What Is The Golden Age Painting All About

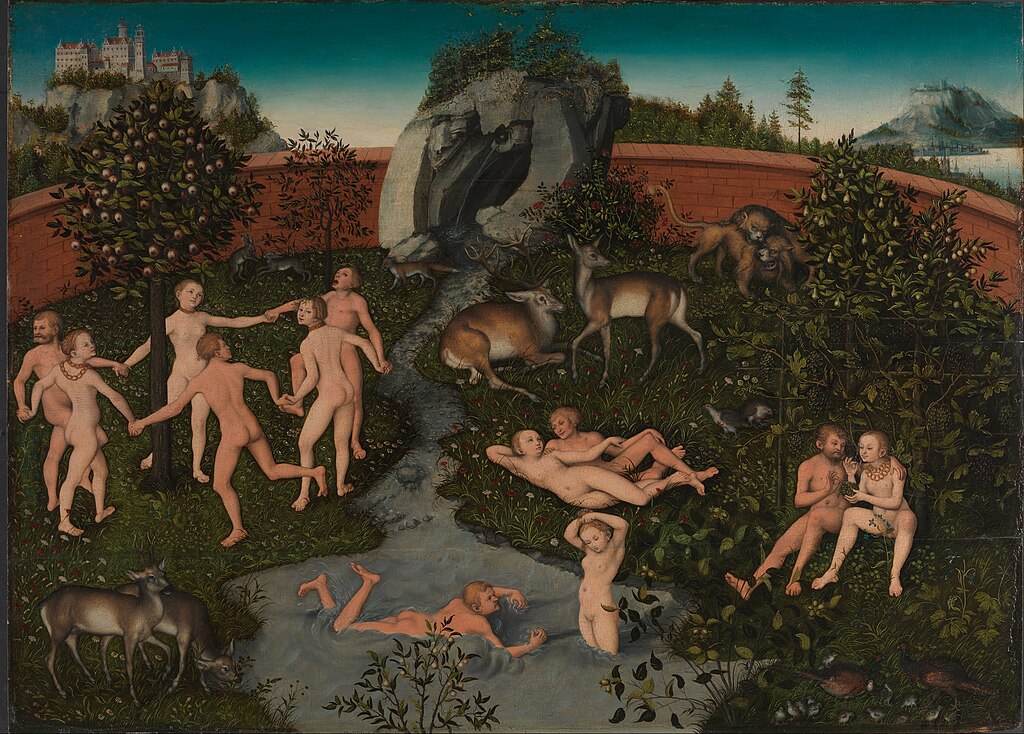

When we think of the German Renaissance, few artists shine as brightly as Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553). A close friend of Martin Luther and a key figure of the Reformation era, Cranach was known for his lush, detailed paintings and his ability to balance humanist ideals with religious themes. Among his many celebrated works, one that stands out for its philosophical depth and aesthetic complexity is “The Golden Age”, a serene, yet symbolically rich painting that offers a window into an idealized world, unmarred by conflict, hierarchy, or toil.

Painted in 1530, The Golden Age is not simply a visual feast of mythological beauty; it is a profound commentary on paradise lost, human nature, and the longing for a utopian past. This post unravels the layers of this magnificent work, exploring who painted it and how, what it represents, and why it remains an important artifact in both art history and philosophical discourse.

Who Painted The Golden Age and How?

Lucas Cranach the Elder was a prolific German painter and printmaker who flourished during the transition from the Gothic to the Renaissance style in Northern Europe. As court painter to the Electors of Saxony in Wittenberg and a friend of Martin Luther, Cranach’s studio was known for its remarkable output and stylistic consistency.

“The Golden Age” was created in 1530, during Cranach’s mature period. By this time, he had already mastered a signature style characterized by elongated figures, refined lines, and a unique fusion of the sacred and the secular. The painting was executed in oil on panel, a common medium of the time, allowing for a high level of detail, smooth layering, and vivid coloration.

While we know that Cranach ran a large workshop and sometimes delegated elements to apprentices or assistants, The Golden Age bears the hallmarks of his own hand, especially in the treatment of the figures and the harmony of the composition. It is likely that Cranach painted the main subjects himself and allowed studio assistants to contribute to the background or detailing under his close supervision.

At its core, The Golden Age is a pastoral fantasy, a representation of a mythical time of harmony between man, nature, and the divine. The idea of a “golden age” originates in classical antiquity, particularly in the works of Hesiod and Ovid, who described an early era of humankind marked by peace, abundance, and innocence, before the decline into the subsequent Ages of Silver, Bronze, and Iron.

Cranach reinterprets this classical theme within the moral and philosophical framework of the Renaissance. The painting presents coverless body figures, men, women, and children, living in perfect harmony in a lush, green landscape. There is no hint of shame or labor; instead, the figures are portrayed as completely integrated with nature. They lounge beneath trees, dance, converse, and enjoy the fruits of the earth in a relaxed, unstructured community.

The scene reflects a longing for innocence and unity, an age before the Fall of Man or the complications of modern life. It is an imagined paradise that transcends religious, mythological, and philosophical boundaries.

Symbolism and Meaning: A World Without Sin

1. Forbidden Gathering and Innocence

One of the most striking aspects of the painting is the careless privacy of its figures. In Renaissance art, cover less body often carried complex meanings, it could be symbolic of purity, vulnerability, or even sin. In The Golden Age, however, it is a symbol of innocence. These figures are not ashamed or eroticized; they are natural, content, and unburdened by the social conventions that would later impose clothing and hierarchy.

