Merry Company by Gerrit van Honthorst

A Journey into Dutch Golden Age Revelry, Symbolism, and Social Commentary

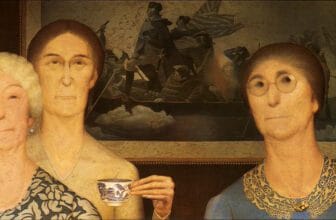

In the dim candlelit rooms of the Dutch Golden Age, where music mingled with laughter and shadow played with light, Gerrit van Honthorst’s “Merry Company” comes alive, not just as a vibrant genre painting, but as a profound window into 17th-century life, morality, and the enduring tension between pleasure and propriety. Painted during a pivotal era in Dutch history, “Merry Company” is not merely a festive snapshot of a jovial gathering; it is a layered composition brimming with meaning, social commentary, and masterful technique.

Who Was Gerrit van Honthorst?

Before analyzing the painting itself, it is essential to understand the artist behind it. Gerrit van Honthorst (1592–1656) was a Dutch painter born in Utrecht, one of the key cities in the Dutch Republic. Trained under Abraham Bloemaert, Honthorst later traveled to Italy, where he absorbed the dramatic lighting and theatrical realism of Caravaggio, becoming one of the most prominent Caravaggisti, northern European followers of Caravaggio.

Upon returning to the Netherlands, Honthorst translated this Italianate tenebrism into his own cultural context, becoming renowned for his candlelit scenes and genre paintings. His work bridges the religious and the secular, the sacred and the profane, through vivid depictions of musicians, revelers, and fortune-tellers. Among these, “Merry Company” stands out as a quintessential expression of his style and philosophical undertones.

What Is the Merry Company Painting All About?

The term “Merry Company” refers to a genre in 17th-century Dutch painting that portrays groups of people enjoying music, drink, and conversation, often in taverns or private interiors. Honthorst’s “Merry Company” (circa 1620s) perfectly encapsulates this tradition, while pushing its narrative and symbolism deeper than many of his contemporaries.

In the painting, we see a group of elegantly dressed men and women gathered around a table. A lute player, likely a hired musician or perhaps part of the reveling group, serenades the group. Glasses of wine, rich fabrics, and playful expressions animate the scene. A single candle, the hallmark of Honthorst’s work, illuminates the scene with dramatic chiaroscuro, casting flickering shadows across the figures’ faces and emphasizing their features and emotional expressions.

At first glance, the scene might appear to be a simple celebration, frivolous, warm, perhaps a portrait of prosperity. But Honthorst’s genius lies in how he challenges the viewer to look beyond the surface.

What Is Happening in the Painting?

The painting captures a moment of lively festivity. The characters are absorbed in music, flirtation, and drink. One woman looks directly at the viewer, almost with an inviting or challenging gaze. Another figure gestures toward the musician or perhaps the wine, suggesting conversation or even seduction.

But look closer, and you begin to notice subtle disruptions in this otherwise cheerful harmony. A man, perhaps drunk, leans too closely. The candlelight flickers on a face turned away, lost in contemplation or weariness. A dog or a bird, sometimes present in other versions of this genre, might lurk in the background as a symbol of loyalty, or base instincts.

This juxtaposition of lively appearance and underlying disorder is essential to the painting’s message. The scene teeters between pleasure and consequence, social grace and impropriety.

Symbolism and Meaning in Merry Company Painting

Honthorst’s “Merry Company” is dense with symbolic motifs, many of which would have been instantly recognizable to a 17th-century viewer:

1. The Candlelight

Light in this painting is not merely functional; it is symbolic. The candle, central in the composition, symbolizes life, time, and the transience of earthly pleasures. The flickering flame, casting light but also emphasizing darkness, is a metaphor for how quickly moments of joy can vanish, how ephemeral the pleasures of the flesh are.

2. Musical Instruments

The lute and other instruments are long-standing symbols of love, harmony, and seduction. But in Dutch moralizing traditions, they can also imply lust and moral decay. In the “Merry Company,” music acts as both a connector and a distractor, drawing people together while possibly leading them into vice.

3. Wine and Glassware

Wine is synonymous with celebration, but excessive drinking was also a moral concern in Calvinist Dutch society. The glasses raised high, the red wine flowing freely, these may represent more than just enjoyment. They hint at hedonism and the dangers of indulgence.

