gard?

In his rendition of The Pont du Gard, Hubert Robert portrays the aqueduct in a sunlit, pastoral setting. The massive arches stretch across the composition, dominating the scene with their solemn grandeur. Yet rather than presenting the structure as a cold, lifeless ruin, Robert fills the landscape with human activity.

In the foreground, we see washerwomen and peasants going about their daily routines near the river. Shepherds lead their flocks. A few figures rest in the shade of trees. The natural setting is lush and green, with the shimmering waters of the Gardon flowing gently beneath the ancient arches.

What stands out is the coexistence of ancient monumentality and ordinary life. There is no spectacle of drama or conflict; instead, the painting evokes a serene continuity between past and present, where life moves gently under the shadow of history.

Symbolism and Interpretation

1. The Ruin as a Symbol of Time and Memory

The Pont du Gard, already centuries old at the time of Robert’s painting, symbolizes the passage of time. Ruins in Robert’s art often serve as a metaphor for the decline of civilizations and the cyclical nature of history. By presenting the aqueduct in partial ruin, he emphasizes not loss but endurance. The structure stands resilient, even in decay, much like human memory itself, weathered but not erased.

In this way, the aqueduct becomes a canvas of memory, carrying the ghosts of Roman engineers, medieval travelers, and Enlightenment thinkers alike. Robert invites us to contemplate the layers of time embedded in stone.

2. The Beauty of Nature and Human Achievement

Rather than depicting nature as destructive or overpowering, Robert shows it harmonizing with the built environment. Ivy and foliage wrap gently around the stones, water flows steadily, and trees frame the scene without obscuring the monument. This is an Enlightenment-era vision of balance, where reason (embodied by Roman architecture) and nature (the pastoral landscape) are not at odds, but in conversation.

It suggests a philosophical worldview in which humanity is capable of greatness when working in concert with the natural world.

3. The Everyday and the Eternal

By populating the foreground with everyday people, peasants, shepherds, women washing clothes, Robert brings an earthy humanity to the grandeur of the setting. These figures are not overwhelmed by the monument; they coexist with it. Their presence suggests that life continues, regardless of the empires that rise and fall.

This juxtaposition elevates the ordinary to the level of the epic. In the grand narrative of civilization, it is not just emperors and architects who matter, but also those who live quietly in the shadows of their legacies.

4. Ruins as Sites of Reflection

During the 18th century, ruins were seen not merely as picturesque but as deeply philosophical. They inspired thoughts about mortality, legacy, and the nature of progress. Hubert Robert’s painting fits squarely within this tradition. The Pont du Gard, seen through Robert’s eyes, becomes a contemplative space. It asks viewers to consider their place in history and the transient nature of human achievements.

Artistic Style: What Type of Art Is It?

The Pont du Gard belongs to the genre of veduta and capriccio, both of which were popular in Robert’s time.

Veduta refers to a detailed, largely accurate depiction of a landscape or cityscape.

Capriccio involves a more imaginative or fantastical arrangement of architectural elements, often combining real and fictional ruins.

Robert often blended these two approaches. In The Pont du Gard, the aqueduct itself is faithfully rendered, but the surrounding elements, the pastoral idealism, the balanced harmony of human and nature, are filtered through his romantic imagination.

Stylistically, the painting is rooted in neoclassicism, with its admiration for antiquity, symmetry, and rational structure. Yet it also carries early hints of romanticism, especially in its emotive atmosphere and its preoccupation with ruins and the sublime.

Robert’s brushwork is loose but controlled, his palette warm and sun-dappled. He draws the viewer’s eye to the monumental structure but never loses sight of the human scale.

Where Is The Pont du Gard Painting Located Today?

Several versions and studies of The Pont du Gard by Hubert Robert exist, as he frequently revisited the theme of ruins in different formats. One of the most recognized versions of this painting is held by the Musée du Louvre in Paris, France. The Louvre, which houses many of Robert’s works, offers a fitting home for this meditation on classical legacy and Enlightenment ideals.

In addition to the Louvre, other studies or sketches related to the Pont du Gard theme by Robert may be found in various European collections, including the Hermitage Museum in Russia and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, which hold works either by Robert or inspired by his ruin motifs.

The Enduring Power of Hubert Robert’s Pont du Gard

Hubert Robert’s Pont du Gard is a beautiful landscape, it is a visual essay on civilization, memory, and the human condition. Through this painting, Robert blends history and imagination, permanence and transience, architecture and nature. His depiction of the aqueduct is not just a documentation of a Roman marvel but an interpretation of what it means for humanity to create, to endure, and to be forgotten.

By positioning everyday life against the backdrop of monumental ruins, Robert challenges the viewer to think about legacy, not as a grand declaration, but as something woven into the quiet moments of daily existence. The washerwoman beneath the Roman arch becomes as important as the stone engineer who designed it. In this way, Robert democratizes history through art.

Ultimately, The Pont du Gard remains a masterwork not only for its technical skill but for its emotional and philosophical resonance. It speaks across centuries, reminding us that while our empires may crumble, the beauty we create, and the lives we live in their shadows, can still inspire awe, reflection, and reverence.