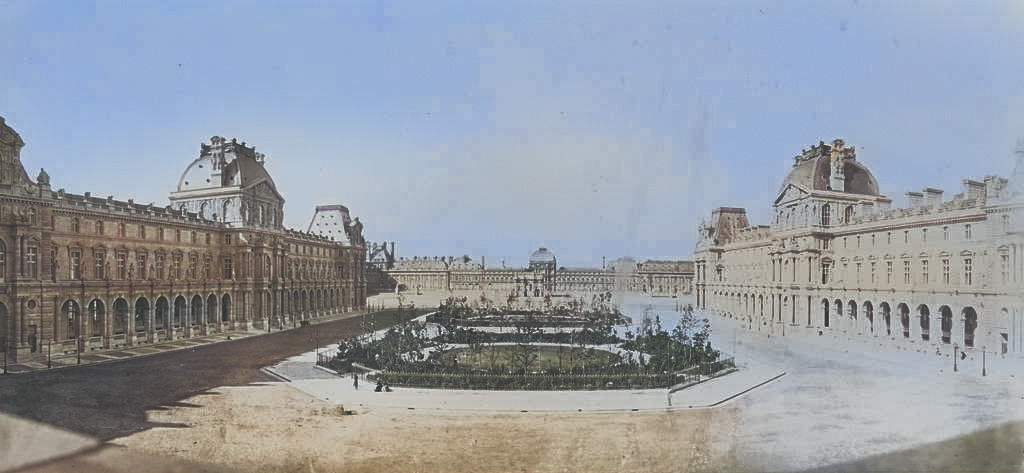

Who Lived in the Louvre Before It Was a Museum?

The Louvre, one of the most iconic landmarks in Paris and the world’s largest art museum, is renowned for its vast collection of masterpieces, including the Mona Lisa and the Venus de Milo. However, before it became a repository of art and culture, the Louvre was a structure with a rich and layered history, serving various roles over the centuries. To understand who lived in the Louvre before it was a museum, we must trace its transformation from a medieval fortress to a royal palace, and finally, to the cultural institution it is today. This journey involves exploring the lives of kings, queens, courtiers, and even soldiers who shaped its destiny.

The story of the Louvre begins in the late 12th century, during the reign of King Philippe Auguste (Philip II). Concerned about the potential for invasions along the Seine River, Philippe ordered the construction of a fortress on the site where the Louvre stands today. This early version of the Louvre, completed around 1202, was designed primarily as a military stronghold. It featured thick walls, a deep moat, and a massive cylindrical keep at its center, known as the “Grosse Tour.”

The occupants of this medieval Louvre were not kings and queens but soldiers and garrison commanders tasked with defending Paris. The fortress served as both a military base and a repository for the royal treasury. Its purpose was purely functional, and there is little evidence to suggest it was intended for luxurious living or artistic endeavors.

In the 14th century, under King Charles V, the Louvre began its transformation from a utilitarian fortress into a royal residence. Charles V, known for his intellectual pursuits and appreciation for art, decided to move the royal court to the Louvre. To make the structure suitable for habitation, he commissioned extensive renovations, including the addition of towers, private apartments, and lavishly decorated interiors.

The royal court’s relocation to the Louvre marked a significant shift in its function and inhabitants. Charles V and his queen, Jeanne de Bourbon, resided there, along with their courtiers, advisors, and servants. The palace became a hub of political activity, intellectual discourse, and artistic patronage. Charles V established one of the first royal libraries within the Louvre, setting a precedent for the site’s future association with culture and learning.

Following Charles V’s death, the Louvre’s status as a royal residence waned as subsequent kings preferred other palaces, such as the Château de Vincennes and the Palace of Fontainebleau. For much of the 15th and early 16th centuries, the Louvre fell into relative neglect, its grandeur diminished.

The fortunes of the Louvre changed dramatically during the French Renaissance, under the reigns of Francis I and his successors. Francis I, an ardent patron of the arts and an admirer of Italian culture, initiated a major reconstruction project to convert the medieval fortress into a magnificent Renaissance palace. The cylindrical keep and much of the original medieval structure were demolished to make way for elegant wings and courtyards.

Francis I’s court brought the Louvre back to life, filling its halls with artists, architects, and intellectuals. The king himself took up residence in the palace, along with his family and an entourage of nobles and servants. Francis also began the royal art collection that would eventually form the nucleus of the Louvre’s museum holdings. His acquisition of Leonardo da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa” during this period underscored his dedication to the arts.

Under subsequent monarchs like Henry II and Catherine de’ Medici, the Louvre continued to grow and evolve. Catherine, a queen consort and later regent, played a significant role in shaping the Louvre’s development. She commissioned the construction of the Tuileries Palace and Gardens, which were connected to the Louvre, creating a grand ensemble of royal architecture. During this era, the Louvre became not just a residence but a symbol of French royal power and cultural refinement.

The 17th century saw the rise of Louis XIV, the “Sun King,” who preferred the splendor of the Palace of Versailles over the Louvre. Although Louis XIV largely abandoned the Louvre as a primary residence, he did not neglect its importance as a center of art and administration. He commissioned several architectural projects, including the completion of the Cour Carrée and the addition of the iconic east façade, known as the “Colonnade” by Claude Perrault.

During Louis XIV’s reign, the Louvre housed not only government officials and artists but also a burgeoning collection of art and antiquities. These were stored in various rooms and galleries, accessible primarily to the royal family and their guests. The palace’s residents during this time included high-ranking courtiers, architects, and administrators involved in the king’s grand vision for Paris.

The French Revolution (1789-1799) marked a dramatic turning point in the history of the Louvre. With the fall of the monarchy, the Louvre’s royal residents were ousted, and the palace was repurposed for the people. In 1793, the National Assembly declared the Louvre a “museum for the nation,” officially opening the Muséum Central des Arts in the Grande Galerie.

While the museum’s establishment ended the era of royal habitation, it also symbolized a democratization of culture. The Louvre’s transformation into a public institution was driven by revolutionary ideals, with artworks and treasures seized from royal collections and aristocratic estates placed on display for citizens to enjoy.

The Louvre’s pre museum history is a tapestry woven with a diverse array of inhabitants. Initially, it was soldiers and commanders who lived within its medieval walls, protecting Paris from invaders. In the 14th century, it became a residence for Charles V and his court, bringing scholars, artists, and nobility into its orbit.

During the Renaissance, the Louvre flourished under the patronage of Francis I and subsequent monarchs, becoming home to not only royalty but also the artistic and intellectual elite of the era. Even as its role shifted in the 17th century, it housed government officials, architects, and courtiers who maintained the palace and contributed to its grandeur.

By the time of the French Revolution, the Louvre’s occupants had changed from kings and queens to administrators and curators tasked with overseeing its transformation into a museum. This evolution underscores the Louvre’s adaptability, reflecting the changing political and cultural landscape of France.

The Louvre’s history before it became a museum is a fascinating journey through medieval, Renaissance, and early modern France. From its origins as a fortress guarding the Seine to its rebirth as a Renaissance palace and its gradual transformation into a symbol of absolutist power, the Louvre has been shaped by the lives of those who inhabited it. Soldiers, monarchs, courtiers, artists, and intellectuals all left their mark, each contributing to its rich legacy.

Today, as millions of visitors walk through the Louvre’s galleries, they are not just admiring art but also stepping into a space imbued with centuries of history. The walls of the Louvre tell stories of defense, opulence, and revolution to the ever evolving role of this iconic structure in the heart of Paris.