Meaning of Dancers at the Barre Painting by Edgar Degas

Edgar Degas, one of the most prominent French painters of the 19th century, is celebrated for his innovative portrayal of movement, particularly in the world of ballet. Among his many iconic works, Dancers at the Barre stands as a profound representation of his artistic vision, thematic focus, and deep interest in the human figure in motion. This painting is more than just a depiction of ballerinas at practice, it’s a masterclass in composition, symbolism, and psychological depth.

This article delves into the intricate details of Dancers at the Barre, including how it was created, the story behind it, its stylistic identity, symbolic undertones, and where it resides today. By the end, you’ll gain a deeper appreciation for the complexity and genius behind this seemingly simple yet emotionally layered painting.

A Brief Introduction to Edgar Degas

Before examining the painting itself, it’s crucial to understand the man behind the masterpiece. Edgar Degas (1834–1917) was a French artist widely associated with the Impressionist movement, although he preferred to call himself a “Realist” or “Independent.” He is best known for his depictions of dancers, women at their toilette, racehorses, and scenes of modern urban life. Degas was not as interested in painting nature or landscapes, like many of his Impressionist peers, but rather in capturing human figures in candid, often unguarded moments.

His work straddles both classical technique and modern subject matter. Trained in traditional academic painting, Degas applied those rigorous skills to scenes of contemporary Paris, combining realism, psychological complexity, and a unique observational style. His fascination with ballet and ballerinas wasn’t merely aesthetic, it was also social and psychological. Ballet dancers, often from working-class backgrounds, provided a rich canvas for exploring themes of discipline, femininity, social mobility, and voyeurism.

Creation of Dancers at the Barre

Dancers at the Barre was painted by Edgar Degas between early 1900 and 1905, toward the later part of his career. By this time, Degas was struggling with deteriorating eyesight, which forced him to rely more heavily on memory, sketches, and experimentation. Despite this limitation, or perhaps because of it, his work during this period became more expressive and bold.

The painting is an oil on canvas, measuring approximately 51 1/4 x 38 1/4 inches (130.2 x 97.2 cm). It was not a commissioned work but rather part of Degas’s long-standing obsession with dancers, which had captivated him for over four decades. He produced hundreds of works in various media (pastels, drawings, sculpture, and oils) centered around ballet, rehearsals, backstage views, and dressing rooms.

Degas did not paint Dancers at the Barre in a single sitting or even within a short period. Like many of his paintings, it underwent multiple revisions. He was known for reworking his compositions extensively, sometimes over many years. In fact, X-ray analysis of Dancers at the Barre has revealed underlying sketches and earlier versions, suggesting that the final composition was the result of significant evolution.

What Is Happening in the Painting?

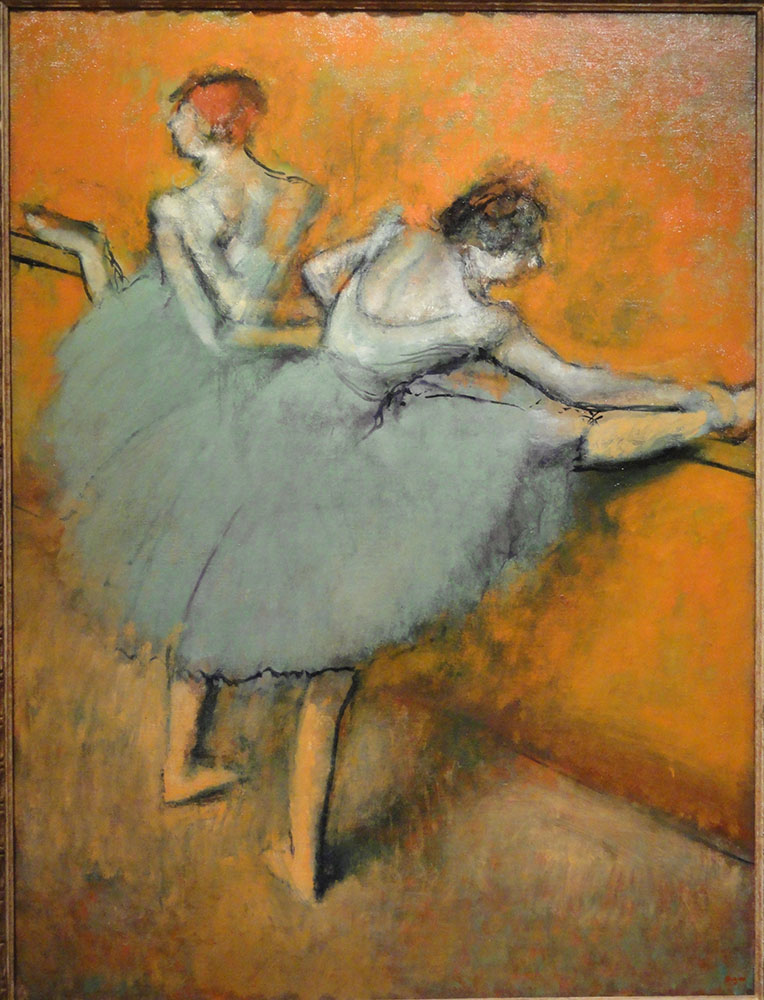

At first glance, Dancers at the Barre appears deceptively simple. It shows two ballerinas in rehearsal attire, stretching with one leg on the barre, a familiar pose to anyone acquainted with dance. Their backs are turned to the viewer, emphasizing the curve of their spines and the flex of their legs. The environment is sparse, with muted colors and minimal background details, allowing full focus on the figures.

