Italian Renaissance vs. Northern Renaissance Paintings

A Collector’s Story-Guide to Two Worlds of Genius

The Two Suns That Lit the Dawn of European Art

To understand the Renaissance, a collector must imagine Europe not as a unified cultural field but as an enormous continent of distinct visions, two radiant suns rising at opposite ends of the sky. One sun rose over the warm valleys of Tuscany and the city-states of central Italy, illuminating marble piazzas with new philosophies, classical ideals, and revived humanism. The other emerged over the mist-laden cities of the Low Countries, glowing through the windows of merchant houses in Bruges, Ghent, and later Antwerp, revealing a world built not on classical revival but on the intimacy of domestic interiors, the emotional resonance of everyday objects, and the astonishing new precision of oil painting.

Collectors today often speak about the Renaissance as if it were a single stylistic explosion, but it was in truth an intricate duet. Italy created the architecture of rebirth: perspective, anatomy, monumental composition, and reverence for Greco-Roman forms. The Northern world created the mirror: a meticulous, almost divine attention to surface, texture, reflection, symbolism, and the minute particulars of lived experience. Owning work from either sphere does not simply mean possessing a painting; it means holding a complete worldview in your hands.

Understanding this duality is essential for anyone considering building a collection, because the cultural currents that produced each school, its materials, patrons, spiritual expectations, and technical breakthroughs, continue to shape market values and the rarity of surviving pieces.

Classical Bones, Humanist Minds, and Theatrical Light

In the fifteenth century, Italy was the crossroads of rediscovery. Ancient manuscripts resurfaced in monasteries. Sculptures were lifted from buried Roman ruins. Wealthy families such as the Medici financed the study of antiquity not as nostalgia but as a living, breathing blueprint for the future. A new belief arose: that the human body was a vessel of proportion and divinity, worthy of precise study and heroic depiction.

Italian Renaissance painters pursued this idea with enormous intellectual energy. They dissected bodies to understand the architecture of muscle and bone. They studied geometry to construct coherent spatial environments where figures could inhabit a believable world. They immersed themselves in the writings of Plato and Aristotle to understand virtue, rationality, and the nature of beauty. Their paintings became visual treatises, compositions meant not merely to delight but to elevate the mind.

Collectors quickly recognize these Italian traits: sculptural figures, symmetrical compositions, balanced proportions, and a sense of theatrical architecture that suggests a stage set for mythological or religious drama. Even in small devotional panels from Florence or Siena, the Italian emphasis on idealization radiates from the picture plane. The Madonna is serene, the saints monumental, the drapery described with rhythms that echo the folds of classical marble.

Where Italian painters excelled was creating an intellectual order, the sense that every figure is part of a perfectly arranged universe. This is why Italian Renaissance art remains so central to museums and private collections: it became the foundation of Western artistic training for centuries.

Mirrors, Mysteries, and the Soul of Everyday Life

While Italy looked backward to antiquity for its rebirth, the North looked inward. Northern European cities were thriving commercial hubs driven by trade, textiles, and mercantile wealth. Their patrons were not always aristocrats or princes but wealthy merchants and urban professionals who wanted images of the world they recognized: domestic interiors filled with polished brass vessels, delicate fabrics, prayer books, animals, gardens, and the palpable textures of life.

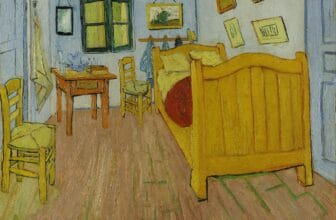

The Northern Renaissance did not develop from the rediscovery of ancient philosophy; it emerged from technical innovation, most importantly, the refinement of oil painting. Jan van Eyck and his contemporaries elevated oil to a new luminosity, allowing for glazing techniques that produced unfathomably realistic surfaces. The North became a laboratory of light. Artists learned to depict the transparency of glass, the reflection of a windowpane on a polished floor tile, or the subtle sheen of fur and velvet with microscopic accuracy.

