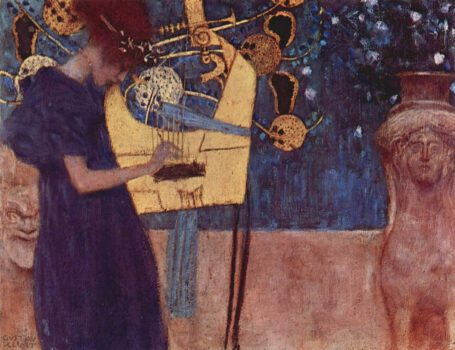

Meaning of Music Painting by Gustav Klimt

In the still air of Vienna at the cusp of the 20th century, the world was changing. Empires stood firm on fragile legs, the philosophy of Freud began to pierce the human soul, and art, as if echoing the restlessness of a new age, began to shed its skin. Amid this transformation stood Gustav Klimt, a master of sensuality, symbolism, and allegory. His brush worked not merely with pigment but with metaphor and myth. One of his earlier yet deeply evocative works, “Music” (1895), encapsulates this transformative spirit and offers viewers a meditative reflection on the intangible force that is music.

Though it is often overshadowed by Klimt’s later golden masterpieces like The Kiss or Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, Music is a keystone painting. It does not shine with gold leaf or dazzle with erotic flamboyance. Instead, it whispers, drawing us into an internal world where music, death, and the eternal feminine converge. This is the story of Music by Gustav Klimt, how it was painted, what it represents, the symbolism it holds, and where it lives today.

The Painting: Composition and Visual Description

Music is a vertically elongated canvas, modest in size and subtle in palette. Dominated by a solitary female figure holding a lyre, the painting evokes the poise of an ancient Greek muse. She is frontal, solemn, and quietly powerful. Her expression is serene yet detached, lost, perhaps, in the realm of sound we, the viewers, cannot hear. This silent reverie becomes the central mystery of the painting: what is she hearing, and what is she feeling?

Behind her to the right is a sculpted mask, seemingly an antique funerary figure, its mouth agape, its form rigid in contrast to the woman’s softness. This juxtaposition between life and death, music and silence, immediacy and eternity, becomes the axis on which the painting turns.

Though the palette is limited, warm earthy tones, pale flesh, golden browns, the painter’s mastery of surface and form gives it immense depth. The textures are not yet the elaborate decorative fields Klimt would later become famous for, but they hint at his coming style. Drapery folds around the muse’s body in soft rhythmic waves, echoing the music she plays.

How Music Painting Was Painted: Techniques and Influences

Created in 1895, Music belongs to Klimt’s early Symbolist period. At this time, he was still moving away from the classical academic art of his youth and toward the more idiosyncratic, dreamlike art that would define the Vienna Secession. The brushwork is relatively restrained, tight and smooth in the rendering of skin and facial features, looser and more expressive in the treatment of the background and clothing.

Klimt uses a mix of oil on canvas and a nearly monochrome palette to suggest a world of inward contemplation. While the brush does not leave dramatic textures, its control over light and shadow evokes a sculptural quality, especially in the woman’s neck and the lines of her robe.

Notably, Klimt was influenced by Classical antiquity during this time, particularly Greek and Roman statuary, and this is evident in the pose of the woman and the prominence of the lyre. He was also increasingly drawn to Symbolism, a European art movement that aimed to represent ideas, emotions, and metaphysical concepts through allegory and symbol, rather than direct representation. The solemn muse and the funerary mask suggest this symbolic turn.

What “Music” Painting Represents

But what, exactly, is happening in Music?

On the surface: a woman plays the lyre. But Klimt never deals in surfaces alone. The scene is not an event, but an allegory. The lyre player is not a real woman, but rather a personification of music itself, an eternal muse caught in the act of creation, or perhaps transmission, channeling something beyond human.

The painting’s deeper significance lies in this dichotomy between the sensual and the eternal. Music is an ephemeral force, it exists in time, and then it disappears. It affects the body, moves the spirit, but cannot be held. Klimt gives this transitory force a form: the woman. Her expression is not one of rapture, but of solemn absorption. She does not revel in the music; she becomes it.