However, a closer inspection reveals the complexity beneath the surface. The ballerinas are not performing for an audience; they are caught in a moment of discipline and repetition, emblematic of the daily grind that defines a dancer’s life. Their identical posture suggests a studied routine, while their mirrored positioning introduces a subtle rhythm into the composition. There is no glamour, no stage lights, just effort, dedication, and the quiet intensity of preparation.

This is a behind-the-scenes glimpse into the world of ballet, revealing the physical strain and mental focus required of dancers. Degas strips away the theatrical illusion to reveal the labor that underpins it. In doing so, he humanizes his subjects and elevates the everyday reality of artistic discipline into something profound.

What Type of Art Is Dancers at the Barre?

Dancers at the Barre is typically classified as Impressionist, though it also embodies characteristics of Realism and Post-Impressionism. Degas was a founding member of the Impressionist group, but he often distanced himself from the label. Unlike many of his peers, he rarely painted outdoors and preferred the controlled interior environments of studios and rehearsal rooms.

Stylistically, the painting features hallmark Impressionist traits such as:

Loose brushwork

Emphasis on light and shadow

Everyday subject matter

Focus on movement and the human figure

Yet, Degas’s method was more structured than most Impressionists. He conducted meticulous studies, used photographic references, and layered his compositions over time. His work reveals a fascination with form, anatomy, and the geometry of space, attributes more aligned with classical traditions.

In this particular painting, the vertical lines of the barre and floor intersect with the curved forms of the dancers’ bodies, creating a visual harmony that balances movement and stillness. The subdued color palette, composed largely of earth tones and soft pastels, contributes to the contemplative mood.

Symbolism and Meaning

Dancers at the Barre is a study in discipline, repetition, and physical endurance. Degas shows the uncelebrated reality of dance, a profession often associated with beauty and grace but built on intense, almost punishing rigor.

There is symbolic richness in the choice of pose. The act of stretching at the barre represents preparation, transition, and discipline, core values not just in dance but in any pursuit of excellence. It evokes the idea that mastery is not achieved in the spotlight but in the unglamorous moments of routine and perseverance.

Some art historians also interpret the mirrored dancers as metaphors for duality, perhaps reflecting different aspects of the self, or the tension between artifice and authenticity. The anonymous presentation of the ballerinas, with their backs turned to the viewer, adds an element of mystery and universality. They are not individual portraits but archetypes of the working artist.

Additionally, Degas’s perspective, observing from behind, as if unseen, can be read through the lens of voyeurism. The viewer becomes a silent observer of a private moment, raising questions about the gaze and the objectification of the female form. Yet unlike more romanticized portrayals, Degas’s dancers are dignified and strong, not decorative. They own their space, commanding attention through effort, not ornamentation.

The Role of Space and Composition

One of the most striking aspects of Dancers at the Barre is its use of space. Degas masterfully manipulates depth, form, and line to create a composition that is at once intimate and expansive. The background is intentionally non-descriptive, forcing the viewer’s focus onto the dancers themselves. The vertical barre acts as an anchor, dividing the space and emphasizing the dancers’ symmetry.

The floor, rendered in muted tones, extends outward, giving a sense of openness while maintaining a controlled, almost clinical atmosphere. This plays into Degas’s broader interest in architecture and interior space, his ballet rooms are often filled with unseen lines and grids that structure the chaos of motion.

The cropping of the figures is also notable. Degas was influenced by Japanese woodblock prints and photography, both of which employed unusual framing techniques. By cutting off parts of the dancers’ limbs or placing them at the edge of the canvas, he creates a sense of immediacy and spontaneity, as if the viewer has stumbled upon this moment in real-time.

Degas’s Process and Medium

Degas was known for experimenting with different media, often combining oil, pastel, and charcoal in innovative ways. In Dancers at the Barre, he used oil on canvas, but close inspection reveals a layered technique that includes underpainting, scumbling, and glazing.

He began with numerous sketches and studies, some drawn from live models, others from memory. His preparatory work was exhaustive; he would often draw the same pose dozens of times until he felt he had captured its essence. These drawings then served as the foundation for his paintings, which were often reworked multiple times. In fact, some scholars argue that the process of creation was as important to Degas as the final product.

His brushwork in this painting is deliberate yet fluid. The dancers’ limbs are outlined with soft, feathery strokes that convey movement, while their torsos are more solid and defined, grounding them in space. The contrast between motion and stillness is central to the painting’s emotional impact.

Where Is Dancers at the Barre Painting Located Today?

Today, Dancers at the Barre is housed in The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., one of the most prestigious museums of modern art in the United States. The painting was acquired by Duncan Phillips, the museum’s founder and an early advocate of modernist art. It remains one of the highlights of the collection, admired by both scholars and the public for its elegance, complexity, and emotional depth.

Visitors to the museum can view the painting in person, where its texture, scale, and brushwork can be appreciated in full. Seeing it up close offers a vastly different experience than viewing reproductions, the nuances of light, color, and line come alive, revealing the full extent of Degas’s technical brilliance.

A Dance of Meaning and Form

Dancers at the Barre is far more than a portrait of two ballet students. It is a window into Edgar Degas’s mind, his obsessive attention to detail, his empathy for working women, his fascination with motion, and his commitment to depicting truth over theatricality. The painting’s symbolic layers, discipline, repetition, duality, and labor, invite viewers to consider not only the dancers’ lives but also the sacrifices inherent in any artistic endeavor.

In presenting a quiet moment of preparation rather than performance, Degas subverts our expectations and challenges us to find beauty in restraint, poetry in the mundane, and elegance in effort. The result is a timeless work of art that continues to captivate, provoke, and inspire. image/wikimedia