4. Fashion and Gesture

The clothing is opulent, luxurious, again, a status symbol but also a cue to potential vanity. Some gestures, like a suggestive lean or a sidelong glance, border on flirtation, hinting at the theme of fleeting romantic or sexual encounters.

Together, these elements form an allegorical painting, a visual story not only about joy, but about the choices that accompany freedom, prosperity, and time.

What Type of Art Is Merry Company?

“Merry Company” is best classified as a genre painting, a category that depicts scenes from everyday life. Unlike historical or religious painting, genre art was more accessible and secular, often consumed by the rising Dutch middle class.

But Honthorst’s execution is particularly notable for its:

Caravaggesque Chiaroscuro: Inspired by Caravaggio, Honthorst utilizes stark contrasts between light and shadow to give the painting a theatrical quality.

Realism: The details, textiles, facial expressions, posture, are rendered with an almost photographic realism, which was revolutionary at the time.

Narrative Composition: Rather than a static group portrait, “Merry Company” tells a story. Every figure plays a role, contributing to the emotional and symbolic interplay.

This painting also shares kinship with vanitas painting, which subtly reminds viewers of the brevity of life and the vanity of earthly pursuits. While less explicit than a skull or extinguished candle, the symbolic layering of “Merry Company” aligns it with this contemplative genre.

Who Are the Figures in the Painting?

Though they are not named, the figures in Honthorst’s “Merry Company” serve as archetypes rather than individuals:

The musician represents art and entertainment, but also the seductiveness of art.

The young woman staring at the viewer is both subject and provocateur, possibly a courtesan or hostess, suggesting allure and risk.

The older man, often present in similar paintings, might represent a patron or a voyeur, a symbol of the societal power dynamics at play.

The onlookers form a chorus of expressions, from joy to mischief to contemplation, reflecting a full emotional spectrum and inviting the viewer to decide where they stand.

How Was It Painted? The Technique Behind the Work

Gerrit van Honthorst’s technical approach was deeply influenced by his time in Rome. He adopted:

Oil on canvas as his primary medium.

Layered glazing techniques to create luminous skin tones and realistic fabric.

Controlled brushwork that allowed him to articulate fine details like lace, hair, and reflections.

Single-source lighting (usually a candle or torch), creating an internal spotlight that directed the viewer’s gaze and gave the scene its dramatic intensity.

He likely sketched studies from live models to capture authentic gestures and expressions. Honthorst’s command of group dynamics and light psychology is perhaps his most defining trait.

The Broader Context: Society and Morality in the Dutch Golden Age

The Dutch Republic in the 17th century was prosperous, cosmopolitan, and deeply influenced by both Calvinist ethics and mercantile ambitions. Paintings such as “Merry Company” served not only as decoration but as moral dialogues for the home.

Buyers of such art were often merchants or urban elites who enjoyed the prosperity of the time but were also acutely aware of the need for virtue and self-discipline. Art offered a safe space to explore these tensions, between joy and guilt, indulgence and restraint.

Honthorst, though Catholic, worked successfully within this Protestant milieu by crafting scenes that could be read in multiple ways: as celebrations of life or subtle warnings about excess.

Where Is the Merry Company Painting Today?

Multiple versions and interpretations of “Merry Company” exist, as Honthorst painted several similar scenes throughout his career. The most famous and widely studied version is currently housed in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, one of the world’s leading repositories of Dutch Golden Age art.

Other versions and similar works by Honthorst can be found in:

The Mauritshuis in The Hague

The National Gallery in London

The Uffizi Gallery in Florence

Various private collections and European museums

Each version contains unique compositional elements but maintains the same core themes, celebration laced with caution.

Why Merry Company Still Matters

Nearly 400 years after its creation, Gerrit van Honthorst’s “Merry Company” continues to resonate not just for its beauty, but for its depth. It reminds us that art, even when depicting joy, is rarely simple. Through light and shadow, pleasure and prudence, Honthorst invites us to reflect on the complex dance of life, its temptations, its delights, and its consequences.

“Merry Company” is both a celebration and a cautionary tale, a work of realism and allegory. As viewers, we are not just invited to observe, we are asked to participate, to question, and perhaps to locate ourselves within the scene. Are we revelers? Are we voyeurs? Are we judging or indulging?

This ambiguity, masterfully rendered through paint, is what elevates Honthorst’s “Merry Company” from a simple genre painting to a timeless reflection on human nature.