The Annunciation with Saint Emidius Symbolism and Meaning

Few paintings from the Italian Renaissance capture the marriage of divine mystery, civic pride, and painstaking craftsmanship quite like Carlo Crivelli’s The Annunciation with Saint Emidius (1486). This extraordinary work, housed today in the National Gallery, London, stands as one of the most fascinating interpretations of the Christian Annunciation scene. With its jewel-like colors, architectural detail, and layering of sacred symbolism with earthly pride, it is both an object of devotion and a historical testament to the aspirations of its time.

To truly understand the painting, one must not only look at its religious subject matter but also at the society and patronage that shaped its creation, the artistic style of Carlo Crivelli, and the meanings hidden within its ornate surfaces. This essay will explore the background, symbolism, and significance of The Annunciation with Saint Emidius, unpacking what makes it one of the most intriguing Renaissance paintings ever produced.

Who Painted It: Carlo Crivelli

Carlo Crivelli (c. 1430–c. 1495) is often described as one of the more eccentric figures of the Italian Renaissance. Unlike the better-known giants of his time, such as Botticelli, Leonardo, or Raphael, Crivelli carved out a distinctive path, largely working in the Marche region of central Italy rather than in the great artistic capitals like Florence or Rome.

Crivelli’s style was characterized by meticulous detail, rich ornamentation, and a blend of Gothic traditions with Renaissance innovations. He had a fascination with textures, surfaces, and decorative effects, gold brocades, fruits, festoons, and jewels appear frequently in his works, turning them into dazzling displays of craftsmanship as well as devotional icons.

Whereas many Renaissance artists pursued naturalism and spatial harmony, Crivelli leaned toward stylization and theatricality. His figures are elongated, his spaces complex and sometimes contradictory, and his surfaces shimmer with gold leaf. This gave his paintings an almost otherworldly, dreamlike quality.

By the time he painted The Annunciation with Saint Emidius in 1486, Crivelli had developed into a mature master, commanding important commissions and enjoying favor with civic and religious authorities. This particular painting was commissioned for the Church of the Holy Annunciation in the small town of Ascoli Piceno, in the Marche region, a place proud of its history and its religious devotion.

How The Annunciation with Saint Emidius Was Painted

Crivelli painted The Annunciation with Saint Emidius using tempera and oil on wood, a technique common in the 15th century. Tempera, made by mixing pigments with egg yolk, allowed for brilliant, jewel-like colors and precise detail. Oil, which was still relatively new in Italian art at the time, gave added depth and richness to certain passages.

The panel itself is large, over two meters tall, intended to command attention in a church setting. Crivelli’s characteristic use of gilding, trompe-l’œil effects, and ornate architectural framing would have made the painting appear like both a window into a sacred event and a glittering, luxurious object.

One striking technical feature is Crivelli’s use of perspective. He employs linear perspective to construct a believable architectural space, yet he also subverts it, filling the composition with details and cutaways that seem more decorative than strictly rational. His interest was less in perfect mathematical order (as with Brunelleschi or Piero della Francesca) and more in creating a visually rich, almost theatrical staging of the divine drama.

What is Happening in The Annunciation with Saint Emidius

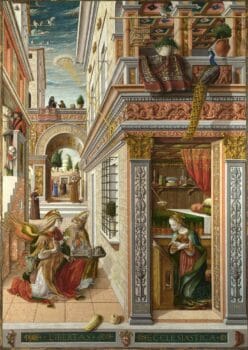

The Annunciation with Saint Emidius depicts the familiar biblical scene of the Annunciation, the moment when the Angel Gabriel appears to the Virgin Mary to announce that she will bear the Son of God. Yet Crivelli complicates the narrative by embedding it within a highly detailed urban setting, full of symbolic and civic references.

On the left side of the painting, the Angel Gabriel kneels in the street, accompanied by Saint Emidius, the patron saint of Ascoli Piceno. Emidius, dressed as a bishop, holds a model of the city in his hands, a common motif in Renaissance art when a saint is shown presenting a town under their protection.

Above, a golden ray of light descends from the heavens, carrying the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove. The ray penetrates through an open window and into the small chamber where Mary kneels in prayer, receiving the message. She is enclosed within a domestic, urban setting, reinforcing the idea of the divine entering the everyday world.

Around the scene, details abound: fruits hang from garlands, a peacock perches on a ledge, townspeople go about their business in the background, and architectural details are lavishly rendered. The whole work feels like a tapestry of sacred and earthly life intertwined.

What is The Annunciation with Saint Emidius Represents

At its core, the painting represents the Incarnation, the mystery of God taking human form through Mary. Yet in Crivelli’s interpretation, the Annunciation is not just a private, spiritual moment; it is also a civic event. By including Saint Emidius and the city of Ascoli Piceno, Crivelli emphasizes that the divine blessing extends not just to Mary but to the entire community.

The painting can thus be read as both a religious icon and a political statement. It reflects the pride of Ascoli Piceno, which had recently received papal privileges from Pope Sixtus IV. Including Saint Emidius with the model of the city was a way of asserting both spiritual protection and political legitimacy.

In this sense, The Annunciation with Saint Emidius is as much about the relationship between heaven and Ascoli as it is about Mary’s encounter with Gabriel. The divine message sanctifies not just the Virgin’s womb but also the civic identity of the town.

The Annunciation with Saint Emidius Symbolism and Meaning

Crivelli’s painting is rich with symbolism, much of it rooted in traditional Christian iconography but deployed with his characteristic flair.

