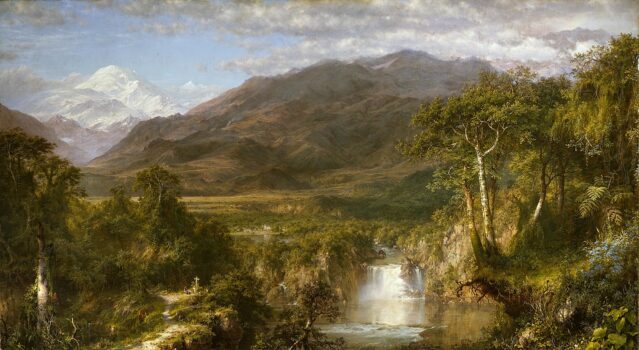

The Heart of the Andes by Frederic Edwin Church

In the vast history of American art history, few paintings have achieved the grandeur, reverence, and technical brilliance of The Heart of the Andes (1859) by Frederic Edwin Church. More than just a landscape, this monumental canvas is a poetic and spiritual meditation on the natural world. It encapsulates the awe-inspiring beauty of South America, channels scientific and theological inquiry, and invites viewers to contemplate their place in the universe.

This story takes a deep dive into the genesis, symbolism, interpretation, and lasting significance of The Heart of the Andes, examining how this artwork became an icon of the Hudson River School and a profound expression of 19th-century American thought.

What Is The Heart of the Andes All About?

At its core, The Heart of the Andes is a sweeping landscape that captures an imagined yet highly detailed composite of the South American Andes, inspired by Church’s travels in Colombia and Ecuador. It is not a single place, but rather a panoramic vision that blends various real locations into one harmonious and hyperreal scene.

The painting is about majesty, of both nature and divinity. Church did not merely set out to depict scenery; he sought to evoke the sublime, that blend of beauty and terror that philosophers like Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant had described in the 18th century. The painting offers a contemplative space, one where the viewer can spiritually and intellectually engage with nature’s vastness and intricacy.

Who Was Frederic Edwin Church and How Was the Painting Created?

Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900) was one of the leading figures of the Hudson River School, a group of American landscape painters influenced by Romanticism and characterized by their idealized, often spiritualized, depictions of the natural world.

Church was a protégé of Thomas Cole, the founder of the Hudson River School. Under Cole’s tutelage, Church developed a meticulous technique and a belief in the moral power of landscape art. He later distinguished himself by combining scientific observation with romantic grandeur, drawing inspiration from naturalists like Alexander von Humboldt.

The Journey Behind the Painting

The roots of The Heart of the Andes lie in Church’s expeditions to South America in 1853 and 1857. These journeys were inspired by Humboldt’s seminal book Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of America, which called for artists and scientists to explore and document the natural riches of the New World.

Church traveled with sketchbooks, watercolors, and journals, documenting everything from volcanoes to flora and fauna. He visited Mount Chimborazo, the Ecuadorian Amazon, and the Magdalena River valley. Though he painted The Heart of the Andes in his New York studio, the scenes depicted are painstakingly drawn from his real-life studies. He spent months arranging these elements into a single, cohesive vision that would evoke the totality of the Andean landscape.

The Final Work

Completed in 1859, the oil painting measures nearly 10 feet wide by 5 feet high (66 1/8 × 119 1/4 inches). It is painted on canvas, rendered with breathtaking detail and precision. Church used a fine brush to achieve botanical accuracy and employed layers of glaze to add depth and atmosphere.

When it was first exhibited in New York City, the painting was displayed alone in a darkened room with theatrical lighting, flanked by curtains and surrounded by palm fronds to mimic a window into nature itself. Spectators paid 25 cents to view it, more than a museum admission at the time, and were provided with opera glasses to inspect its details. The show was a sensation, and the painting was hailed as a national masterpiece.

What Is Happening in the Painting?

Though at first glance The Heart of the Andes appears to be a tranquil landscape, closer inspection reveals a complex and dynamic scene.

Foreground

The foreground features a lush, tropical setting: waterfalls cascade down mossy rocks; vibrant plants, meticulously rendered, frame a clear pond; butterflies flit among the leaves. A cross and a small church can be seen in the midground, near a cluster of people walking along a trail. This small yet spiritually resonant human presence serves to ground the scene and emphasize the harmony between mankind and nature.

Middle Ground

The landscape rises to reveal cultivated fields, a winding river, and a collection of modest thatched-roof homes, suggesting the presence of a small Andean village. The vegetation shifts from tropical to temperate, reflecting Church’s accurate depiction of altitudinal ecosystems.