Collectors drawn to Northern works often feel they are entering a world where material reality becomes a spiritual revelation. Northern artists concealed narratives within objects: a dog signifying fidelity, flowers symbolizing purity or mortality, a discarded shoe expressing sanctity or marriage. The smallest item could carry profound meaning, and the viewer was invited into a contemplative experience that rewarded prolonged attention.

If Italian Renaissance art is a declaration, Northern Renaissance art is a whispered conversation.

Comparing the Two Renaissances: Flesh and Stone vs. Light and Life

For collectors, one of the most compelling aspects of Renaissance art is understanding how two cultures arrived at such distinct visual languages while sharing the same epoch. When a collector places an Italian panel next to a Northern one, the contrast is immediate, almost theatrical.

Italian paintings feel carved. Figures appear as if sculpted from marble, even when they are rendered in tempera or oil. The compositions tend toward clarity and harmony; one senses the echo of classical architecture in the structural order of every element. The focus is on the ideal, a perfected human form, a pristine heroic narrative, a world polished to intellectual clarity.

Northern paintings, by contrast, feel breathed into existence. The textures are astonishingly tactile, from woven threads to pearls and metalwork. Light is not merely illumination but a psychological force that shapes mood, symbolism, and the emotional tenor of each scene. Instead of ideal bodies, Northern artists concentrated on individuality. Faces reveal age, character, worry, and humanity in ways Italian painters rarely attempted until much later.

These differences continue to affect collecting today. Italian works, even small devotional panels, often command high prices because they embody the birth of Western classicism. Northern works, many of which survive in strong condition due to the durability of oil paint, attract collectors who value detail, subtlety, and the poetic resonance of domestic life.

Monumental Theology vs. Intimate Devotion

Religion was the cornerstone of both traditions, but each region approached it differently.

In Italy, spirituality was expressed through grandeur. Churches commissioned altarpieces that required enormous narrative clarity and heroic scale. The aim was to create a gateway between earthly and divine realms. The sacred was theatrical, dramatic, and architecturally staged. Collectors often encounter fragments of such altarpieces, perhaps a panel of a single saint or a predella scene, that still pulse with the original monumentality of the whole structure.

In the North, spirituality entered the home. Devotional diptychs, small portraits of donors praying before the Virgin, and scenes of Christ emerging within a meticulously rendered bourgeois interior created a form of private, contemplative worship. These works were meant not to overwhelm but to accompany daily life. Their religious symbolism was woven into the rhythms of ordinary existence, and their small scale allows more collectors today to engage with them intimately.

Understanding this distinction helps collectors anticipate the emotional weight of each work: Italian paintings aspire to transcendence, while Northern works cultivate spiritual intimacy.

Materials and Techniques: What Collectors Must Know

Italian painters in the early Renaissance used tempera on wooden panels, a medium that created luminous but matte surfaces. When oil slowly replaced tempera, Italian artists employed it in broader, more sculptural strokes designed for monumental clarity. Their pigments tended toward warm, earthy tones, creating a sense of sunlit solidity.

Northern painters used oil from the outset as their primary medium. Their approach was based on thin, translucent glazes layered in meticulous succession, building depth so crystalline that objects appear almost touchable. Their palettes captured the cool northern light, icy blues, deep greens, silvery reflections, which gives their works a distinct atmospheric chill.

Collectors studying Renaissance works must develop an eye for the surface quality: the smooth, glasslike finish of Northern paintings versus the subtly more textural and volumetric handling of Italian oils.

Market Realities and Collector Considerations

The market for Italian Renaissance art remains highly competitive. Surviving works by major names, Botticelli, Lippi, Mantegna, or Raphael’s circle, are almost exclusively confined to museums or blue-chip collections. Even workshop pieces, follower works, or fragments of lost altarpieces carry significant value because they represent the foundational canon of Western art.

Northern Renaissance works, while also rare, appear more frequently at auction because of the region’s prolific output and the durability of oil as a medium. Collectors can find superb works from schools influenced by van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, or Memling that reveal extraordinary craftsmanship at more accessible prices than their Italian counterparts. For serious collectors, the Northern market offers a pathway to museum-quality works without the stratospheric costs of Italian masterpieces.