The scene harks back to Adam and Eve before the Fall, a common allegory for the ideal state of humanity. Cranach’s figures are free from shame, competition, or domination, reflecting the theological concept of a prelapsarian world, before sin entered the human condition.

2. Harmony with Nature

The landscape is rich with green meadows, gentle hills, and flowering trees, symbolizing a fertile and benevolent nature that provides for all without requiring toil. The people are shown gathering food, not working the land. This references the classical ideal that in the Golden Age, “the earth gave forth its fruit without ploughing or sowing.”

Animals coexist peacefully with humans, deer graze alongside the people, birds flit above, and there is no sense of fear or predation. This peaceful coexistence reflects a natural order free from violence, a world where instinct and reason are aligned.

3. The Circle and Cyclical Life

A particularly symbolic element is the circular formation of some of the dancing figures. Circles in art often symbolize eternity, unity, and balance. Here, the circular movement suggests an eternal return to simplicity and joy, echoing the ancient belief that the world moves in cycles and that the Golden Age might someday return.

4. Children and Rebirth

Children are seen playing and interacting with adults, suggesting renewal, fertility, and the perpetuation of innocence. In Renaissance philosophy, children were often seen as closer to the divine, untainted by society’s corruption.

5. Absence of Tools and Architecture

Notably, there are no tools, weapons, or buildings in the painting. This absence is a crucial part of the symbolism, there is no need for agriculture, conflict, or civilization. The scene is anti-urban, pastoral, and wholly integrated with nature. It reflects a longing for Arcadia, the mythic land of shepherds and serenity.

What Is Happening in the Painting?

Visually, The Golden Age is a bustling yet tranquil tableau. The painting doesn’t focus on a single central event but instead presents a panoramic scene full of interwoven vignettes:

A group of women lounges beneath a tree, chatting and resting.

Men and women dance in a circle in the middle ground, suggesting communal celebration.

Children frolic in the grass, adding a sense of life and movement.

Others gather fruit, lie in pairs, or gaze at the landscape.

In the background, a lake or river winds through the valley, inviting the viewer’s eye into the depths of the idyllic setting.

This composition reflects not a moment in time, but a state of being, a way of life marked by peace, joy, and ease. There are no rulers, no clergy, no divisions, just people living in harmony with each other and with the land.

What Type of Art Is The Golden Age?

The Golden Age is best classified as a Renaissance allegorical painting, with strong elements of mythological and humanist art. While it draws on classical themes, its execution and style are firmly Northern Renaissance.

Cranach’s unique style includes:

Fine linearity and precise contours (influenced by Gothic art)

Emphasis on decorative detail and naturalistic settings

Human figures with elongated limbs and idealized features

A tendency toward the allegorical and didactic

Unlike the Italian Renaissance, which often emphasized monumental architecture and mathematical perspective, the German Renaissance (and Cranach’s work in particular) focused more on symbolism, narrative, and moral meaning. The Golden Age is not just an aesthetic work, it is a visual philosophy.

The Cultural and Philosophical Context

In 1530, when this painting was created, Europe was undergoing seismic shifts, politically, religiously, and intellectually. The Protestant Reformation was challenging the Catholic Church, and humanist scholars were rediscovering the ancient philosophies of Greece and Rome.

Cranach was deeply involved in this intellectual climate. A friend and supporter of Martin Luther, he sought to portray alternative visions of human destiny, often contrasting the Biblical Fall with ideals of redemption or innocence.

The Golden Age, then, is more than nostalgia. It is a critique of the present and a yearning for a better world, a visual counterpart to Thomas More’s Utopia or Erasmus’s Praise of Folly. It embodies the tension between Renaissance optimism and Reformation morality.

Where Is The Golden Age by Lucas Cranach the Elder Located Today?

Today, “The Golden Age” is housed in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Old Masters Picture Gallery) in Dresden, Germany. The painting is part of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (Dresden State Art Collections), one of the oldest and most prestigious art institutions in Europe.

This gallery holds numerous works by Cranach and other Northern Renaissance artists, making it a key destination for those interested in early modern European art.

How Much Is The Golden Age by Lucas Cranach the Elder Worth?

As a piece held in a major public museum, The Golden Age is not on the market and has no public price tag. However, the value of Cranach’s paintings on the art market is substantial. Works by Lucas Cranach the Elder have fetched tens of millions of dollars at auction.

For instance, Cranach’s “The Bocca della Verità” sold for over $9 million at Sotheby’s in 2015. A unique, highly symbolic painting like The Golden Age, if hypothetically offered for sale, could be valued well into the $30–50 million range, due to its rarity, condition, and historical significance.

However, its true worth lies in its cultural and philosophical value, not its market price. As part of a national collection, it is priceless, a heritage piece meant for public enrichment rather than private ownership.

A Mirror to Lost Paradise

Lucas Cranach the Elder’s The Golden Age is not just a painting, it is a vision. It offers us a fleeting glimpse into a world of perfect harmony, free from strife, and filled with abundance. Its lush scenery, the painting, and idealized figures invite us to question the costs of modernity, hierarchy, and ambition.

At a time when Europe was split between religious upheaval and humanist revival, Cranach delivered a serene image of what might be possible, if only we could return to our innocent beginnings. The painting remains as relevant today as it was nearly 500 years ago, challenging us to reimagine what peace, simplicity, and community might look like.

In The Golden Age, we do not see a dream abandoned, but a dream preserved, one that continues to inspire, intrigue, and haunt the modern world.