Background

In the distance loom the majestic, snow-capped Andes, including Mount Chimborazo. The peaks ascend into the heavens, bathed in an ethereal light. Clouds and atmospheric haze add to the sense of depth and transcendence.

The journey from the lush foreground to the sublime mountains forms a vertical axis of spiritual ascent, what Humboldt described as the “unity of nature,” in which all elements, from microscopic to massive, are interlinked.

Symbolism and Interpretation

Church was a deeply intellectual and spiritual painter, and The Heart of the Andes abounds with symbolism. Though Church did not provide a written explanation of the painting, viewers have long interpreted its elements through the lenses of religion, science, and Romanticism.

1. A Pantheistic Landscape

The painting suggests that nature is a manifestation of the divine. The positioning of the church in the midground, barely visible amid the grandeur of nature, implies that God’s presence is most profoundly felt not in manmade structures but in the natural world itself. This pantheistic idea was common among American Transcendentalists like Emerson and Thoreau, who saw nature as sacred and spiritually instructive.

2. A Scientific Vision

Church was heavily influenced by Humboldt, who championed the empirical study of nature alongside its aesthetic appreciation. The painting functions almost like a scientific illustration, displaying ecological zones as they might appear at different altitudes, from jungle to tundra to alpine. The variety of flora and fauna is rendered with botanical precision, echoing Humboldt’s conviction that art should educate as well as inspire.

3. Manifest Destiny and American Exceptionalism

Although set in South America, the painting subtly echoes the American ideology of Manifest Destiny. The landscape is ordered, lush, and seemingly unspoiled, reflecting the idea that nature is a benevolent force awaiting harmonious human engagement. The tiny figures trekking through the terrain hint at man’s respectful exploration of God’s creation, a metaphor for the American spirit of discovery and progress.

4. Life, Death, and Transcendence

The cross in the foreground and the distant, soaring mountains can be interpreted as symbols of mortality and the soul’s journey toward the divine. The painting evokes a sense of timelessness and continuity, life unfolding in the valley, death memorialized by the cross, and eternity represented by the mountains and sky.

What Type of Art Is It?

The Heart of the Andes is a prime example of Hudson River School painting, a style that combines meticulous realism with romantic idealism. It is part of the Luminist movement, which emphasized the effects of light and atmosphere, and sought to convey a spiritual experience through landscape.

Church’s use of light in this painting is particularly noteworthy. The entire scene is suffused with a golden, almost supernatural glow. Light filters through clouds, glints off water, and suffuses foliage with vibrancy. This Luminist quality serves both an aesthetic and symbolic function: it heightens realism while reinforcing the divine presence within nature.

When The Heart of the Andes debuted in 1859, it was a blockbuster. Thousands of people paid to see it. Writers, artists, scientists, and laypeople alike were moved by its grandeur. It was considered a national treasure, comparable to the work of European Old Masters.

Mark Twain, after viewing the painting, wrote:

“You will never get tired of looking at it… You cannot look at it, the mind is instantly thrown into a state of wonderment at the magnitude of the enterprise and the almost miraculous success of it.”

The painting toured internationally, including a trip to London, where it drew further acclaim.

Where Is The Heart of the Andes Located Today?

Today, The Heart of the Andes resides in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, where it continues to awe visitors. It remains one of the museum’s crown jewels, displayed prominently and accompanied by educational materials to help viewers appreciate its full complexity.

Why The Heart of the Andes Still Matters

In an era of rapid industrialization, climate change, and cultural fragmentation, The Heart of the Andes serves as a poignant reminder of the beauty and fragility of the natural world. It invites us to see nature not merely as a resource, but as a living, breathing entity imbued with spiritual significance.

Church’s vision of interconnectedness, between man and nature, science and spirituality, art and observation, is more relevant than ever. The painting bridges divides: between continents, disciplines, and belief systems.

It’s not just a landscape. It’s a worldview.

Frederic Edwin Church’s The Heart of the Andes is more than a technical marvel, it is a philosophical and spiritual landmark in American art. By blending scientific accuracy with romantic sublimity, Church created a painting that transcends time and geography.

It is a window into the divine complexity of the Earth, a celebration of creation, and a call to reverence. Whether viewed through the lens of theology, ecology, or aesthetics, The Heart of the Andes stands as a masterpiece of vision, execution, and meaning.

In gazing upon it, we are not merely observers, we are participants in the vast, interconnected story of life itself.