What are Tullio Lombardo’s Most Famous Sculptures

In the marble-laden corridors of Renaissance Venice, one sculptor stood out, not merely for his technical prowess, but for the soul he breathed into stone. Tullio Lombardo (c. 1455–1532), often overshadowed by Michelangelo or Donatello, was a virtuoso whose sculptural poetry bridged the humanistic ideals of the High Renaissance with the architectural elegance of his native Venice.

Born into the esteemed Lombardo family of sculptors and architects, Tullio inherited not just a trade but a legacy. His father, Pietro Lombardo, was a master sculptor and architect who laid the foundations of the Lombardo dynasty. Under Pietro’s guidance, Tullio absorbed the technical discipline of sculpture, but it was his own vision, his marriage of classicism and emotional expression, that distinguished him.

What Is Tullio Lombardo Known For?

Tullio Lombardo is primarily known for marble sculpture, not just in the form of standalone figures but in elaborate funerary monuments and architectural reliefs that adorn churches and palaces across northern Italy. His work exudes an idealized, classical beauty reminiscent of Ancient Greece and Rome, but his innovation lies in the way he humanized that perfection.

He is considered a key figure in the transition between the Early Renaissance and High Renaissance in Venetian sculpture. While many of his contemporaries focused on Gothic conventions, Tullio embraced naturalism, symmetry, anatomical accuracy, and psychological subtlety. His sculptures are imbued with softness, warmth, and an introspective quality rare in the sculptural traditions of his time.

Tullio Lombardo’s Most Famous Sculptures

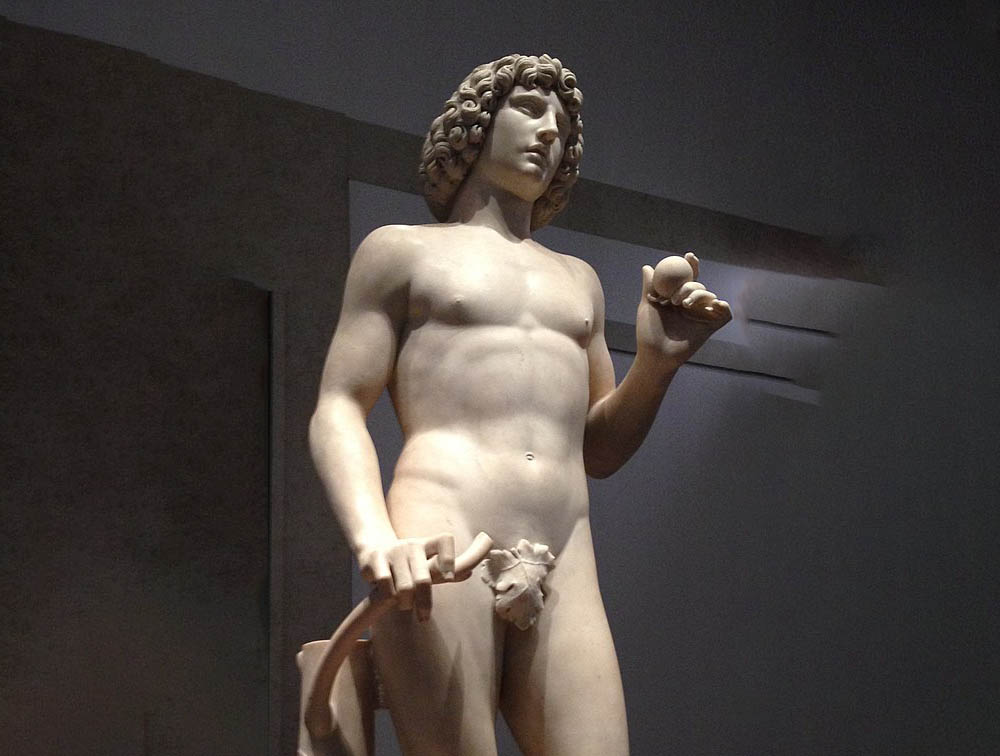

1. Adam (c. 1490–95)

Perhaps the most celebrated work of Tullio Lombardo is his life-size marble statue of Adam, originally part of the funerary monument of Doge Andrea Vendramin in the church of Santa Maria dei Servi in Venice.

Now housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, this sculpture is a stunning evocation of the ideal male nude, clearly influenced by classical antiquity. The contrapposto pose, the defined musculature, and the calm, introspective gaze recall ancient Greek statuary, particularly the works of Praxiteles and Polykleitos.

What makes Adam revolutionary is its human fragility. Unlike Michelangelo’s David, which is tense and heroic, Lombardo’s Adam is softer, thoughtful, on the cusp of temptation, vulnerable, and subtly aware of the monumental role he plays in the biblical story. This psychological nuance set Tullio apart.

Interestingly, the sculpture suffered a devastating accident in 2002 when it fell from its pedestal and shattered into more than 28 pieces. The Met’s decade-long restoration project, completed in 2014, became a landmark in art conservation. It was the first time such sophisticated techniques, such as 3D modeling and computer simulations, were used to restore a Renaissance marble sculpture.

2. Funerary Monument of Doge Andrea Vendramin (c. 1493–95)

Commissioned for the final resting place of the Venetian Doge Andrea Vendramin, this funerary monument is a masterpiece of sculptural architecture. A collaboration with his father Pietro and brother Antonio, Tullio’s contributions are particularly evident in the expressive reliefs and figures.