The Ray of Light and Dove: The golden ray descending from the sky, carrying the Holy Spirit, represents divine intervention and the miraculous conception. The straight line of light cutting across the scene visually connects heaven and earth.

Mary’s Enclosed Chamber: The Virgin is shown within an enclosed space, symbolizing her purity and virginity. The idea of the “hortus conclusus” (enclosed garden) was a common metaphor for Mary in medieval and Renaissance art.

Saint Emidius with the City Model: Emidius, martyred in the early 4th century, is the patron saint of Ascoli. His presence, holding a model of the city, symbolizes his protection over the town and its citizens. This insertion localizes the universal story of the Annunciation, binding it to Ascoli’s identity.

Fruits and Vegetables: Crivelli often included still-life details, and here one finds apples, cucumbers, gourds, and other produce. These can carry multiple meanings: the apple for original sin, the cucumber for resurrection, the gourd for eternal life. They also reinforce the sense of abundance and divine blessing.

Peacock: Perched on a balustrade, the peacock is a symbol of immortality, as its flesh was believed in medieval times to resist decay. It also represents Christ’s resurrection.

Urban Setting: Unlike earlier Annunciations set in pastoral or abstract spaces, Crivelli situates the event in a bustling Renaissance city. This suggests that the divine can enter even the ordinary rhythms of daily life.

Trompe-l’œil Details: Crivelli delights in creating the illusion of real objects, garlands, shadows, ledges, breaking the boundary between painting and viewer. This reminds the audience that the sacred is not distant but immediate and tangible.

What Type of Art Is The Annunciation with Saint Emidius

The Annunciation with Saint Emidius is an example of Renaissance panel painting, yet it retains strong ties to Gothic traditions. It embodies several key characteristics of 15th-century Italian art:

Religious Subject Matter: Like most Renaissance works, its primary function was devotional. It was created for a church and intended to inspire prayer and contemplation.

Use of Perspective: Crivelli employs linear perspective to create depth, although he bends the rules in ways that reveal his decorative priorities.

Integration of Civic Identity: The inclusion of Saint Emidius and the model of Ascoli reflects a Renaissance tendency to blend religious art with civic pride.

Ornamentation and Detail: Crivelli’s use of tempera, gold leaf, and elaborate still-life details links him to the International Gothic style, even as he worked within Renaissance frameworks.

Thus, the painting sits at a crossroads: it is both Renaissance in its perspective and civic symbolism, and Gothic in its ornamental richness and mystical quality.

Where the The Annunciation with Saint Emidius Is Today

Today, The Annunciation with Saint Emidius resides in the National Gallery, London, one of the museum’s most celebrated Italian Renaissance works. It was acquired in the 19th century, during a period when British collectors and institutions were eagerly acquiring Italian masterpieces.

For visitors, the painting remains a highlight not only because of its dazzling craftsmanship but also because of its unusual combination of sacred and civic elements. It is often reproduced in books on Renaissance art, serving as a prime example of how regional painters like Crivelli contributed to the diversity of Renaissance visual culture.

What Is Happening in The Annunciation with Saint Emidius

To fully appreciate Crivelli’s work, one can follow the painting almost like a narrative unfolding in multiple registers:

The Divine Intervention: At the very top, God the Father sends forth a golden ray of light, in which the Holy Spirit dove travels, symbolizing the Incarnation.

The Angel’s Arrival: Gabriel kneels on the left, his elaborate wings and flowing garments emphasizing the celestial nature of his mission. He points toward Mary, addressing her with the words of the Annunciation.

Saint Emidius’s Role: Beside Gabriel, Saint Emidius joins in the procession, holding the model of Ascoli. This connects the heavenly message with earthly politics and local devotion.

Mary’s Response: Inside her chamber, Mary is caught in prayer, surprised by the intrusion of divine light. Her humility and acceptance are central to the scene.

Civic and Daily Life: Around the central drama, everyday details abound: figures lean from windows, townspeople move about, architectural details frame the event. These create a sense that the divine permeates ordinary reality.

Why The Annunciation with Saint Emidius Painting Matters

The Annunciation with Saint Emidius is not just a religious painting; it is a cultural artifact that reveals how Renaissance towns saw themselves in relation to the divine. By embedding the universal story of the Annunciation within the specific civic identity of Ascoli Piceno, Crivelli created a work that functioned on multiple levels: devotional, political, and aesthetic.

It demonstrates how Renaissance art was not monolithic, while Florence and Rome pursued idealized harmony and naturalism, artists like Crivelli in the provinces developed their own highly distinctive approaches. His blend of Gothic ornament, Renaissance perspective, and symbolic richness makes him a unique voice within the era.

Most of all, the painting invites viewers into a layered vision of reality, where heaven and earth meet, where divine mysteries unfold within the streets of a Renaissance town, and where art itself becomes a bridge between the sacred and the civic.

Carlo Crivelli’s The Annunciation with Saint Emidius stands as one of the most fascinating interpretations of the Annunciation theme in Renaissance art. Painted in 1486 for the Church of the Holy Annunciation in Ascoli Piceno, it combines meticulous craftsmanship, symbolic richness, and civic pride.

Through its interplay of sacred narrative and local identity, it reveals how art in the Renaissance was both a medium of devotion and a reflection of communal aspiration. Today, as it hangs in the National Gallery in London, it continues to captivate viewers with its jewel-like detail and profound layers of meaning, a reminder of the enduring power of art to bind heaven and earth, mystery and history, devotion and pride.