The Life, Art, and Legacy of Catharina van Hemessen

In the vibrant and dynamic world of Renaissance art, dominated by towering male figures such as Michelangelo, Titian, and Holbein, one name stands out as a pioneering woman who carved a place for herself in an era when women were rarely permitted to hold the brush professionally: Catharina van Hemessen (1528 – after 1565).

A Flemish Renaissance painter, Catharina is today remembered not only for her artistry but also for her historical significance. She is often hailed as the first known female painter to have created a self-portrait, an achievement that changed the trajectory of how women were seen in the visual arts. Although fewer than two dozen works of hers survive, they represent an extraordinary legacy , both as precious examples of Renaissance portraiture and as milestones in the history of women artists.

This article will explore Catharina’s story, her most famous paintings, the historical context of her life, the number and locations of her surviving works, and her enduring legacy in art history.

The Story of Catharina van Hemessen

Catharina van Hemessen was born in Antwerp in 1528, during the height of the Northern Renaissance. She was the daughter of Jan Sanders van Hemessen, a renowned painter in his own right, known for his religious works and contributions to the development of genre painting. Growing up in her father’s workshop, Catharina was immersed in the world of pigments, panels, and patrons from an early age.

Unlike many women of her time, Catharina was fortunate to receive an artistic education from her father, who recognized her talent. Antwerp, then part of the Habsburg Netherlands, was a thriving artistic hub where painters enjoyed patronage from the wealthy merchant class and the Church. However, despite the flourishing art scene, women had little to no opportunities to enter guilds or sell their works independently. Catharina defied these societal limitations.

In 1548, at the age of about 20, she painted her groundbreaking self-portrait at the easel, which is widely considered to be the first known self-portrait of an artist (male or female) seated at the easel and actively engaged in painting. In doing so, Catharina boldly declared her identity not merely as a woman but as a professional artist , an extraordinary act in an era that often relegated women to anonymity.

She later gained the patronage of Mary of Austria, sister of Emperor Charles V and regent of the Netherlands. In 1556, when Mary moved to Spain, Catharina followed her as a court painter, further cementing her reputation. After Mary’s death in 1558, Catharina returned to Antwerp. She married Christian de Morien, an organist, and seems to have retired from painting not long after , a common fate for many women artists whose careers were often cut short by marriage.

What Catharina van Hemessen Is Known For

Catharina van Hemessen is primarily known for:

Her self-portraiture – She was the first artist, male or female, known to depict herself at work, giving us a window into the life of an artist in the Renaissance.

Her portraits of women and men – Her surviving works are mostly small-scale portraits of well-to-do citizens of Antwerp, painted with precision, restraint, and sensitivity. Unlike the grandiose portraits of kings and noblemen created by her male contemporaries, Catharina’s works often focused on middle-class patrons and emphasized realism, subtle emotion, and detail.

Her pioneering role for women in art – While not prolific compared to her male peers, Catharina stands out for her role in breaking barriers. She proved that women could be recognized as professional artists and set the stage for later women painters such as Sofonisba Anguissola, Artemisia Gentileschi, and Judith Leyster.

Catharina van Hemessen’s Most Famous Paintings

Although only about 20 works are securely attributed to her, several stand out as her most significant contributions to Renaissance art.

1. Self-Portrait at the Easel (1548)

Her most famous and iconic work, this small painting (32 x 25 cm, now in the Kunstmuseum, Basel) shows the young Catharina at work. She sits before an easel, brush in hand, paused mid-stroke as though acknowledging the viewer. With calm dignity, she presents herself not merely as a woman but as a creator , a radical statement for her time. This work is often celebrated as one of the most important self-portraits in Western art history.

2. Portrait of a Woman (1551, Antwerp Royal Museum of Fine Arts)

This portrait depicts a wealthy Antwerp woman in fine attire, painted with meticulous attention to detail in the textures of fabric and jewelry. The sitter’s solemn expression and reserved demeanor reflect the Flemish taste for restraint, yet Catharina imbues her subject with quiet dignity.