And then there is the death mask. In the background, the funerary sculpture stares blankly ahead, lifeless and immutable. This contrast underscores the paradox of music, it lives only in the moment of performance. When it ends, silence resumes. The mask may also hint at the Greek tragedy, where music and death were often interlinked. In ancient plays, the chorus and the lyre accompanied stories of fate and demise. Here, Klimt resurrects that theatricality, suggesting that behind every act of beauty lies an echo of mortality.

Symbolism in “Music” Painting by Gustave Klimt

Symbolism in Klimt’s work often involves layers of myth, sexuality, life, and death. In Music, these symbols are more restrained but no less potent.

1. The Lyre

The lyre is not just a musical instrument; it is a classical symbol of Apollo, the Greek god of music, poetry, and prophecy. In mythology, the lyre’s sound could calm storms, tame wild beasts, and move the hearts of gods. In Klimt’s hands, the lyre becomes a conduit between the mortal and the divine, a tool that allows the muse to access otherworldly realms.

2. The Female Muse

As in many Klimt works, the female figure is both the subject and the symbol. She is not a performer but a vessel of meaning. Her stylized posture, elongated neck, and detached gaze place her outside of ordinary reality. She is not playing music for anyone. Instead, she is an embodiment of music as a metaphysical force, seductive, aloof, eternal.

3. The Funerary Mask

Most mysterious is the sculptural mask behind her. Scholars have debated its meaning: is it a symbol of death? A silent witness? A relic of forgotten civilizations? Perhaps it is all of these. It reminds us that music exists in opposition to silence, and that even the most divine sound will ultimately fade into quiet. It also evokes the idea of the eternal audience, that which observes art long after its creator has perished.

4. Color and Tone

Though Klimt would later become synonymous with gold and lavish ornamentation, here he uses muted ochres and browns to evoke the melancholy of sound. The warm tones offer sensuality, but their restraint reflects the painting’s introspective theme.

Philosophical and Emotional Interpretation

Music is an exploration of the tension between ephemerality and eternity, flesh and spirit, art and death. Music, like life, is beautiful because it does not last. And like art, it serves as a bridge between the body and the soul.

The woman is caught in a moment of transcendence, she exists neither fully in the world nor fully beyond it. Her music reaches into the metaphysical, yet her body remains grounded in the material realm. The funerary mask watches as a reminder of what comes after. It is not a threat, but a fact, a quiet observer of the living.

This meditation on the fleeting nature of beauty and sound connects Music to wider themes in Symbolist art. It also prefigures the themes of death, eroticism, and transcendence that would dominate Klimt’s later work.

Type of Art and Art Historical Context

Music is a quintessential Symbolist painting. Emerging in the late 19th century, Symbolism rejected realism and naturalism in favor of conveying the inner truths of the human experience, dreams, emotions, ideals, and fears.

Unlike Impressionism, which sought to capture light and external experience, Symbolism was inward-looking. Klimt, though not always categorized strictly as a Symbolist, was deeply influenced by this movement.

The painting also exhibits elements of Art Nouveau, the sinuous lines and stylized forms hinting at the decorative language Klimt would develop in his golden period. However, it predates the founding of the Vienna Secession (1897), which Klimt co-founded. In this way, Music acts as a transitional work, straddling academic classicism and the modernist revolution to come.

Current Location of “Music” Painting

Today, Music is part of the collection of the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere in Vienna, Austria. The Belvedere is home to one of the world’s greatest collections of Klimt’s work, including The Kiss and Judith. The painting occasionally travels as part of exhibitions but remains rooted in the city that gave Klimt his voice.

Its presence in the Belvedere places it in context alongside his later, more famous works, allowing visitors to trace the evolution of Klimt’s style, themes, and symbolic language.

A Solitary Masterpiece

Music by Gustav Klimt is not loud. It does not seduce with gold or dazzle with eroticism. Instead, it whispers. It invites you to lean in, to pause, to feel. It stands at the intersection of life and death, flesh and spirit, art and silence.

In an age where art often shouts to be seen, Music reminds us of the power of restraint. It evokes a sound we cannot hear but somehow still feel. It transforms a visual experience into an emotional and philosophical one. And in doing so, it achieves what great art always strives for, to transcend medium and speak to something essential and eternal.

Gustav Klimt’s Music is not just a painting. It is an echo, a reverberation, a moment suspended between time and eternity. And in that suspended moment, we find ourselves, listening.