Marie Antoinette and Her Children Painting

In the opulent world of 18th-century France, where the brilliance of the monarchy dazzled the court and the cries of the common people echoed beyond palace walls, one painting attempted to bridge the ever-widening gap between queen and country. This was the iconic Marie Antoinette and Her Children, an ambitious royal portrait painted by Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun in 1787. At first glance, it may appear simply as a maternal image of the controversial queen surrounded by her offspring, but a deeper look reveals a masterstroke of political messaging, public relations, and emotional storytelling.

To fully appreciate the power and poignancy of this painting, one must delve into its origins, symbolism, composition, and historical significance. It is not only a reflection of a family, but also a mirror held up to a troubled France, a testament to royal desperation, and a document of a world on the brink of revolution.

The Artist Behind the Masterpiece: Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

The painting Marie Antoinette and Her Children was created by Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, one of the most accomplished female painters of the 18th century. Born in 1755, Vigée Le Brun rose to prominence at a time when few women were accepted in the formal art world. Her talent, charm, and connections, however, earned her a rare place as a portraitist at the royal court of Louis XVI.

She became a favorite of Marie Antoinette, who admired her style, elegance, and ability to capture not only physical likenesses but also subtle psychological depth. Vigée Le Brun painted the queen more than 30 times, creating some of the most enduring images of her reign. Yet, none carried the same weight, politically and emotionally, as Marie Antoinette and Her Children.

The painting was commissioned in 1785 and completed in 1787 during a time of growing hostility toward the monarchy. Marie Antoinette, born an Austrian archduchess and married into the French royal family at 14, had become a figure of deep controversy. Branded by pamphleteers as frivolous, foreign, and wasteful, epitomized by the (likely apocryphal) quote, “Let them eat cake”, the queen’s public image had deteriorated dramatically.

One of the most notorious events leading to this commission was the Affair of the Diamond Necklace, a scandal in 1785 involving a fraud perpetrated in her name. Though Marie Antoinette was innocent, public opinion was further poisoned. In response, the royal court sought to rehabilitate her image through more strategic, emotionally resonant portraiture.

Thus, Marie Antoinette and Her Children was conceived not as mere family documentation but as a public relations tool, a visual rebuttal to her perceived vanity and detachment.

What’s Happening in the Painting?

In Marie Antoinette and Her Children, the queen is seated in regal but modest attire, positioned in a triangular composition reminiscent of religious depictions of the Madonna and Child. She is surrounded by her three living children: Marie-Thérèse Charlotte (Madame Royale) standing to her left; the Dauphin Louis-Joseph, her eldest son, leaning affectionately against her; and Louis-Charles (later known as Louis XVII) seated in her lap.

A poignant element of the painting is the empty cradle to Marie Antoinette’s right, a symbolic tribute to Sophie-Hélène-Béatrix, the queen’s youngest daughter who died in infancy shortly before the painting’s completion. The inclusion of the empty cradle humanized the queen by portraying her grief, positioning her as a suffering mother rather than a heartless monarch.

Behind her, a canopy frames the scene, suggesting the royal bedchamber or nursery. Luxurious, but not ostentatious, the setting tempers the queen’s aristocratic image with maternal intimacy. Notably, Marie Antoinette wears no crown, jewels, or extravagant finery, only a red velvet gown and a simple headdress, underscoring a message of simplicity and virtue.

Another critical symbol in the painting is the jewel cabinet to the left, subtly referencing the regalia of the monarchy, while the queen’s pose and gentle gaze convey serenity, strength, and grace. Each of these elements was meticulously arranged to create a portrait that spoke not just to the nobility, but to the people of France.

Genre and Artistic Style

The painting is a formal state portrait, yet it merges elements of history painting, religious iconography, and genre painting (scenes of everyday life) to convey layered meanings. It falls within the Neoclassical style, which favored clarity, order, and classical ideals of heroism and morality, an aesthetic favored in the waning days of the Ancien Régime.