How Northern Baroque Diverged from the Italian Tradition

To understand Northern Baroque art, one must first grasp how profoundly the Renaissance shaped each region. In Italy, the shift from Renaissance to Baroque intensified the theatricality that had always been present. Caravaggio, Bernini, and their successors transformed religious imagery into emotional drama, sculpting scenes with violent contrasts of light and shadow. The Italian Baroque was muscular, dramatic, and heroic; its aim was persuasion and sensory immersion.

Northern Baroque art, however, took a different path shaped by cultural, religious, and political forces. The Reformation had shattered the Northern artistic ecosystem. Many regions rejected large religious images, forcing painters to explore new subjects: still lifes, domestic interiors, landscapes, and scenes of everyday life. Baroque dynamism entered the North not through heroic drama but through an expanded sense of realism, atmosphere, and social narrative.

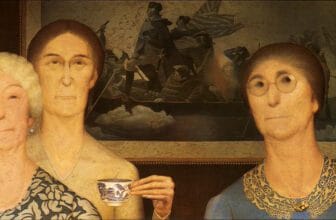

Dutch Golden Age painting exemplifies this shift. Rembrandt, Vermeer, Frans Hals, and countless others transformed the Baroque aesthetic into an exploration of psychological depth, luminous interiors, and the poetry of ordinary existence. Their works contain movement, but it is not theatrical movement; it is the quiet pulse of life.

Meanwhile, Flemish artists such as Rubens embraced a synthesis of Italian dynamism and Northern sensuality. Rubens used vigorous brushwork, monumental compositions, and mythological grandeur, yet retained the Northern delight in surface and richness. His workshop became a powerhouse that blended the two traditions in one of the most influential artistic enterprises in Europe.

Thus, the major difference between Northern and Italian Baroque lies in focus. Italian Baroque art seeks grandeur, persuasive emotion, and a heightened theatricality intended for churches and public spaces. Northern Baroque art explores atmosphere, realism, and the human condition within domestic, urban, or natural settings.

Collectors today can feel this divergence viscerally. A Caravaggio follower’s work radiates a fierce, chiaroscuro-driven intensity, while a Dutch Baroque painter draws the viewer into a world of everyday truth rendered with incomparable tenderness.

Why These Differences Still Matter for Collectors Today

Collecting Renaissance or Baroque art is not merely about aesthetic preference. It is about choosing between visions of the world. Some collectors are drawn to the monumental clarity and classical harmony of the Italian tradition, seeing in it the intellectual architecture of Western civilization. Others gravitate toward the minute beauty, atmospheric subtlety, and symbolic richness of the Northern schools.

Understanding the differences in technique, cultural context, and visual priorities allows collectors to make informed decisions about authenticity, condition, and value. An Italian work will likely show a focus on idealized anatomy and balanced spatial composition; a Northern work will reveal a mastery of surface, reflection, and the psychological intimacy of everyday life.

Market trends reflect these distinctions. Italian Renaissance works, rare and deeply tied to the canon, continue to command extraordinary prices. Northern works, while also highly valued, offer a broader range of entry points and remain accessible for private collectors seeking museum-grade objects.

Two Paths Toward Beauty, One Golden Era for Collectors

The Renaissance was not a single rebirth but a pair of intertwined revolutions, each shaped by its own geography, philosophy, religious climate, and artistic tools. Italy rediscovered antiquity and built a new visual world on the foundation of classical ideals. The North embraced the tangible, the intimate, and the symbolic, crafting images of extraordinary realism and emotional depth. Their legacies continued into the Baroque era, diverging even more dramatically as each region adapted to new spiritual and political realities.

For collectors, the journey between these worlds is endlessly rewarding. Italian Renaissance art offers the grandeur of human aspiration; Northern Renaissance art offers the poetry of human existence. To engage with both is to experience the full spectrum of European artistic genius during one of history’s most transformative eras.

If you build a collection that includes representatives from each school, you will not simply acquire beautiful objects, you will curate two fundamentally different ways of understanding the world, and two extraordinary visions of what it means to be human. image/