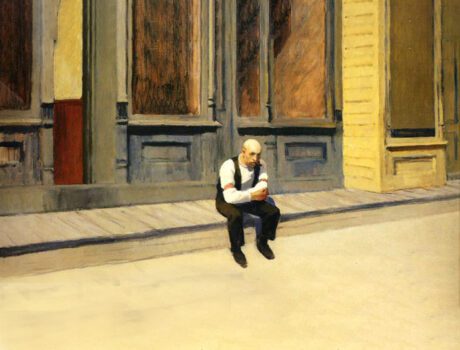

The Meaning of Edward Hopper’s “Sunday” Painting (1926)

Edward Hopper’s 1926 painting Sunday is a visual meditations on solitude, modernity, and the psychological undercurrents of American life in the early 20th century. With its stark composition, minimal color palette, and a lone figure bathed in harsh sunlight, Sunday encapsulates many of the themes that define Hopper’s oeuvre. The painting is not merely a quiet urban scene; it is a subtle yet powerful narrative about isolation, the human condition, and the passage of time. This story post delves into the creation, meaning, symbolism, and enduring impact of Sunday, exploring how Hopper transformed an ordinary moment into a haunting tableau of emotional resonance.

Who Painted Sunday (1926) and How It Was Created

Edward Hopper, an American realist painter and printmaker, was born in 1882 in Nyack, New York. Trained initially as an illustrator, Hopper studied at the New York School of Art under Robert Henri, who encouraged a realist approach and championed painting modern life. Hopper, however, developed a distinctive style characterized by sharp lines, architectural clarity, subdued colors, and a strong sense of narrative ambiguity.

By the 1920s, Hopper had found his voice as an artist, frequently depicting urban and rural American settings imbued with psychological tension and silence. His works reflected the alienation and introspection of the modern era. It was in this context, in 1926, that he painted Sunday.

Sunday was created during a period of creative consolidation for Hopper. He had begun to receive more recognition and financial success, enabling him to focus more fully on painting. Using oil on canvas, Hopper employed a tight compositional technique. The painting’s geometry is meticulously constructed, emphasizing flatness and depth simultaneously. Hopper often sketched extensively and took photographs to plan his paintings. It is likely that he synthesized various elements from observed reality rather than capturing a literal scene, merging memory, imagination, and lived experience into one stark image.

What the Sunday (1926) Painting Is All About

At first glance, Sunday appears deceptively simple: a solitary man sits on a low curb in front of a row of commercial buildings, bathed in hard, almost oppressive sunlight. The streets are empty. There is no obvious activity, no movement, and no clear narrative. Yet, beneath this silence lies a wealth of psychological and symbolic meaning.

The scene evokes a sense of suspended time. It is Sunday, traditionally a day of rest, reflection, and spiritual observance. But the absence of churchgoers, community gatherings, or domestic warmth renders this Sunday cold and introspective. Hopper’s subject is not merely enjoying a moment of peace; he is enveloped in a deep, almost existential quietude.

Hopper often used urban landscapes to explore inner emotional states, and Sunday is a prime example. The buildings are impersonal, the streets are barren, and the lighting is harsh rather than inviting. The man, possibly a shop worker or a resident, seems frozen in thought, his purpose unclear, his expression unreadable. He is at once central and marginal, physically prominent in the composition but emotionally distant from the viewer.

This ambiguity is central to Hopper’s work. He does not dictate what the painting is about; instead, he opens up a space for contemplation. Sunday becomes a canvas not just for paint, but for projection, viewers bring their own experiences, emotions, and interpretations to the scene, filling in the blanks that Hopper deliberately leaves.

Symbolism and Deeper Meaning of Sunday

1. The Stillness of Time:

The title Sunday sets a temporal context. In American culture, Sunday is associated with rest, religion, family, and tradition. However, the painting subverts these associations. Instead of warmth and communion, Hopper presents solitude and vacancy. This subversion suggests a breakdown or transformation of traditional values in modern life. The man’s inactivity becomes symbolic of spiritual or existential pause, perhaps even stagnation.

2. Alienation and Modernity:

The urban environment in Sunday is pristine yet impersonal. The rise of industrialization and urbanization in early 20th-century America created spaces that were efficient but isolating. Hopper captures this psychological impact, cities full of people yet full of loneliness. The single figure becomes a symbol of modern alienation, someone surrounded by civilization yet untouched by its connections.