Vigée Le Brun’s technique blends academic precision with warmth and realism, allowing for both idealization and intimacy. The composition borrows heavily from religious works, particularly the Renaissance depictions of the Holy Family, evoking comparisons between Marie Antoinette and the Virgin Mary, a calculated yet bold move to rehabilitate her image.

The painting also anticipates Romanticism in its emotional appeal, especially in the use of children and the empty cradle as symbols of vulnerability and maternal love.

The Painting’s Reception and Historical Impact

Marie Antoinette and Her Children was first exhibited at the Salon of 1787, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris. The painting was meant to counteract the wave of vitriol that had been directed toward the queen and showcase her as a model of virtue, femininity, and maternal devotion.

However, the reception was mixed. Supporters of the monarchy praised the painting’s elegance and emotional depth, but many critics saw it as transparent propaganda. For a public increasingly agitated by inequality and famine, no image, no matter how skillfully painted, could erase their anger at the monarchy’s perceived failures.

Nonetheless, the painting remains a significant artifact of pre-revolutionary France, capturing the moment when visual culture and political messaging collided.

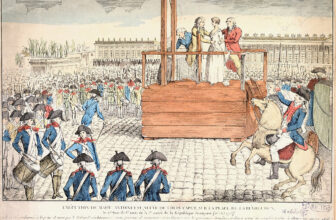

Tragically, any attempt to humanize the queen through art proved futile. Just two years later, in 1789, the French Revolution erupted. The monarchy would collapse, and Marie Antoinette would be executed in 1793 after a humiliating trial. Her children, once symbols of hope, would suffer tragic fates: the dauphin Louis-Joseph died of tuberculosis in 1789, and Louis-Charles (Louis XVII) perished in captivity in 1795. Only Marie-Thérèse survived the revolution.

Where is the Painting Today?

Today, the original Marie Antoinette and Her Children is housed at the Château de Versailles, the very palace where the queen once lived in extravagant splendor. The painting is on display in the Queen’s State Apartments, serving as a poignant reminder of the woman behind the crown.

The painting is now viewed not as propaganda, but as a historical document, a frozen moment in time reflecting the complex intersection of politics, art, motherhood, and tragedy. Art historians, visitors, and scholars continue to examine it not only for its artistic merits but for the profound story it tells of a queen’s last attempt to connect with her people through imagery.

The Legacy of the Painting and Its Artist

The enduring legacy of Marie Antoinette and Her Children owes much to the genius of Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, who managed to balance royal formality with genuine human emotion. Despite the political collapse of the monarchy, Vigée Le Brun continued her career across Europe, painting nobility and aristocrats in Italy, Austria, and Russia. She eventually returned to France and lived to the age of 86.

Her memoirs, published in the 1830s, give rare insights into her life at court and her close relationship with Marie Antoinette, whom she described with warmth and admiration.

As for the painting, its relevance has only grown. In modern times, it has been the subject of exhibitions, books, documentaries, and films. It continues to evoke discussion about the power of images, especially in shaping or reshaping public opinion in times of crisis.

More Than a Portrait

Marie Antoinette and Her Children is far more than a family portrait; it is a complex political statement, a symbolic composition, and an emotional appeal wrapped in artistic mastery. Created during one of the most turbulent periods in French history, it sought to repair a broken image with the tools of empathy and maternal symbolism.

While it failed to save the queen or the monarchy, the painting succeeded in capturing a fleeting moment of vulnerability and hope. It stands today not only as a representation of a bygone royal family but also as a timeless reflection on image-making, motherhood, and the power of visual storytelling in the face of public scrutiny.

Whether viewed as a masterpiece of art, a relic of royal propaganda, or a portrait of maternal devotion, Marie Antoinette and Her Children remains one of the most compelling works of 18th-century European art, a canvas that continues to speak across centuries.