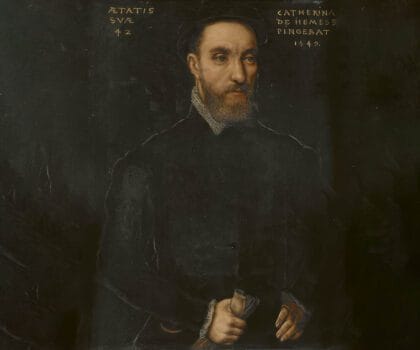

3. Portrait of a Man (c. 1550)

Held in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, this work exemplifies Catharina’s skill in male portraiture. The sitter is rendered with psychological depth, highlighting her ability to go beyond mere likeness to suggest the sitter’s character.

4. Portrait of a Young Woman Playing the Virginals (c. 1548)

Attributed to her with some debate, this painting links music and art, showcasing a young woman at a keyboard instrument. It may reflect Catharina’s connection to courtly life, where music and painting often intersected as symbols of refinement.

How Many Paintings Does Catharina van Hemessen Have?

Today, around 20 paintings are attributed to Catharina van Hemessen, though some attributions remain debated among scholars. Most are small-scale portraits, painted in oil on panel, typically featuring bust-length depictions of sitters against dark backgrounds. Her oeuvre is modest compared to her male counterparts, partly due to the societal limitations placed upon women artists of her era and her early retirement from painting after marriage.

The Most Expensive Painting of Catharina van Hemessen

Unlike the works of more famous Renaissance painters, Catharina’s paintings rarely come to market, making it difficult to establish a definitive record of her highest-selling work. Her Self-Portrait at the Easel is held in a museum and therefore considered priceless and not for sale.

When her works do appear at auction, they attract significant interest due to their rarity and historical importance. Some of her portraits have been sold for six-figure sums, though none have reached the multi-million-dollar records set by her male contemporaries. Still, her self-portrait and key portraits are considered invaluable cultural treasures.

Locations of Catharina van Hemessen’s Paintings

Catharina’s surviving works are scattered across major European collections, where they are treasured as rare examples of female-authored Renaissance art. Notable locations include:

Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland – Self-Portrait at the Easel (1548)

Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, Belgium – Several portraits, including Portrait of a Woman (1551)

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria – Portrait of a Man and other works

National Gallery, London – Houses a small portrait attributed to her

Other private and smaller European collections – Several of her portraits remain in less-publicized holdings.

Catharina van Hemessen’s Legacy

Catharina’s significance transcends the number of works she created. Her legacy can be understood in several ways:

Pioneering Female Representation – She was the first artist known to paint herself at work, declaring her identity as both a woman and an artist. This act made her a role model for future generations of women artists.

Contribution to Northern Renaissance Portraiture – Though fewer in number, her portraits stand alongside the works of contemporaries in terms of technical skill and psychological depth.

Inspiration for Later Women Artists – Artists such as Sofonisba Anguissola (Italy), Lavinia Fontana (Italy), and later Artemisia Gentileschi (Italy) built upon the path Catharina helped open, proving that women could claim a space in the professional art world.

Cultural and Historical Symbol – Today, her name is invoked not just in art historical discussions but also in feminist discourse, as an emblem of perseverance and talent in the face of systemic barriers.

Catharina van Hemessen may not have produced as many works as her male peers, nor commanded the astronomical sums their paintings fetch at auction. But the value of her contribution to art history cannot be measured in numbers or prices alone.

Her self-portrait at the easel remains one of the most groundbreaking and courageous works of the Renaissance , a quiet yet revolutionary assertion of identity, talent, and presence. Her portraits, though modest in scale, radiate the dignity and humanity of her sitters. And her career, though brief, stands as a testament to the power of talent and determination to overcome societal boundaries.

Catharina van Hemessen’s story is not just about paintings; it is about a woman who dared to paint herself into history, ensuring that her voice , and the voices of countless women who followed , would never again be silent in the halls of art.