3. The Human Condition:

The man in the painting is not heroic or glamorous; he is ordinary, perhaps even invisible in a societal sense. This ordinariness is crucial, Hopper elevates the everyday experience into a subject worthy of artistic and philosophical exploration. The man’s introspection and stillness reflect a universal human condition: the search for meaning, the burden of time, and the complexity of self-awareness.

4. Light and Shadow as Emotional Tools:

Hopper uses light not just for realism, but for mood. The hard shadows and bright highlights serve to isolate elements within the painting, particularly the man, who is simultaneously illuminated and trapped by the light. The contrast between light and dark becomes a metaphor for emotional contrasts, hope versus despair, clarity versus ambiguity, presence versus absence.

5. Architecture and Space as Psychological Constructs:

The buildings in Sunday do not merely create a setting, they serve as psychological walls. Their blocky structure and repetitive patterns suggest monotony, routine, and even confinement. The empty street becomes a corridor of silence, where the mind turns inward and time stretches indefinitely.

What Is Happening in the Painting?

There is no action in the traditional narrative sense. The man is seated, perhaps waiting, perhaps resting. His posture is relaxed yet heavy. His attire suggests he is working-class, possibly someone who works in or lives above one of the storefronts. The fact that the shops are closed reinforces the day’s quietness.

What is happening is a psychological moment rather than a physical one. It is a pause, a breathing space filled with silence, introspection, and ambiguity. The man might be reflecting on his life, enduring loneliness, or simply enjoying a rare moment of peace. This ambiguity is intentional and crucial. Hopper resists sentimentality and clear storytelling, allowing the painting to resonate in multiple, often contradictory, emotional registers.

What Type of Art Is Sunday?

Sunday is a quintessential example of American Realism, a movement that sought to depict everyday subjects in a truthful, unidealized manner. Yet, Hopper’s realism is not documentary or literal, it is psychological, symbolic, and stylized. His work is often described as Modern Realism or Psychological Realism because of its emphasis on mood, solitude, and emotional undercurrents.

Some critics also link Hopper to the Ashcan School, given his early influences, but Hopper’s style is cleaner, more structured, and less gritty than that of Ashcan artists. Unlike the busy street scenes favored by that school, Hopper’s paintings are about quiet moments and internal landscapes.

Stylistically, Sunday also exhibits qualities of Minimalism and Symbolism. The reduction of detail and deliberate use of empty space create a meditative visual field. The painting communicates not through action or complexity but through absence, stillness, and suggestion.

Where Is Sunday (1926) Painting Located Today?

As of this writing, Sunday is housed in the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City. The Whitney holds the largest repository of Hopper’s work, thanks in part to the generosity of his widow, Josephine Nivison Hopper, who bequeathed much of his estate to the museum upon her death in 1968. Sunday is part of the museum’s permanent collection and is periodically displayed in rotation with other works by Hopper and contemporaneous American artists.

Visitors to the Whitney can experience Sunday in the context of Hopper’s broader body of work, which includes iconic paintings such as Nighthawks (1942), Automat (1927), and Early Sunday Morning (1930). Together, these works form a powerful narrative about the American experience in the first half of the 20th century.

Nearly a century after its creation, Sunday continues to resonate deeply with modern audiences. In an age defined by digital connectivity and constant motion, the painting’s stillness and introspection offer a counterpoint, a visual invitation to slow down, reflect, and confront the emotions that lie beneath the surface of daily life.

During global events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, Hopper’s work, especially Sunday, experienced a resurgence in relevance. The empty streets, isolated figures, and quiet urban landscapes mirrored the lived experiences of millions in lockdown. Sunday became not just a historical artifact, but a contemporary mirror.

Moreover, the painting invites ongoing conversations about mental health, loneliness, and the impact of urban design on emotional well-being. In an increasingly urbanized and digitized world, Hopper’s exploration of physical proximity and emotional distance remains as urgent and thought-provoking as ever.

The Enduring Power of Sunday (1926)

Edward Hopper’s Sunday is a masterclass in visual storytelling through minimalism. By stripping away distractions and focusing on a single man, a single moment, and a single day, Hopper creates a space where viewers confront profound emotional and existential questions. It is a painting about stillness, but not stasis; about loneliness, but not despair; about emptiness, but not absence.

The painting continues to captivate not because it offers answers, but because it articulates questions, about time, self, society, and the spaces we inhabit. In doing so, Sunday stands as one of Hopper’s most enduring works, a quiet but powerful testament to the inner life of modern man.

Whether seen as a commentary on modernity, a portrait of working-class America, or a meditation on the soul’s quiet moments, Sunday remains a vital piece of American art, one that invites every viewer to pause, sit in the silence, and listen to the stories that arise when the world stops moving.