Located today in the Church of San Giovanni e Paolo in Venice, this monument is both a celebration of the deceased and a triumph of Renaissance humanism. The combination of classical figures, rich iconography, and harmonious architectural elements reflects Tullio’s deep engagement with both antique sources and contemporary Venetian aesthetics.

3. Reliefs of Bacchus and Ariadne (c. 1505–10)

Among Tullio’s finest narrative works is the relief of Bacchus and Ariadne, now in the Ca’ d’Oro (Galleria Giorgio Franchetti) in Venice. This high-relief marble panel tells the mythological tale of Bacchus finding the abandoned Ariadne. The composition is flowing, romantic, and balanced, marked by finely carved drapery and emotive faces.

Such works show Tullio’s innovative handling of myth, where the gods are not distant entities but relatable figures imbued with grace and tenderness. The relief is as much a love poem in stone as it is a depiction of a myth.

4. The Young Couple (Busti di Giovane Coppia) (c. 1500)

This beautiful double bust, attributed to Tullio, portrays a young Venetian couple. It is a rare secular portrait in Renaissance sculpture and reveals the artist’s mastery of subtle emotional expression. The youthful beauty, downcast eyes, and serene facial features give the bust an almost dreamlike quality.

Now in the Musée du Louvre, this piece is a testament to the private and intimate side of Tullio’s genius.

How Did Tullio Lombardo Make His Sculptures?

Tullio Lombardo worked primarily in Carrara marble, one of the most esteemed materials of the Renaissance. His process began with detailed sketches and clay or wax models, often developed in his family workshop. As a trained architect, Tullio approached sculpture with a deep understanding of form, space, and proportion.

Here are some highlights of his sculpting methods:

Classical Study: Tullio was deeply inspired by Greco-Roman antiquities. Venice’s close ties with the Eastern Mediterranean allowed exposure to classical relics. He incorporated idealized forms, balanced compositions, and mythological themes.

Emotive Carving: One of his trademarks is the gentle modeling of faces. Rather than relying on harsh lines, Tullio used subtle chiseling techniques to create soft expressions and lifelike eyes, often slightly downcast or introspective.

High Reliefs and Bas-Reliefs: In his narrative panels, such as those of Bacchus and Ariadne, Tullio varied the depth of his carving to create illusionistic space. This use of perspective in relief sculpture was a Venetian innovation that Tullio helped refine.

Polishing and Surface Finish: After carving, the marble was polished to a high sheen using abrasives and cloths. This gave his sculptures an almost translucent skin-like quality, particularly in depictions of the nude.

Workshop Practice: As was common in Renaissance Italy, Tullio worked within a workshop system, often collaborating with his father and brother. However, his individual touch can be identified in the most refined and expressive sections of each piece.

Where Are Tullio Lombardo’s Sculptures Located?

Tullio Lombardo’s works are dispersed across major cultural institutions and churches, primarily in Italy but also internationally. Here are the main locations:

1. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

“Adam” (restored after a fall in 2002): One of the very few life-sized male nudes in marble from the Renaissance outside Italy.

2. Church of San Giovanni e Paolo, Venice

Monument of Doge Andrea Vendramin: An architectural and sculptural tour de force located in one of Venice’s most important churches.

3. Ca’ d’Oro (Galleria Giorgio Franchetti), Venice

Relief of Bacchus and Ariadne: A mythological masterpiece showing Tullio’s expertise in narrative sculpture.

4. Museo Correr, Venice

Various sculptures and busts attributed to the Lombardo workshop.

5. Musée du Louvre, Paris

The Young Couple: A moving example of Renaissance portraiture in marble.

6. Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice

Hosts several fragments and pieces attributed to the Lombardo family.

How Much Are Tullio Lombardo’s Sculptures Worth?

Because many of Tullio Lombardo’s works are enshrined in churches and public collections, they are not available for sale, and thus rarely have auction records or formal valuations. However, given their historical importance and rarity, experts estimate that if a verified Lombardo work were to appear at auction, it could be valued in the tens of millions of dollars.

To provide context:

Comparable Renaissance sculptures by less renowned artists have sold for $5–10 million.

A piece like “Adam”, due to its size, condition, and historical significance, would likely be valued upwards of $30–50 million, though it is considered priceless due to its rarity and provenance.

Institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of Art or the Louvre spend decades cultivating such acquisitions, often funded by major grants or donations. Tullio’s sculptures are seen not merely as decorative or collectible items but as cornerstones of Renaissance heritage.

Legacy of Tullio Lombardo

Tullio Lombardo may not be a household name today, but among scholars and art historians, he is revered as a poet in marble, a sculptor who captured the balance between body and soul, between antiquity and modernity. He elevated funerary art to high culture and gave mythological figures a pulse.

In a world where power and prestige often overshadow subtlety and grace, Tullio’s work invites us to pause, reflect, and admire the tender humanity beneath the marble surface. His genius lies not in grandiosity, but in serenity, in the contemplative tilt of a head, the loving gaze between mythic lovers, the soft curve of a shoulder.

As more of his lesser-known works are reexamined and attributed correctly, his influence in the sculptural lineage of the Renaissance becomes clearer. Without Tullio, the bridge between classical beauty and Renaissance humanism would have one less elegant arch.

If you ever find yourself wandering through the majestic churches of Venice, or the hallowed halls of the Met, take a moment before Tullio Lombardo’s work. You won’t just see a sculpture, you’ll see a soul, eternal in marble.